One of the most widely criticized elements of America’s political system is its winner-take-all, first-past-the-post principle that leads to the domination of two political parties. “The Two-Party System Broke the Constitution,” writes The Atlantic. Foreign Policy argues that “the only way to prevent America’s two-party system from succumbing to extremism is to scrap it altogether.”

The desire to abandon plurality voting—where the winner is whomever gets the largest number of votes in a particular district or state—in favor of proportional representation has become increasingly popular, especially in the wake of the 2016 presidential election, as many voters on both left and right were dissatisfied with their respective parties’ presidential nominees. For example, a 2017 Gallup poll found that a record-high 61% of respondents wanted a third-party option.

For all the flaws of the single-member majority elections, however, the two-party system is still preferable to proportional representation. It is best equipped for what Karl Popper once defined as the purpose of democracy: the removal of bad leaders without violence and the trial and correction of policy errors.

When there are only two parties, if voters are dissatisfied with how the party in power governs, they can vote it out in the next election. But in a system with proportional representation, even if a party in power is thrown out from government by a majority of citizens in the next election, it could still cling to power by forming a coalition with a smaller party. Unlike other alternatives, the two-party system makes it possible for voters to signal their views as to the effectiveness and desirability of the government’s policies.

The Tyranny of the Minority

Philosophers have long debated which form of government is the best. But these abstractions ignore the fact that a perfect society can never be created by fallible people. As Alexander Hamilton remarked, “I never expect a perfect work from an imperfect man.” To paraphrase James Madison, men are not angels, and that’s why government is necessary. We need the kind of government that would constrain the negative elements of human nature and solve problems rather than one that tries to establish a utopia.

America was therefore not an attempt to create the best form of government, but rather the best possible—a political system theoretically capable of solving concrete social problems, eliminating policy errors and learning from them. The hallmark of every rational system should be the ability of voters to dispose of ineffective government and by extension policies, peacefully. This was how Karl Popper defined democracy — a system that provides peaceful means of removing bad leadership.

In his 1988 article for The Economist, Karl Popper explained why this theory of democracy necessitated a two-party system. The old theory —that democracy is the rule of the people — meant that the government should represent the people, meaning that proportional representation is necessary, so that “the numerical distribution of opinion among the representatives mirrors as closely as possible that which prevails among those who are the real source of legitimate power: the people themselves.”

The multi-party democracy that results from proportional representation is hailed as its main advantage over plurality voting; after all, the will of the people is best reflected under such an arrangement. But the increase in the number of parties makes it much more difficult for voters to remove bad leaders and punish them for bad policies, potentially leading to a tyranny of the minority, where the third-largest parties exert disproportionate influence. The third-largest party’s policies may not even reflect what voters want.

Winner-take-all principle-based electoral systems, however, dilute the influence of third-largest political parties and place limits on the potential tyranny of the minority while making it easier for voters to signal their attitudes towards the policies pursued by two parties.

In an electoral system with proportional voting, no party usually receives the majority of votes, and, in most cases, the leader of the third-largest party decides to join one of the two largest ones to form a government coalition. Ironically, a system that is supposed to allocate influence to a party based on the number of votes it receives gives a disproportionate amount of power to the third-largest parties.

Germany’s Free Democratic Party, for instance, which, from 1949 to 1988, was the third-largest party in the country, despite never receiving more than 12.8 percent of the vote, decided which of the two largest parties would govern (choosing three times to put the less popular of the two into power).

As David Deutsch writes, in a proportional system, what counts most is not the changes in public opinion but “changes in the opinion of the leader of the third-largest party. This shields not only that leader but most of the incumbent politicians and policies from being removed from power through voting.” In a system with proportional representation, it is often difficult to get rid of incompetent governments, even if a majority of citizens do not support them. Unpopular parties can form coalitions with other parties to stay in power.

It is thus difficult to hold a single party responsible in a governing coalition; in a two-party system, by contrast, citizens can more easily hold the government accountable because voters can clearly signal their attitudes by simply voting the dominant party out. The new government will implement new policies, whose effects will be analyzed and criticized. If their policies have socially beneficial consequences, then the government will most likely be rewarded by voters in the next election. If not, then the government will be voted out, since the public will have had time to assess which kinds of policies do not work and should therefore not be enacted.

Correcting Errors

Historically, new U.S. presidents have entered the White House with majorities in both houses of Congress. Presidents are essentially given an electoral mandate for the next two years and an opportunity to demonstrate their administration’s abilities. Should they fail, their party will be defeated in the midterm elections, typically by losing a majority in the House of Representatives.

Plurality voting does not only prevent a bad president from implementing unpopular policies but also allows changes in public opinion to influence the workings of the government for the next two years, as it is forced to forge compromises with the opposition, after being seen by voters as incapable of implementing good policies on its own. This happened, most recently, after both Obama’s landslide victory in 2008 and the full Republican control of the government in 2016: in each case, the incumbents gradually lost their majorities, popular mandate, and ability to exercise policy without constraint, relatively speaking.

Likewise, the 2020 election did not produce a landslide victory many Democrats expected. Democrats actually lost seats in the House of Representatives and only narrowly took over the Senate — mostly as a result of a series of blunders by Republicans and Donald Trump in Georgia following the November election. Voters made clear both their aversion to Trumpism as well as the wariness of the unchecked Democratic government — something that, hopefully, both parties will take into consideration when preparing for the next elections.

The two-party system is far from perfect, and the contemporary American political system needs substantial reforms to address issues like centralization of power in the hands of the president, gridlock and stonewalling in the Congress, partisanship, gerrymandering, and party leaderships’ inordinate influence on legislators, among others. But to blame all of the problems America faces, from political polarization and partisanship to low voter turnout and dissatisfaction with the government, just on the two-party system is to ignore the complexity of society, as societal phenomena often have multiple causes and effects and hidden interconnections.

Addressing these challenges requires implementing separate, piecemeal solutions rather than overhauling the entire system of governance; piecemeal reforms can fail, and we should learn from our mistakes — something that is impossible when big changes are made since this makes it very difficult to analyze the causes and effects of particular policies when they all become entangled with each other.

The essential feature of a free and open society is implementation of new ideas in practice and learning from mistaken policies, effective communication and incorporation of voters’ opinions by politicians, and, most importantly, removal of bad leadership without violence — something that the two-party system, for all its limitations, is best (most consistently) capable of achieving.

Sukhayl Niyazov is an independent writer. His work has appeared in The National Interest, City Journal, Foundation for Economic Education, Law and Liberty, and other publications.

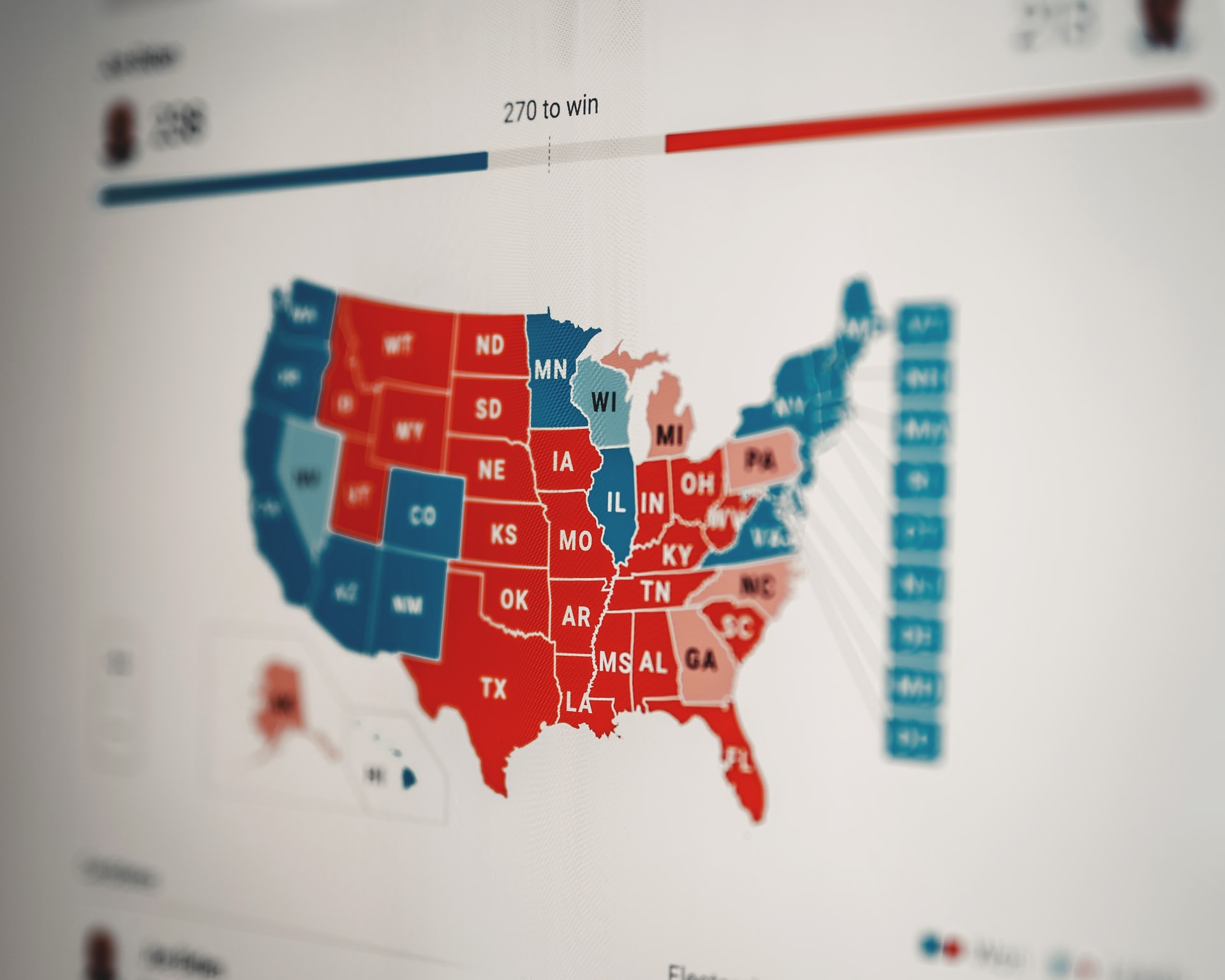

Cover Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash.