Ross Douthat wrote a May 27 column for The New York Times provocatively titled, Free Speech Will Not Save Us. The columnist was casting doubt on the argument that the best way to cure political polarization is with renewed respect for the right of people to speak.

Douthat is correct that the right of free speech is imperiled today. NFL owners are willing to silence the speech of their players for fear of fan backlash. Students shout-down right-wing speakers on campus. What Douthat added that is new, is that the polarization that besets America today would only be worsened by greater respect for free speech. We would have only more divisive speech. The same may be said about calls for greater democracy or more transparent government.

WHEN PEOPLE HATE AND DISTRUST EACH OTHER, APPEALS TO REASONABLENESS, THE COMMON GOOD, AND OPENNESS ARE IRRELEVANT.

What is required to heal America is a return not to free speech, but to the original assumption behind free speech. The traditional reason that we protect even outrageous messages from government interference is the expectation that out of this cacophony of messages, truth will emerge. Free speech is not just about speaking, but about listening and deciding.

It is this expectation of the emergence of truth that leads the authors of my Constitutional Law textbook to include a quote in the free speech material from John Milton’s Areopagitica: “And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?”

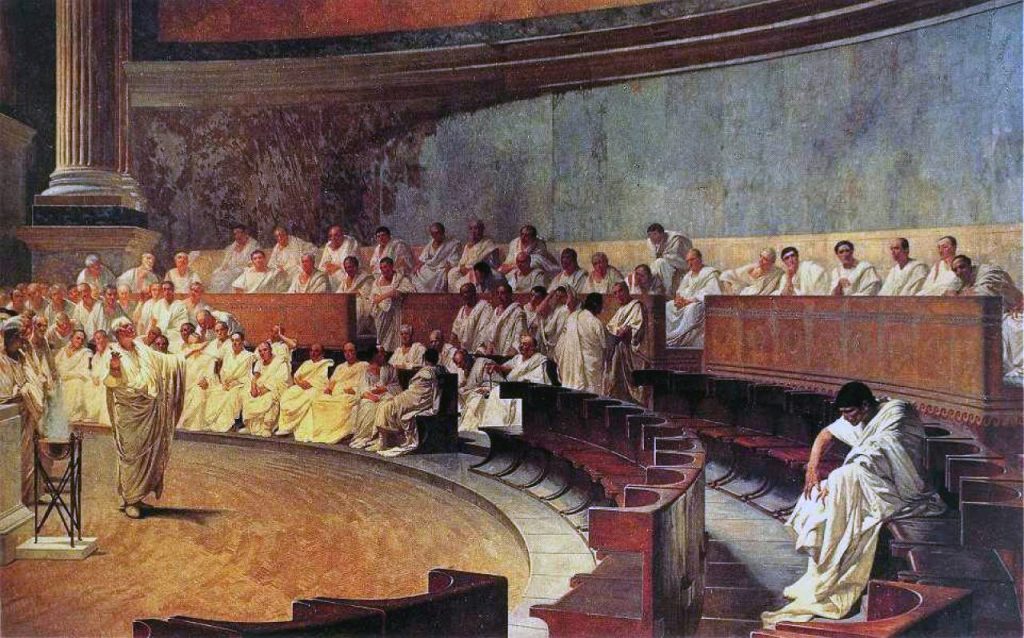

Free speech can thus be thought of, as it might have been thought of by Milton, as an echo of the view of Gamaliel in the Book of Acts. In that story, the Apostles are arrested and brought before the Sanhedrin, where they are to be punished, perhaps killed. Gamaliel, identified as a Pharisee, warns the elders that they should be careful. If the cause of the followers of Jesus is not from God, then their efforts, like those of prior, false Messiahs, will come to nothing. But if their cause is from God, to oppose it would be to fight against God.

In terms of the role of free speech, the point of the Gamaliel story is not theistic or religious. The point is about truth. If the message of the followers of Jesus is not true, it will fade away, as the story of prior would-be Messiahs had done. No action against the speech of the Jesus followers is needed. But if their message is true, then it should not be suppressed. In modern terms, Gamaliel was telling the Sanhedrin to let the marketplace of ideas work.

The Gamaliel story illustrates what happens to political divisions when it is assumed that unfettered speech leads to truth. Gamaliel was asking the political leaders of his time to reconsider their hatreds. Since there is an objective standard of truth and justice in reality, our responsibility is to conform with it. Thus, we must treat even our perceived enemies as potential sources of wisdom. We need not fear them. If they are not in the truth, their efforts will fail. It may be, however, that they are right. If so, eventually the truth will be known.

THE MAIN ACTIVITY OF POLITICAL LIFE, THEREFORE, IS LEARNING THE TRUTH ABOUT THE UNIVERSE.

We can now rephrase Douthat’s insight. More openness to free speech will not save a society unless that society accepts the assumption behind the commitment to free speech—agrees that there are objective standards of right and wrong, of true and false, and that open exchanges lead to their recognition. Not just factual truth. This expectation must also include what might be called moral truth.

Unfortunately, we no longer hold this view. In the first place, we are uncomfortable with the concept of truth itself. The assertion that there is a truth of things that can be known, and that some perspectives are closer to that truth than other perspectives, strikes us as privileging. Such privileging is often criticized as sexist, racist, proto-colonial or more generally as “essentialist.”

As the memoirist Mary Karr puts it, any claim of truth today must come “with quotes around it.” It is just too presumptuous to claim to know the truth.

Then there is the question whether the universe has any kind of order or point. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., famously stated that “…the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But we are now more likely to believe the universe is an indifferent collection of blind forces that, in the words of a recent New York Times headline, Doesn’t Care About Your Purpose. Reality is just a play of accident and contingency.

It follows that there are no objective moral standards. Every society has its own cultural commitments. Each person has her own beliefs. Value is subjective. Humans make their own meaning.

In other words, history cannot be thought to move toward justice both because there is no overall movement in history and there is no such thing as justice.

THE ASSUMPTION THAT FREE SPEECH LEADS TO TRUTH REQUIRES A HIGH REGARD FOR THE CAPABILITIES OF ORDINARY PEOPLE.

It has to be thought that people will recognize the truth when it is offered. Today, we don’t believe that either. We believe instead in the power of Big Money to fool people. We believe the human brain is inadequately wired to discern truth—that it remembers falsehood as true if the falsehood is repeated often enough.

Naturally, believing that people lack the capacity to discern truth means that we have no respect for the people who disagree with us. There is no point in trying to convince them of anything. They will not be reasonable. They are not worth our time.

We know what many Republicans think of Democratic voters from a pirated response from Mitt Romney during the 2012 Presidential campaign:

“There are 47 percent of the people who will vote for the president no matter what. All right, there are 47 percent who are with him, who are dependent upon government, who believe that they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to care for them, who believe that they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it. That that’s an entitlement. And the government should give it to them. And they will vote for this president no matter what…These are people who pay no income tax.”

Nor can there be any doubt what Democrats think of Trump supporters. Hillary Clinton’s famous deplorables quote has a kind of eerie parallelism to Romney’s words:

“You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump’s supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right? The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic — you name it. And unfortunately there are people like that. And he has lifted them up. He has given voice to their websites that used to only have 11,000 people — now 11 million. He tweets and retweets their offensive hateful mean-spirited rhetoric. Now, some of those folks — they are irredeemable, but thankfully they are not America.”

Our political campaigns perfectly reflect these views. We no longer even try to convince anyone of anything. We simply attempt to win the turnout battle by relying on our base.

We therefore have to shout-down the racist so his message does not get out and convince people. With our current assumptions, free speech is a mistake. This society can be saved only if the original assumption behind free speech is correct and our current views are false.

What ails America has nothing to do with Donald Trump and his lies. It has nothing to do with Hillary Clinton’s emails and her lies.

THIS SOCIETY NEEDS TO HAVE A DEBATE ABOUT THE DEEPEST ISSUES OF ONTOLOGY. WHAT IS REALITY ACTUALLY LIKE?

The theologian Bernard Lonergan put the fundamental question as follows: “Is the universe on our side?” The recent growth of materialism, relativism and nihilism has not occurred out of careful reflection. The decline has come about mostly as a lazy habit of thought. We just assume that Dr. King was wrong—that he was naïve to think that the universe bends toward justice.

But was he? As a strictly empirical matter, hasn’t history moved over time, though admittedly not in a straight line, in the direction of greater justice? Do not the great movements of reform—from the abolition of slavery, to the establishment of robust international norms, to the growing recognition of the rights of women, and many other instances, bespeak a kind of moral progress? And aren’t these changes effectively irreversible? How did an indifferent universe end up with such a history?

This empirical question is the starting point for rehabilitating Dr. King’s view. Think about history as a whole. In the past centuries, humanity has moved into a period of unparalleled prosperity, security and peace. Advances in medicine, knowledge and technology have greatly increased human welfare world-wide. Far from the clash of civilizations, we know more about, and respect each other, to a greater extent than ever before in human history.

We have moved out of warrior culture into an era of human rights in which the most vulnerable populations—women, the disabled, the poor and others—are no longer entirely at the mercy of the powerful. Human sacrifice, slavery and caste are now either unknown or mere shadows of their former, sinister presence. And all of this has led to the establishment of constitutional democracy, now so dominant a system that even its detractors find it necessary to falsely claim to follow it.

Of course, Dr. King acknowledged the long and merely bending movement of justice. It is the case that new forms of human trafficking exist and that the 20th Century was the bloodiest in history.

But crime is not the same as system. Victims today can obtain freedom and protection, whereas in previous eras, organized society accepted these practices as normal. And the brutality of conflict in the 20th Century was a result of increased human capacity for killing. That material increase is not a reversal in the arc of the moral universe.

This empirical claim is a first step. Statements like The Universe Doesn’t Care About Your Purpose are really faith claims rather than well-considered arguments. They have been rendered plausible by the death of the supernatural God. But, perhaps, we have just been unimaginative as to what a purposeful universe looks like and what its foundations might be. The first thing we have to do is consider the possibility that Dr. King might have been right.

Eventually Albert Camus, formerly accepting nihilism, decided that he had been wrong. This is what he said at a gathering with Koestler, Sartre, Malraux, and Manès Sperber:

“Don’t you believe we are all responsible for the absence of values? And that if all of us who come from Nietzscheism, from nihilism, or from historical realism said in public that we were wrong and that there are moral values and that in the future we shall do the necessary to establish and illustrate them, don’t you believe that would be the beginning of a hope?”

Establish here does not mean create, but enable. Camus’s newfound faith is the only kind of hope that can save us. There are moral values. They do have power over time to be accepted. We do not have to silence our enemies, but enlighten them. We can have faith in the power of truth to convince.

As Gamaliel knew, only then can a society overcome its divisions. Only then can we recover a First Amendment worth having and a political life worth living.

Bruce Ledewitz is Professor of Law at the Duquesne School of Law. He is the author, most recently, of Church, State, and the Crisis in American Secularism (Indiana University Press, 2011).