The election of 1856 was the most violent peacetime election in American history. For the first time, a national political party with a legitimate chance to win the presidency campaigned on an anti-slavery platform, putting a fright into Southern politicians, the slave owners they represented, and their Northern sympathizers.

After decades of blustering about secession against an eager-to-compromise Whig Party, pro-slavery Democrats were confronted with a partisan opponent that would not roll over in the face of disunionist threats.

They did not handle it well. The result was a year of politically inspired violence that stretched from the Kansas prairie to a landmark Washington hotel, from Southern plantations to the halls of Congress.

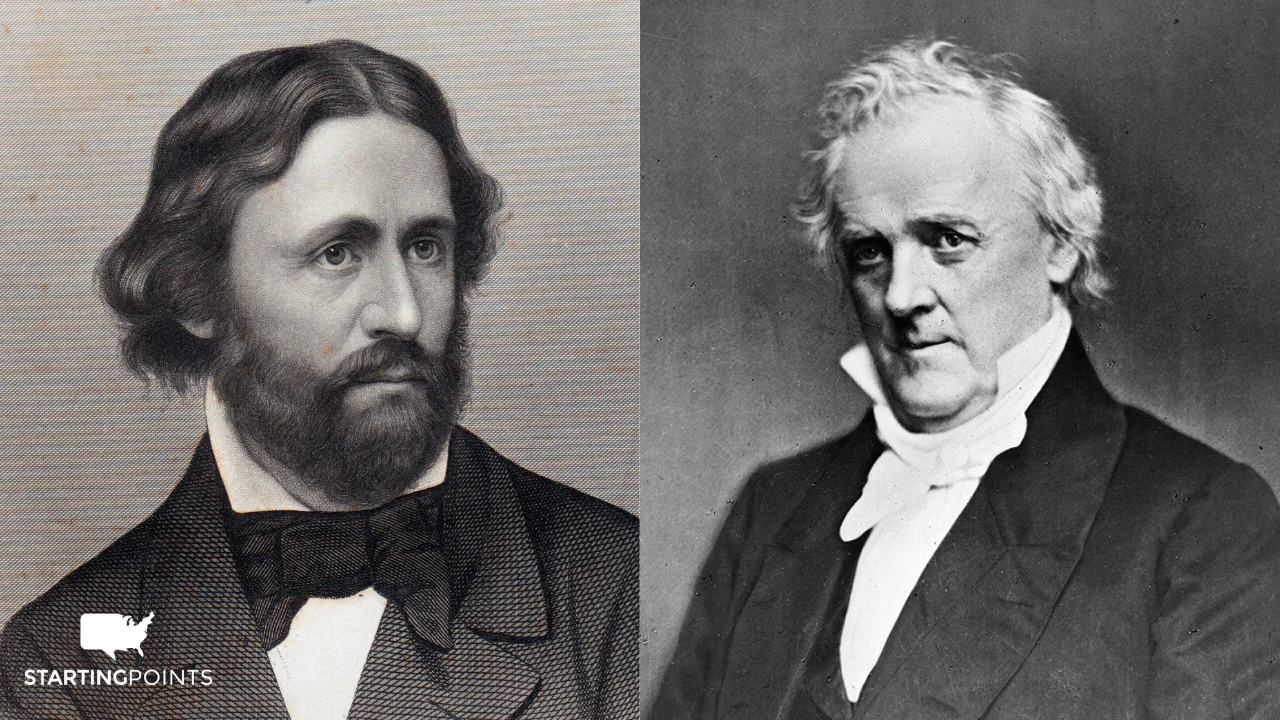

In the end, enough Northern voters decided that they feared secession more than they hated slavery. Doughface Democrat James Buchanan, a Northern man with Southern sympathies, defeated famed Western explorer John C. Fremont, the first Republican presidential nominee.

Four years later those same voters went the other way. Those intervening years saw the Dred Scott decision, Buchanan’s acceptance of an illegitimate pro-slavery government in Kansas, and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry contribute to the growing feeling that the irrepressible conflict could no longer be repressed.

The Republicans also had four more years to become a fully organized national party. And they would find a better candidate in Abraham Lincoln.

A New Party

The Republican Party was born in 1854 in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which organized those territories on the principle of popular sovereignty – allowing the residents of the territories to decide for themselves whether to allow or outlaw slavery.

The law repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 that admitted Missouri as a slave state but barred slavery in territory north of the 36 degrees/30 minutes latitude that marked the northern boundary of the new state.

Anti-slavery Whigs, Democrats, and Free Soilers opposed to the law coalesced into a new political party, the Republicans, that had virtually no support in the slaveholding South. But population growth in the North meant it could theoretically win a national election solely with Northern electoral votes.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act also drew Abraham Lincoln back into politics. Lincoln had been a state representative and one-term congressman in the 1830s and 1840s. He left active politics after the election of 1848 to practice law full time.

But he vociferously objected to allowing slavery into the territories gained by the Mexican War (which he had opposed), and rightly saw the Kansas-Nebraska Act as opening the way to an expansion of slavery. That cause drew Lincoln back onto the political battlefield.

Bleeding Kansas and Bloody Sumner

The potential for the expansion of slavery and the unsettling of the political equilibrium with the demise of the Whigs and the rise of the Republicans created instability. Violence soon followed.

In early May, pro-slavery and anti-immigrant California congressman Philemon T. Herbert shot and killed an Irish-born waiter at the Willard Hotel, a popular gathering place for Washington politicians. A D.C. jury acquitted Herbert and he returned to his seat in Congress.

Later in the month, abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts was beaten nearly to death on the Senate floor by South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks, who attacked Sumner with a cane. Sumner had delivered a virulently anti-slavery speech a few days earlier in which he attacked – verbally – a relative of Brooks, South Carolina Senator Andrew Butler.

Brooks was convicted of assault and fined $300. An attempt to expel him from Congress failed, but he resigned and then sought re-election, which he won with ease.

Two days after the attack on Sumner, John Brown led a murderous assault on pro-slavery Kansas settlers on Pottawatomie Creek. Five men were shot and hacked to death with broadswords.

Kansas had effectively been in a state of war for months, with private citizens and government-sanctioned militias launching attacks. Brown’s attack escalated the violence and most Republican politicians repudiated his tactics. But the violence in the territory gave Republicans an effective rallying cry – Bleeding Kansas – to go with Bloody Sumner.

The Pathfinder

In 1856, Lincoln was a regional player, not a national one. He had lost a contest for the U.S. Senate in 1855 to anti-slavery Democrat Lyman Trumbull, but soon became a leader in the state Republican Party.

At the national level, Republicans sought a bigger name. New York Senator William H. Seward and Ohio Governor Salmon Chase were the most prominent elected Republican officials. Nathaniel Banks of Massachusetts had been elected Speaker of the House in a contentious election in 1855.

But the party turned to Fremont. He had gained extraordinary acclaim for his four expeditions and the best-selling official report of his journey of 1843-44 in which he crossed the Sierra Nevada (against orders) in February 1844.

He played a dubious role in California’s revolt against Mexican rule and was court-martialed for insubordination. But he won global fame as the Pathfinder, although he mostly traveled routes already tread by earlier explorers and mountain men. By 1856, he was one of the most famous men in the world.

His political experience was virtually nil. He had been elected one of California’s first two senators in 1850 but served only a few months and failed to win re-election. He had a nominal anti-slavery record but had never been a leader in the cause. He was reserved, not a back-slapper, and generally refused to play the go-along-to-get-along political game. Activists loved him. The politicians were wary.

But he had an asset no other candidate could match. His wife, Jessie Benton Fremont, was the daughter of longtime Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton. She had a charisma that was the equal of her husband’s, and considerably more political savvy. She played an unprecedented role in his campaign, essentially serving as her husband’s campaign manager.

The Republican convention that nominated Fremont for president considered Lincoln for vice president. He won the second-highest number of votes, but William Dayton of New Jersey won the VP spot over the little-known Illinois lawyer.

The Democrats dumped their incumbent president, Franklin Pierce, opting instead for James Buchanan, a 65-year-old bachelor who had been in politics so long that he had once been a Federalist. Republicans played up the contrast between the virile and attractive Fremonts and the dour, never-married Buchanan.

Another party, the anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic American Party, known as Know Nothings, chose former President Millard Fillmore as its candidate. Fillmore gave Northern voters worried about disunion a place to land that didn’t involve supporting the Republicans whose victory they feared would lead to secession.

Catholic immigrants from Ireland and Germany overwhelmingly supported Democrats. Republicans tried without success to join forces with the Know Nothings. That failure would cost them dearly in states like Pennsylvania and Indiana.

19th Century Cancel Culture

Threats of secession were real, and they grew as the campaign wore on.

When Republicans swept the Maine state elections on September 8, pro-slavery men came face to face with the reality that an anti-slavery party might actually win the presidency. “The mere thought that such a thing might occur is enough to startle one,” Buchanan supporter Jeremiah Black wrote.

Buchanan himself noted that decades of Southern threats might now come back to haunt the pro-slavery side. “We have so often cried ‘wolf,’ that now when the wolf is at the door, it is difficult to make the people believe it.”

Democratic Vice Presidential candidate John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky called openly for resistance if Fremont was elected. “If the Eastern States were to unite in solid phalanx against the West, or the Southern against the Northern, they happening to have a majority, would you submit to it?” he asked a campaign crowd in Indiana after the Maine elections. “I am sure you would not, for I know you to be men. And should they further, accompany every act of their triumph with every expression of contumely and contempt, would you not believe revolution a solemn duty?”

Virginia Governor Henry Wise promised individual retribution, declaring “any one who permits his name to go on a Fremont electoral ticket guilty of contemplated treason to the State.” Wise ordered the Virginia militia to mobilize and urged other Southern governors to do the same.

John C. Underwood, a Virginia lawyer who had served as a Fremont delegate at the Republican convention, was forced by threats to flee the state. A chemistry professor at the University of North Carolina was fired for supporting Fremont.

This 19th century cancel culture had an even uglier side.

In the South, slaves held clandestine meetings to discuss what they saw as the promise held out by the Fremont campaign. One group in Texas even conspired to obtain arms and flee to Mexico. Ironically, it was Democrats who inspired such hopes by exaggerating the Republicans’ simple dedication to stopping the spread of slavery into a full blown abolitionism that they did not espouse.

Slaveowners inevitably got wind of these meetings. The result was a string of violent attacks by vigilante mobs. More than 30 enslaved people were murdered across the South over the course of the campaign.

The Path to Victory

Voters saw the election as important. Turnout was 78.3 percent – 83 percent in the North – the highest since 1840. Buchanan won only 45.3 percent of the vote. But he swept the South and held enough of the North to defeat Fremont and Fillmore (who won only one state, Maryland).

But the warning signs for Democrats were clear to all. The Republican theory, that they could win the presidency with only Northern votes, now looked more than plausible. Buchanan won five free states – New Jersey, Illinois, and California by plurality, Indiana and Pennsylvania by tiny majorities.

This, in a year in which the Republican Party was barely organized nationally and hardly at all in some states, with a popular but inexperienced candidate who did not get on well with the politicians leading his party. If, in 1860, they could nominate a better candidate with broader appeal in the closely contested states, the path to victory was clear.

Lincoln’s victory in 1860 owed much to his own talents. But the difference between 1856 and 1860 was largely attributable not to personalities or organization, but to the events of 1857 to 1859 that persuaded enough Northern voters to hate slavery more than they feared disunion.

John Bicknell is the author of Lincoln’s Pathfinder: John C. Fremont and the Violent Election of 1856 and America 1844: Religious Fervor, Westward Expansion and the Presidential Election That Transformed the Nation. His next book, due out in 2025, examines the relationship between Lincoln and Fremont during the Civil War.