America’s changing religious landscape has given rise to new accusations against classical liberalism for undermining the religious, moral, and civic resources the American experiment in self-government relies upon. Returning to more orthodox forms of faith is understandably thought the best way to revitalize those resources. Yet according to John Locke and four of America’s founders – John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Benjamin Franklin – that prescription would not encourage civic virtue but endanger the rights of religious liberty and free inquiry. Orthodoxy, the idea that belief in a particular set of doctrines and dogmas is incontrovertibly necessary to be saved, may tend to undermine civic virtue by breeding sectarianism. As John Adams complained to John Taylor in 1815: “Trace Christianity from its first Promulgation, Knowledge has been almost exclusively confined to the Clergy. And even since the Reformation, when or where has existed a Protestant or dissenting Sect, who would tolerate, A free Inquiry?” Despite the sectarian’s willingness to look past the worst “yahooish brutality,” if one dares to “touch a solemn Truth in collision with a dogma of a Sect… you will Soon find you have disturbed a Nest, and the hornets will swarm about your legs and hands and fly into your face and Eyes.” While Adams and our other founders understood that religion played a significant role in cultivating civic virtue, only a rational faith which privileged morals over doctrine could serve that function while being an ally to religious liberty and free inquiry.

Writing in his journal in 1681, Locke noted that as most men are ruled by passion and superstition; any hope to introduce peace amongst Christians and lead men to embrace religious toleration must confront such superstition. Part of the difficulty, according to Locke, was that the superstitious believe that God is pleased by ritualistic solemnity and doctrinal orthodoxy – not Christian charity. In The Letter Concerning Toleration, Locke argued that concern for religious doctrines that “exceed the Capacity of ordinary Understanding,” in fact led men to violate the principles of Christian charity. Rather than providing a reading of the Gospels that would show men that their mistreatment of those who differ from them theologically betrays Christ’s moral teaching, the Letter contends that what is most needed is to separate the business of church and state. While doing so would disarm those ambitious to use the state to persecute their theological adversaries, the ideas in the Letter alone are insufficient to solve the problem of superstitious zeal and provide for toleration.

The Letter begins with the assertion that the “chief Characteristical Mark of the True Church” is toleration, but then claims that it is “not a proper place to enquire into the marks of the true Church.” The Letter, therefore, points to a theological argument it does not provide. That argument is provided in The Reasonableness of Christianity; As Delivered in the Scriptures which seeks to reform not only men’s understanding of what it means to be Christian, but to impart a certain theological disposition. That disposition is captured by the rules to govern what Locke termed “Pacific Christians.” The Pacific Christian, in accepting all morally serious men as Christian, is unconcerned with doctrinal orthodoxy. Given that the greatest threat to Christian charity Locke saw was insistence upon doctrine and dogma, the Pacific Christian recognizes that what God has given to each man’s understanding is a matter between God and man alone, unique to their understanding.

At its core, Locke’s theology as articulated in the Reasonableness argues that the name of Christian belongs to all those who accept Christ as Messiah. Taking Christ as Messiah requires only a sincere endeavor to live in accord with Christ’s moral teaching, repenting of one’s failures to do so. All that can be demanded of each is to submit to whatever appears to them God had deemed necessary for them to believe. In this way, as Locke argues in the Letter and The Reasonableness, “everyone was orthodox to themselves.”

Hope for the arrival of a more reasonable Christianity led John Adams to request Thomas Jefferson’s help in easing the move of Unitarian Minister Horace Holley from Boston to his new post as President of Transylvania University. According to Adams, Holley had a “mind too inquisitive for Connecticut,” so had moved to Boston where he made his acquaintance. Adams lamented Holley’s departure as the city “ought always to have one Clergyman at least who will compel them to think and enquire.” He wondered, however, if “Superstition Bigotry, Fanaticism and Intolerance” would allow him to live in Kentucky. Jefferson thought he would receive a more welcome reception than Adams anticipated. “Rational Christianity will thrive more rapidly” in Kentucky than Boston or Virginia, Jefferson suggested, as its people were “freer from prejudices…, and bolder in grasping at truth.” Adams thought Holley “a Diamond of Superior Water” whose theology in appealing to “the hopes of mankind” would lead men to “juster Notions of the Universal eternal cause” so that “rational Christianity” could “prevail.”

It is in this light that one must read Adams’s oft quoted remark that “Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious People. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.” A few months earlier he had similarly remarked to an assembly of young men in Philadelphia that, while “science and morals are the great pillars on which this country has been raised,” no matter how long they live they will find “no principles, institutions, or systems of education more fit… than those you have received from your ancestors.” The question what was bequeathed to them, he later took up with Jefferson. Adams remarked that he was referring to the “general principles of Christianity,” together with the “principles of English and American Liberty.” The true principles of Christianity, he noted, while difficult to discern underneath the corruption given to them by “those who pretended to be his special Disciples,” are in essence “the principles of pure deism,” whose “moral doctrines” are conformable to “the Standard of reason, justice and philanthropy.”

Introducing a more rational Christianity was equally necessary to Benjamin Franklin. Writing to his father in April of 1738 to assuage his mother’s worries that he had fallen into heresy, Franklin began by admitting that he may have adopted some erroneous theological opinions but that “a Man must have a good deal of Vanity who believes, and a good deal of Boldness who affirms, that all the Doctrines he holds, are true…” The only way to judge another’s religious opinions is by their actions. If you think their beliefs erroneous but that “none tend to make them less Virtuous or more vicious,” you should acknowledge none are “dangerous.” In fact, Franklin argues, “vital Religion has always suffered, when Orthodoxy is more regarded than Virtue.” He, therefore, assures his parents of his confidence in Scripture’s promise that, on the “last Day, we shall not be examin’d [by] what we thought, but what we did…”

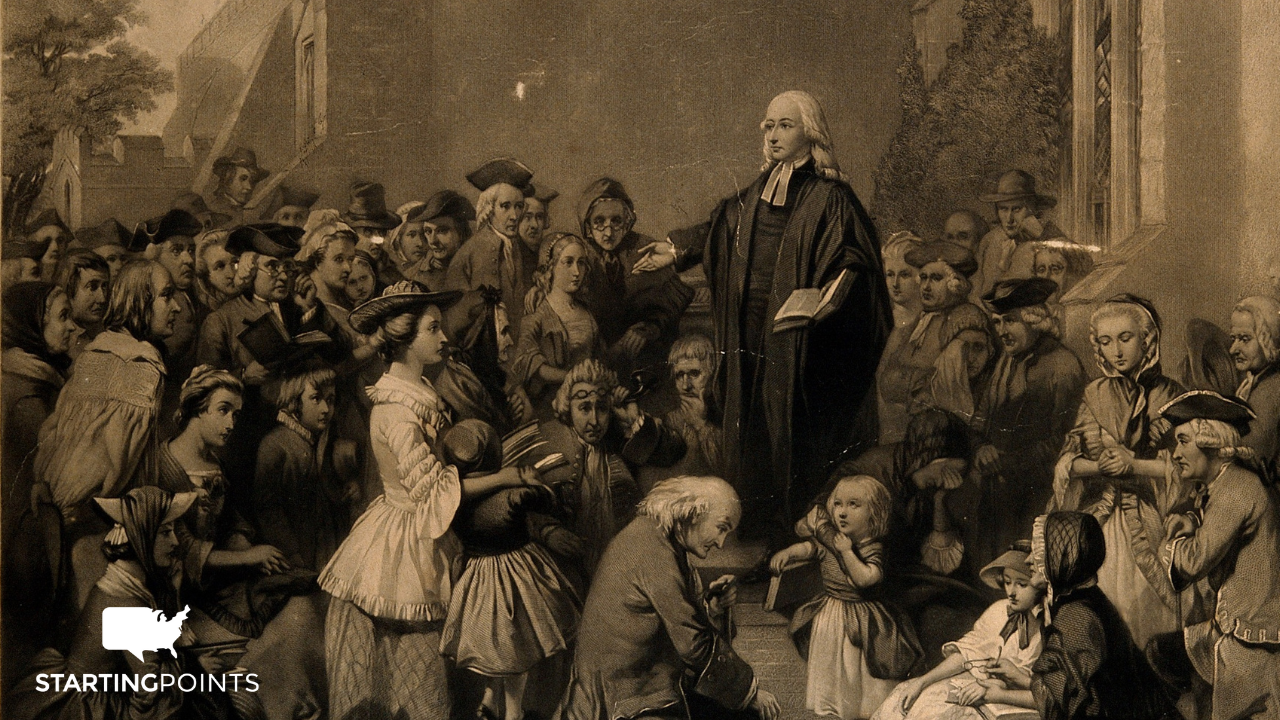

Returning virtue to its proper place within the faith, according to Franklin, requires returning to its primitive origins. Franklin’s efforts on behalf of such reform can be found in his defense of Reverend Samuel Hemphill who ran afoul of the Philadelphia Presbyterian Synod for privileging morals over doctrine. Franklin’s four pieces written in Hemphill’s defense challenged the very notion of orthodoxy by reducing Christianity, as did Locke, to a single article; accepting Christ as Messiah. For Franklin, the name Christian belonged to all who sincerely attempt to live in conformity with Christ’s moral teaching. Those who insist on orthodoxy rather than sincerity subvert the virtue of charity whose primary object is accepting one’s own fallibility and the ineluctable diversity of religious opinion.

Separating dogma from Christ’s moral teaching was of similar concern to Thomas Jefferson. For Jefferson, the cause of religious liberty and free inquiry required a return to the original, primitive religion of the man he regarded as the “benevolent and sublime reformer” of the Jewish faith. At the center of this reformation was the question of the nature of human understanding and the issue of the material basis of thought. Inquiry into that question would contribute to the reform of religion by separating the “diamonds” of rational Christianity, from the “dunghill” of revealed religion thus rendering Christianity an ally rather than an adversary of religious liberty.

In 1824 Jefferson received a package of books from the Marquis de Lafayette which included the research of Pierre Flourens. Jefferson thanked the Marquis remarking that he had “never been more gratified by the reading of a book.” The subject of Flourens’ experiments was the material basis of thought; a subject of Jefferson’s concern dating back to his university studies. Flourens documented how removing the cerebrum from pigeons, leaving the cerebellum intact, deprives the bird of its cognitive functions while preserving its powers of motion when stimulated. By confirming that thinking was materially based, Jefferson believed Flourens had provided a significant weapon for the demystification of the immaterialist notions that had “perverted” the faith into an “engine for enslaving mankind.” Jefferson, therefore, expressed his hope to John Adams that Flourens’ experiments would silence the spiritualists and usher in “the dawn of reason and freedom of thought in these United States.”

That freedom of thought would be best secured by theological and epistemic humility can be seen in a short but revealing letter James Madison wrote in reply to the Reverend Frederick Beasley in November of 1825. Beasley sought Madison’s approval of his tract “A Vindication of the Arguments, A Priori, in Proof of the Being and Attributes of God,” written to combat materialism, deism, and arguments for the eternity of the universe. Madison explained in reply that the limits of human understanding are especially discovered when men attempt to contemplate such ideas as involve the infinite. Confounded by such notions, Madison explains, “the mind prefers at once the idea of a self-existing cause to that of an infinite series of causes & effects.” Faced with this difficulty, the mind finds repose in “the self-existence of an invisible cause possessing infinite power, wisdom & goodness,” as opposed to “the self-existence of the universe, visibly destitute of those attributes.” Despite what the mind may prefer, Madison draws the conclusion that, “In this comparative facility of conception & belief, all philosophical Reasoning on the subject must perhaps terminate.” The “finiteness of human understanding” demands that the conclusions which the mind “prefers” are understood by the faithful as emerging from a desire to believe rather than a proper conclusion derived from reason.

Madison would later suggest the same to Jasper Adams in 1833, in reply to his “Convention Sermon” which claimed that Christianity is the foundation of America’s political institutions and that absent legal support its influence in the community will be lost. Madison regarded Adams’s fears as unfounded, as within the nature of man something ensures “belief in an invisible cause of his present existence and an anticipation of his future existence.” Such hopes and fears Madison claimed account for our “propensities and susceptibilities in the case of religion.” That people will continue to believe is writ large in their nature; what they would believe, however, and how they understand those beliefs, is not so determined. The dogmatic distinctions that divide the faithful, which Madison describes at times as “erroneous,” “ridiculous,” “frivolous and fanciful,” need not persist. Until men like Beasley and Adams reconcile themselves to the limits of human understanding, there will be little end, as he remarked to Jefferson upon passage of the Virginia Bill for Religious Liberty, to “the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.”

As the non-dogmatic Christianity four of our Founders sought to advance has come under increased scrutiny as too thin to sustain the republic they worked to bring into being, it is necessary to hear their arguments once again. They warn us that a return to more orthodox forms of faith is not only unlikely to revitalize civic virtue but would present a threat to religious liberty and free inquiry. Given the rising tide of illiberalism and incivility that has accompanied such calls, it is well worth re-examining the arguments of Locke and our Founders that helped construct America.