April 19 marked the anniversary of the American Revolution – specifically, the Battle of Lexington and Concord. The American Declaration of Independence justifies the rebellion by listing “a long train of abuses and usurpations [revealing] a design to reduce [the colonists] under absolute Despotism.” It explains the nature of these various abuses and usurpations as attempts by Parliament “to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us.” This was always the heart of the American complaint against Britain during the Revolutionary era. The Declaration of Independence casts the Revolution as an effort by local governments to resist and reverse a decade of centralization, thus restoring and enshrining the principle of government by consent.

In the War of Independence, American civilians took on the world’s greatest military, naval, commercial, and economic superpower. It is difficult for modern people – even those living in democracies, and even those living in the United States of America – to understand what made government by consent so viscerally important to American settlers that they risked so much for it in the face of such long odds. What made them fear and oppose arbitrary power so vehemently, when by comparison, most modern Americans acquiesce quite calmly to the application of arbitrary power on them?

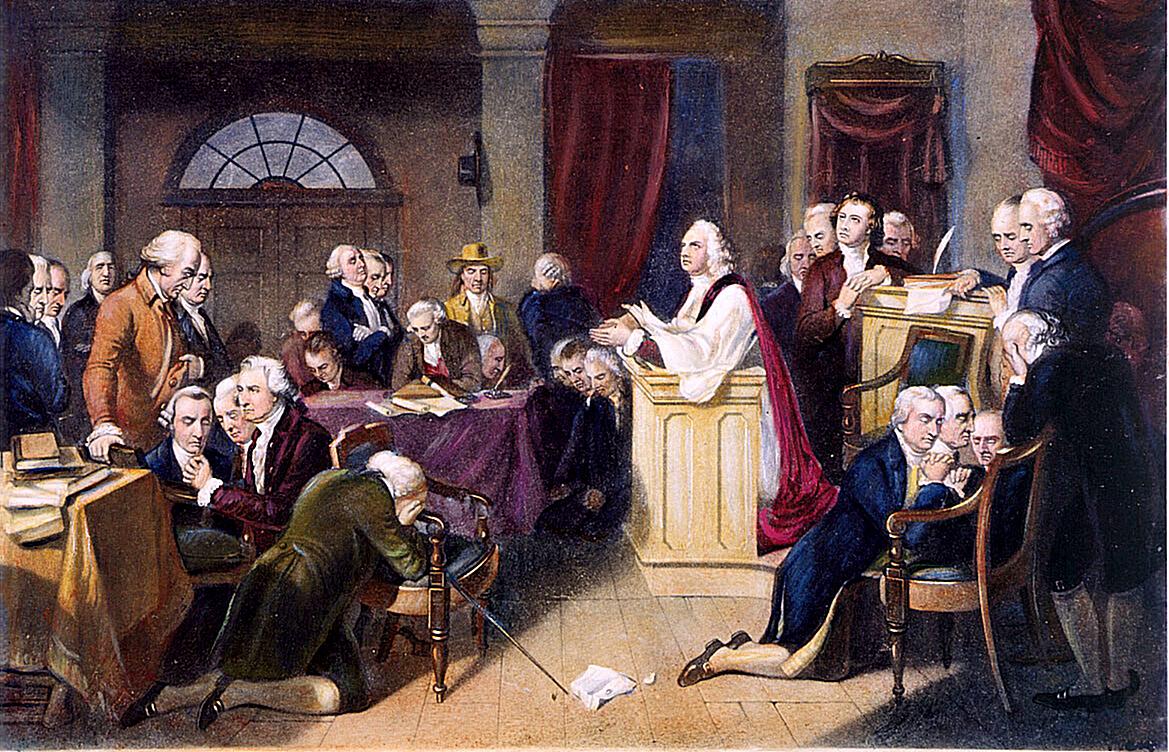

Most history textbooks trace American Revolutionary ideology to Enlightenment political philosophers and to republican principles drawn from classical history. This would strike Revolutionary Americans as odd, since hardly any of them could name an Enlightenment thinker or explain the basics of Roman republicanism, let alone explain how these relate to their support for the Patriot cause. Most Revolutionary Americans would point instead to the Bible as the source of their constitutional and political beliefs. Yet one is hard-pressed to find a textbook that identifies the Bible as a meaningful ideological influence on the American Revolution. This means that the most dominant force shaping Revolutionary Americans’ political convictions has become invisible to Revolutionary historians and students.

The British Empire had historically been a decentralized empire, with strong local governments operating autonomously under a weak central government. Within this governing structure – what today is identified as a states’ rights system – each colony governed itself according to local custom, local interests, and local circumstances. The British government had a light footprint even in royal colonies and thus governed lightly, wielding soft power within these colonies. In the decade between the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, however, Parliament worked to transform the Empire from a decentralized empire, in which local populations governed themselves, into a centralized empire governed from the center. These imperial reforms triggered suspicion, fear, and resistance among the colonists, who tried to protect the traditional system of imperial governance against these innovations.

American settlers’ attachment to government by consent is best understood as commonly British, rather than uniquely American. The intense fear of centralized governance that sparked American resistance in the 1760s and 70s had already produced two major rebellions in England in the 1640s and 1680s, and two more in Scotland in the 1710s and 1740s. What was common to all these British rebellions – in England, Scotland, and America – was a conviction that centralized power invites abuse of power because it is arbitrary by its very nature.

This British political mentality rested on the widespread assumption that people with power will abuse it. This very human problem is why Britons were so insistent on representative government – government by consent – in their towns, churches, courts of law, and in their legislatures. Everything that is associated with Anglo-American political culture flowed from this dark understanding of human nature – the fear of concentrating power in one person or in one institution is what necessitated representative juries and legislatures, and shaped the procedural protocols in courts of law and in legislatures. Likewise, the provisions articulated in the English Bill of Rights, American state constitutions, Articles of Confederation, Federal Constitution, and American Bill of Rights were all institutional solutions to the basic expectation that people with power will abuse it.

As to why the English held this dark view of human nature, opinions differ, but there is evidence that it was uniquely English. Doubtless, English history – from Henry VIII and Mary I to Charles I and Oliver Cromwell – taught Anglo-Americans important lessons about abuse of power in high places. It is also true that the English absorbed certain beliefs regarding human nature and human government from histories of ancient Greece and Rome, and from Enlightenment political theorists whose ideas trickled down to common folk through various means. But Protestantism and the Bible, not the Enlightenment and classical history, were the primary shapers of Americans’ political sensibilities.

The Bible was by far the most widely owned and read book in both Britain and America, and the Great Awakening made this Bible-centered civilization all the more Bible-centered. The Bible provided Anglo-Americans with bedtime stories, reading lessons, entertainment, moral and religious instruction, and general education about the world, including an education about human nature, human psychology, law, and political science.

Protestantism emphasized innate and immutable human sinfulness, and Biblical history confirmed and reconfirmed this theological message. The Old Testament in particular offered a vivid and insightful chronicle of human wickedness and abuse of power. When Anglo-Americans considered King Saul, for example, they knew that he was a bad king not because he was a bad man. In fact, they knew him to be a uniquely good, humble, and admirable man. It was kingly power that transformed him into a bad king.

A long line of Israelite kings followed, who likewise were wicked. Each of them confirmed the prophet Samuel’s blistering exhortation to the Israelites against instituting a monarchy. As Samuel had warned, these kings used the Israelites’ sons and daughters as soldiers and servants, they increased the tax burden to finance their palaces, ruled harshly, took property arbitrarily, and instigated wars.

This prophecy proved correct not because Samuel knew the future – he did not – but because he had an Old Testament understanding of human nature. He had a dim view of centralized government because he believed that people with power will abuse it.

As a civilization that had internalized this philosophical and theological belief about human nature, Anglo-Americans were suspicious and fearful of government officials – local, provincial, and imperial. They believed that political power naturally and predictably produced abuse of power. It is in this philosophical context that Thomas Jefferson made his stoic observation that “the natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground.” James Monroe similarly noted humans’ difficulty, “in all ages and countries, to preserve their dearest rights and best privileges, impelled as it were by an irresistible fate of despotism.”

It is this bleak view of human history that explains Americans’ vigilance and fearfulness regarding the centralizing imperial reforms of the 1760s and 70s. Ever on the lookout for creeping advances of arbitrary power over the consent of the governed, they viewed with alarm Parliamentary policies that strengthened the central government and weakened local communities’ control over their governments and courts of law.

Once independent, Americans approached the United States government with the same suspicion and vigilance. Educated by Biblical history, many of the Revolutionary generation feared that American citizens would follow the same natural impulses that transformed all historical republics into monarchies or dictatorships. With their own experience in self-government as their constitutional guide, they therefore crafted a constitution – the Articles of Confederation – that created an emasculated central government unable to impose its will on local communities. When confronted (in the 1780s) by Federalist efforts to replace the Articles of Confederation with a new constitution that promised to strengthen the central government and curtail local communities’ ability to govern themselves, American suspicion and resistance compelled the Federalists to moderate and introduce various protections for self-government in the states.

Historians who discount religion and the Bible as the primary intellectual force behind the American Revolution do so because the most prominent leaders of the Revolution were not particularly religious or devout. Moreover, these Revolutionary leaders – John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, Robert Morris, James Madison, and James Monroe – were indeed steeped in Enlightenment philosophy and classical history. This encourages historians to highlight the Enlightenment and ancient Rome as the primary shapers of Revolutionary ideology.

But the key to understanding a successful social movement like the American Revolution is not identifying why its leaders supported the movement, but what drove hundreds of thousands of Americans to support it; what led multitudes of ordinary people to risk their lives and their families’ lives and possessions for it. When one shifts attention from the rich and famous who led the Revolution to the hundreds of thousands of nameless Americans who made this resistance movement successful, the assessment of the Revolution’s intellectual and ideological roots shifts quite easily. No one can believe that American farmers, sailors, shopkeepers, dockworkers, and teenagers were reading, contemplating, and discussing Rousseau, Locke, and Montesquieu, or histories of ancient Greece and Rome. It does not make intuitive sense, and there is no evidence for it. They read, contemplated, and discussed the Bible.

The Old Testament (the Hebrew Bible) held a particularly elevated position in the religious lives and imaginations of Anglo-Americans in the early-modern era. This was partly because it was central to Protestant theological scholarship and the Protestant project of accurately translating the Bible into vernacular languages. But the Hebrew Bible resonated with English readers in particular because they identified in this chronicle of Jewish national history many cultural, spiritual, and political parallels with their own national life. This was doubly true for Anglo-Americans.

There is widespread evidence that American settlers were well versed in the Bible even before the Great Awakening. Almanacs, for example, assumed a high degree of Biblical literacy among their numerous readers. Likewise, Thomas Paine’s Revolutionary pamphlets were filled with Biblical themes and allusions; he counted on his readers to get the Biblical references he was making. These observations are not anecdotal; there is empirical evidence that the Bible – the Hebrew Bible in particular – was the single most cited work in American political literature of the founding era; much more so than the works of political philosophers like John Locke, James Harrington, or Montesquieu. This was true of political literature in England as well, and even in high literature on political philosophy – the ancient source John Locke cites most frequently in his Second Treatise of Government (1690) is the Hebrew Bible.

American resistance to British policies in the Revolutionary Era was not based on philosophical abstractions on government and law. It was the daily life experiences of countless men and women on their farms, on the docks, and in their workshops, stores, and homes that drove Americans into resistance and rebellion. What fueled this resistance movement was fear and righteous anger at imperial officials for violating English law, and for undoing traditional Anglo-American protections against such government lawlessness. The colonists distrusted and feared government officials – imperial, provincial, and local – because at Church and in their study of the Bible, they had absorbed a dark understanding of the human heart. Their distrust and fear of human governments – that is, of government officials – reflected the Hebrew Bible’s distrust and fear of human nature.

Historians’ Biblical blind spot obscures the roots of Revolutionary Americans’ political convictions. In doing so, it also encourages students to look at the Revolution not as a mass movement of common people, but as an elite enterprise. As they trace the source of Revolutionary ideas to the Enlightenment and ancient Rome, historians draw students’ attention away from the ordinary Americans who carried out the Revolution in their local communities and on campaign, and redirect it toward a small circle of hyper-educated Revolutionary leaders like Jefferson, Adams, Hamilton, and Madison.

Guy Chet is Professor of American History at the University of North Texas, and author of The Colonists’ American Revolution: Preserving English Liberty, 1607-1783 (Wiley, 2019). Portions of this essay are drawn from the book, with Wiley’s kind permission.