Compromise is often seen as a silver bullet for the problems plaguing modern politics. If only our politicians were less confrontational and better at negotiating compromises, we are told, much of the rancor characterizing contemporary political discourse would disappear. For this reason, many observers on both left and right defend the filibuster, a Senate procedure that makes passage of a law not supported by a super-majority of senators impossible. By preventing the passage of partisan legislation and forcing senators from different parties to forge compromises, it is often argued, the American political system prevents radical ideas from being realized.

This argument, however, is flawed on several counts. It is true that we need to abstain from large-scale “social engineering” projects, as Karl Popper called them. But while the filibuster may be one means of preventing such projects from being implemented, it also prevents us from learning by facing the consequences of mistaken policies created by forced compromises, dilutes the responsibility of our political parties for the policies they champion, and blocks new initiatives. The world in which the US Senate has no filibuster may, to some degree, encourage “utopian social engineering” projects. Such projects, however, can be curtailed by other features of the constitutional system. In contrast, unless it is eliminated, the negative effects of the filibuster are likely to be with us as long as the Senate itself.

It is of course possible to imagine the advantages of a political system in which key political players craft rational policies based on the best social science instead of stonewalling and strangling each other’s partisan initiatives. Still, that is not the hyper- partisan, polarized political world we live in 2022 or can hope to escape in the near future. Given our political realities, we are better served by confronting the negative implications of the political compromises forced by the filibuster. Such compromises prevent us from benefiting from one of the most outstanding features of free and open societies, namely the process in which we face the consequences of targeted and even partisan policies and learn by trial and error. By forcing compromises and diluting the ideas underlying partisan policy proposals, the filibuster obfuscates and complicates the policy making process and keeps us from detecting and eliminating ineffective policies. Put more concisely, the filibuster allows a minority of senators to put a stop to the rational process of testing our ideas. As Alexander Hamilton wrote of super-majorities in Federalist No.22:

The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. But its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of the government, and to substitute the pleasure, caprice, or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent, or corrupt junto, to the regular deliberations and decisions of a respectable majority.

Fortunately, there is a way to advance a truly rational and scientific political process based on what Karl Popper called “piecemeal social engineering.” Enacting policies limited in their scope and impact makes it possible to estimate their consequences and learn from mistakes more precisely. Discerning chains of causation becomes difficult when compromised policies are passed and unintended, rather than planned, effects shape the social environment. In the sciences, we make predictions based on theories, and if subsequent observations refute the predictions made by our original hypotheses, then we can safely eliminate them. When policy changes are at once seismic and unintended, however, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to forecast their implications. At this point, the scientific process of policy making breaks down. The evolutionary process of the selection of ideas cannot function properly when their reflections in actual policies become so entangled that cause-and-effect relations become blurred.

Consider the value of recent state-level debates over marijuana policy. Studying the effects of marijuana legalization on teenage consumption of drugs across the entire United States is less likely to yield noticeable increases in our knowledge than researching this phenomenon in, say, Oregon. Studies that attempt to measure the effects of marijuana policy across the whole United States cannot hope to capture the sheer complexity of social conditions underlying consumption of drugs by young adults in a country as vast and diverse as the US. In each part of the country, unique circumstances specific to that region affect what must be taken into consideration in judging the impact of policies and making adjustments based on what we have learned. Lessons we draw from statistics on the national level cannot be applied to particular localities without significantly distorting the real situation in those areas.

Moreover, when a policy is the result of political accommodation, reward for success as well as responsibility for failure become hard to ascertain. As David Deutsch writes in The Beginning of Infinity, “The key defect of compromise policies is that when one of them is implemented and fails, no one learns anything because no one ever agrees with it.” Good ideas, when mixed with bad ideas (and vice-versa), cannot be tested, making it difficult to learn from our successes and failures. Instead, erroneous explanations are proposed for good policies and impede our understanding of why they worked. Conversely, erroneous explanations are given for why failed policies failed.

For example, compromise economic packages adopted in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis left the underlying theoretical issues unresolved: Democrats argued that post-2008 growth was slow because spending was too low, blaming Republican stubbornness; Republicans held that Democratic profligacy was behind America’s economic under-performance in the early 2010s. In contrast, when the Keynesian economic paradigm, following decades of unchallenged dominance in American economic thinking since the Great Depression, failed to cope with the 1970s stagflation, it was discarded by many mainstream policymakers and academics, paving the way for the rise of neoclassical economics. In this instance at least, a clear failure in the ability of a dominant theory to explain a particular phenomenon (stagflation) led to an alternative explanation and new policy recommendations. Today, paradoxically, if the Democrats and the Biden administration manage to pass their own reconciliation economic package without support from the GOP, it could actually increase our understanding of which economic paradigm best explains how our economy works, and which does not. Unhindered by Republican budget hawks, Biden’s economic policies could boost America’s economic growth without dramatic increases in inflation — or they may not. Either way, there is a gain in knowledge of what works and what does not.

It should also be noted, however, that allowing a party to freely exercise its vision does not imply that it should be able to pursue any policies it wants. As noted earlier, it is difficult, if not impossible, to learn from what Karl Popper defined as holistic experiments, or large-scale policy changes. Put bluntly, “it is very hard to learn from very big mistakes.” As Popper also put it in The Poverty of Historicism, “This [kind of] experiment does not help us to attribute particular results to particular measures; all we can do is to attribute the ‘whole result’ to it; and whatever this may mean, it is certainly difficult to assess.”

Here the value of constitutional checks and balances becomes evident. They limit the scope of policy changes and thereby put constraints on the central government’s ability to impose untested policies that promise novel, wholesale changes onto American citizens. Making small errors and learning from them is how society attains progress, while pursuing utopian social engineering projects with no opportunity to scientifically analyze their consequences has been, historically, a recipe for disaster. More concretely, what this means is that we can have limited government without the filibuster, but with it our politics cannot be rational or rooted in the use of trial and error to learn from our mistake.

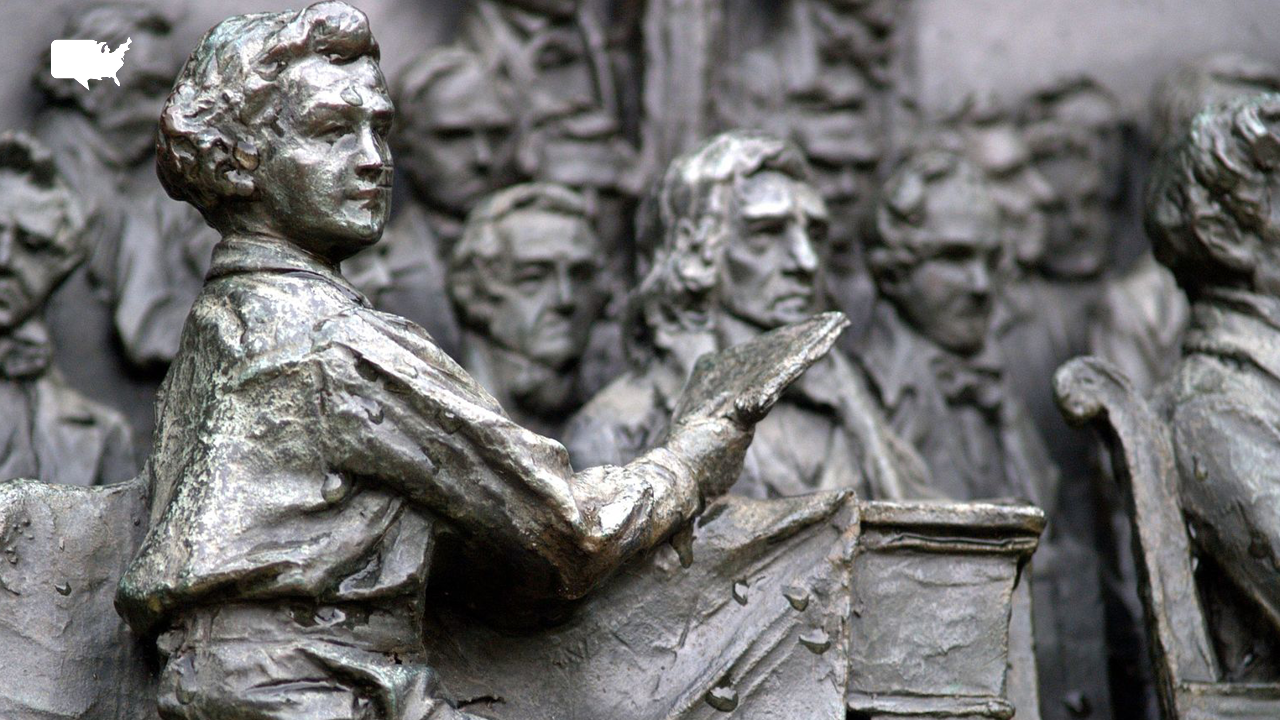

If all of this is not enough, it should also be noted that the Framers did not, in fact, establish the filibuster as an element of America’s system of checks and balances in the first place. Why add a check that was never intended and prevents us, ultimately, from pursing a rational policy process? The US Constitution delineates all cases in which a super-majority of votes is required (e.g. to impeach a government official or override the president’s veto), and “these textual requirements suggest the framers envisioned that majority rule would be the norm, except where otherwise provided,” according to Catherine Fisk, professor at the University of California, Berkeley. The Senate already prevents the tyranny of the majority by virtue of its uneven distribution of power among states with different populations, just as the Founding Fathers intended. Filibuster, however, arose as an accidental by-product of the Senate’s internal procedural dynamics: Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina saw in the absence of motion to end debates a loophole that would allow these “debates” to proceed indefinitely. Over time, using filibusters to stonewall the majority’s initiatives became a common practice. In the last two decades, this has grown to the point where neither party can effectively set forth its preferred ideas and policies for shaping public policy. As The Economist puts it, “The men who framed America’s constitution intended the Senate as a bulwark against the tyranny of the majority. Its present-day failure to pass bills supported by a majority of its members, though, was never any part of that original design. It is the result of what seems to have been a genuine error: a lack of fixed procedures for shutting down debate.”

Jettisoning ideas that fail to accurately represent reality, and replacing them with new ones, is critical to attaining progress in politics. The filibuster prevents new ideas from being tested, hindering the evolutionary mechanism underlying human progress. Thomas Jefferson once wrote, referring to the Missouri compromise, that “it is hushed, indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence.” There are situations in which compromise is desirable; however, we need to stop seeking political compromise for its own sake. Compromises should be neither discouraged nor be the primary goal of politics. We should let the underlying political forces operate rather than conceal them, in order to allow us to learn from mistakes and expand our knowledge. Together, a scientific approach to politics and policy analysis based upon Popper’s “piecemeal” approach to social engineering and a correct understanding the original contours of our system of checks and balances allows us to steer between the Scylla of policies designed to create utopian social change and the Charybdis of a policy system in which the filibuster makes it impossible for us to understand why some public policies worked and others did not.

Sukhayl Niyazov is an independent writer. His work has appeared in The National Interest, City Journal, Foundation for Economic Education, Law and Liberty, and other publications.