As Americans prepare to head into one of the most contentious presidential election seasons in recent history, experts are looking 200 years into the past to the heated election between John Q. Adams and Andrew Jackson for insight and answers as to what may lie ahead. Several important questions concerning the similarity of the election and our present political climate are immediately evident. Can the election of 1824, similar in many respects to the upcoming election, repeat itself? Could presidential candidates in 2024 fail to win the majority of the Electoral College? And if so, would the 1824 precedence of the House of Representatives electing a president be instructive today? One cannot discount the possibility, especially if a third party and its candidate could draw electoral support to repeat this eventuality of no candidate winning the majority of the Electoral College. What happened in 1824 has not happened since. Exactly two hundred years ago, multiple candidates vied for the presidential seat and, as the campaign progressed, the field narrowed to four: Andrew Jackson, the hero of New Orleans and recent senator from Tennessee; John Q. Adams, the outgoing Secretary of State under James Monroe; William H. Crawford, a former Treasury Secretary (and presidential candidate a few years prior); and Henry Clay, the powerful Speaker of the House.

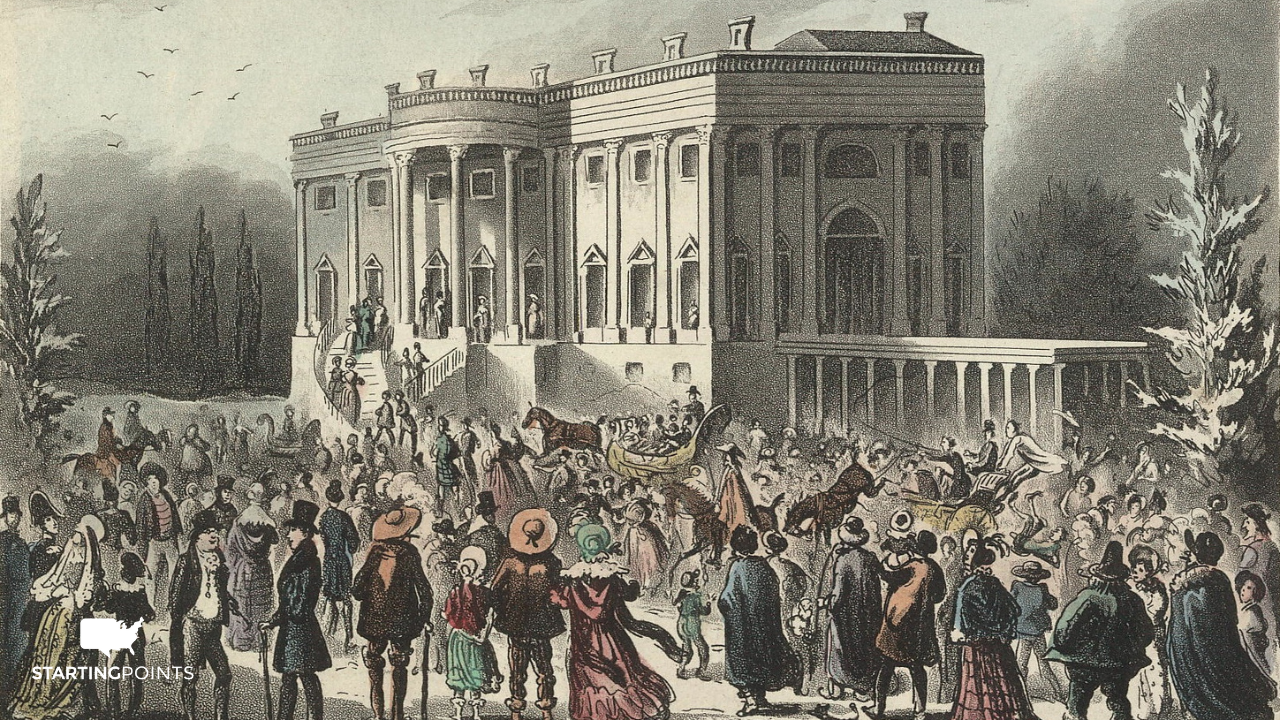

The Monroe “era of good feeling,” distinct for having no serious partisan divide, gave way to a presidential election that centered more on personalities than issues. Though there were several issues of contention, they were not, strictly speaking, partisan. One key issue in the campaign was political corruption: a call for leaders possessing character and ethics followed. Indeed, the election of 1824 is considered the first to tap into popular vote and with it an emphasis on personality and character. The election results had Andrew Jackson receiving the largest percentage of the popular vote as well as a plurality of the Electoral College. John Q. Adams came second in both, William H. Crawford was a distant third and Henry Clay, last. No candidate received the necessary majority of the Electoral College as required by the Constitution for appointment to the presidency.

Absent a majority of the Electoral College, the presidential election turned to the House of Representatives. Per the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, only the top three candidates were to be brought before the House of Representatives, where each state had one vote on the matter. This stipulation left the last candidate, Henry Clay, out of presidential consideration. However, due to his position as the Speaker of the House, he had the opportunity to use his vast influence and parliamentary expertise to direct the election as he wished. Denied the presidency, he maneuvered for the steppingstone position of Secretary of State (just as John Q. Adams, James Monroe, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson had done in earlier administrations). Clay figured that becoming Secretary of State would propel him to the presidency in the near future.

The key issue for Clay was how to become Secretary of State to the president of his choice. He could serve under John Q. Adams, but likely not under Andrew Jackson, whom he despised and feared. When counting states who would vote for the presidential candidate, Jackson would have likely received more states than any other candidate. With twenty-four states in the Union, the magic number was thirteen. Clay’s preference was John Q. Adams, but with Jackson initially securing 99 electors and Adams 84 (Crawford a distant third), the task of electing Adams in the House was daunting. The situation was further complicated by Clay’s own state, Kentucky, which instructed its congressional delegation to vote for Jackson in case Clay did not make it to the House of Representatives in the presidential election. In secret negotiations with Adams during late 1824 and early 1825, Clay promised that the three states that supported him (his state as well as Ohio and Missouri) would go for Adams in exchange for becoming Adams’ Secretary of State. In securing the needed states for Adams and putting him on top, Clay blatantly ignored his state’s instruction and as Speaker of the House and the head of his state’s delegation, he voted for Adams. John Q. Adams secured the needed majority of 13 votes to Jackson’s 7, becoming the Sixth President of the United States. Henry Clay became Secretary of State, hoping to secure his future presidential prospects.

The quid pro quo between Adams and Clay was quickly exposed by supporters of Jackson, crying foul as their candidate, who won the popular vote and the initial plurality of the Electoral College, was denied the presidential seat. Jackson became suspicious of an underhanded move when a young congressman, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, approached him late in December 1824 and suggested a bargain whereby he would win the presidency with Clay’s states if he appointed Clay Secretary of State, a likely move meant to put pressure on Adams who was initially hesitant to accept the bargain. Jackson, who could not believe this underhanded offer, angrily rebuffed Buchanan’s overture.

Once Clay was appointed Secretary of State and Jackson’s assumption about a corrupt arrangement proved plausible, Jackson began to talk about a corrupt bargain in the recent presidential election. The “corrupt bargain” branding stuck and spread quickly and with it the perception that Jackson was denied his presidency due to corrupt machinations. The Adams-Clay administration could not extricate itself from the lingering charge of corruption and with it the perception that this was not a fully legitimate election. As a counterattack to the charges of corruption, Jackson was nominated president in early 1825, some three and half years prior to the 1828 election. This slight was not lost on the Adams’ White House which found its single term rather constrained.

Significant political change took place between 1824 and 1828 due to several factors: the expansion of the country, the significant increase in the number of voters (men only) brought in part by the entry of eligible voters who did not necessarily own land, the end of the congressional caucus system, and the demise of the Federalist Party. The creation of the Democratic Party that formed around the figure of Andrew Jackson around 1826-27 was directly related to the corrupt 1824 election. The need to reduce the number of presidential candidates was clear to many who felt driven to prevent a situation where presidential elections would be sent to the House of Representatives. The promotion of partisan politics was thus taken as a necessary development whereby political issues were to be debated and argued and for that to take place, a viable party system was essential to a striving democracy.

Now, exactly two hundred years later, is it possible that we could witness another presidential election sent to the House of Representatives? Third party competition, similar to the 1824 period, is still present, but recent decades have given us no presidential election in which a candidate lacked the majority of electoral votes necessary to take office. One potential reason for the stability of more recent elections could be the relatively small level of popularity these third parties have garnered, but that doesn’t explain everything. Even the more significant third party of Ross Perot that yielded some 19 percent of the popular vote in 1992 did not disrupt the electoral majority, though it probably weakened George H. W. Bush’s candidacy and gave the win to Bill Clinton. What is more likely, but not directly relevant to the case here, is that a candidate may win the majority of the Electoral College without winning the popular vote. This, ultimately, was the case with the Hillary Clinton-Donald Trump election of 2016, and the Samuel J. Tilden-Rutherford Hays election in 1876.

Could a third party in 2024, then, be strong enough to prevent an electoral majority? The possibility of a third-party candidate yielding electoral votes is possible only if the said candidate wins a state-wide election, no doubt a daunting, but not impossible, task. Adding to the potential for third parties to reach such heights is the notion of “double haters,” the many voters who do not wish to see either Joe Biden or Donald Trump become president. These voters “hate” both and may vote for an alternative if presented one. Third-party candidates such as Robert F. Kennedy Jr. or Cornel West could prevent any candidate from winning the majority of the Electoral College. And if it does, what would happen then?

The critical question, then, is which candidate has the best chance of generating the support of 26 states, the necessary number of states to yield a simple majority in the House. Although counting states that are solidly Democratic and Republican can provide a general sense of the partisan divide in the House, swing states can add a measure of uncertainty to the situation. Moreover, though a state may be designated as Republican or Democratic, it does not necessarily correspond to a legislative direction. A better gauge, in my view, is to account for the following variables: A state governor’s party affiliation, a state Senate majority, a state House majority, and the partisan breakdown of a state’s House of Representative delegation. These variables are essential given the fact that the state assemblies are the principal decision makers in instructing its delegation on how to vote in the U.S. House of Representatives. Yet even here uncertainties are quite possible given the reality that states’ assemblies are divided, and different parties could occupy positions of governor, state assemblies, U.S. senators and House representatives (there are several states with unique settings between the two parties and one state, Nebraska, has only one legislative house). How, then, would a consensus about a given candidate be reached by each state?

Despite the caveat about states’ uncertainties, there are instructive facts. There are currently 27 Republican governors and 23 Democratic governors (excluding territories); there are 29 states with Republican senate majorities and 19 states with Democratic senate majorities (the remaining states have unique coalitional structure); and there are 28 states with Republican House majorities and 21 states with Democratic House majorities. If a House of Representatives delegation would rely on its internal vote and not on its state instruction, current partisan breakdown has 26 House delegations with a Republican majority and 23 House delegations with Democrats in the majority. One state has an equal number of Democrats and Republicans members of the House of Representatives.

With Republicans taking the lead in each of these variables, it stands to reason that if the presidential election turns to the House of Representatives that a Republican candidate would win. Yet, it is an open question whether states even have procedures for instructing their House delegation over voting on a presidential candidate? After all, no such vote was needed in the past two hundred years. Though the Constitution is clear about the House of Representatives deciding a presidential election when no candidate wins the majority of the Electoral College, it will be left to the states to manage the procedures that would give clear instructions to its congressional delegation.

And if the case of Henry Clay ignoring his state’s instruction, due to his own presidential ambition, is of any importance, his numerous presidential campaigns (1832, 1840, 1844, and 1848) would all go down in defeat with the charge of “corrupt bargain” hunting him for the rest of his political life. Even secondary individuals involved in the political bargaining in 1824 would have to answer for their role in the said election, decades later, as was the case of James Buchanan who was reminded of his role in that infamous election as late as 1856, when he ran for the presidency.

States will be involved when a presidential election turns to the House of Representatives due to lack of electoral majority. It is, therefore, incumbent upon them to issue clear instructions about their preference, and it is essential that each state’s delegation to the House follows the instruction of its state. Lacking clear instruction, a House delegation should proceed with its single vote in the most transparent way. Any deviation from this principle would bring charges of corruption in the House and tarnish the individual elected president, thus making for a difficult term in office.

Following the first few decades of the Republic, when partisan politics was not clearly spelled out and sometimes not even preferred, two presidential elections, in 1800-1 and 1824-5, were brought to the House of Representatives. It was clear to many then that a party system was essential to the nation, and that in substance and in structure, a contrasting ideological system would greatly benefit a democracy. This change that coalesced around Andrew Jackson, came about over the “corrupt bargain” of 1824. Clay, who was the culprit in that election, tried to shore up support in the House defending himself, but in the end, a congressional committee found his actions questionable. The findings, however, were only a slap on the wrist. More damaging was the public perception of a corrupt election and a very weak administration.

Our contemporary presidential election is similarly under stress and though it is not clear if another election would be decided by the House of Representatives, it is essential for the stability of the process that the constitutional provisions of a presidential election lacking a majority of the Electoral College would be above board and, hence, credible. Much pressure would land on the shoulders of the Speaker of the House who would have to ensure that the single vote of each state is executed properly before adjudicating the final election results.

Amos Kiewe, Ph.D., is Professor Emeritus of Communication and Rhetorical Studies at Syracuse University. His publications include several books, among them, Andrew Jackson: Rhetorical Portrayal of Presidential Leadership (2019, University of Tennessee Press), The Effects of Rhetoric and the Rhetoric of Effects: Past, Present, Future (University of South Carolina Press, 2015), FDR’s First Fireside Chat: Public Confidence and the Banking Crisis (Texas A&M University Press, 2007), FDR’s Body Politics: The Rhetoric of Disability (Texas A&M University Press, 2003), as well as editing a volume on The Modern Presidency and Crisis Rhetoric (Praeger, 1994). The article in this journal is based in part on his latest book, The Rhetoric of “Corrupt Bargain” in the 1824 Election (Lexington Books, 2022), which explores the intricacies of a presidential election decided by the House of Representatives when no candidate won the majority of the Electoral College and potential ramification for the current presidential election.