During and after the 2016 presidential campaign, many commentators wondered how U.S. politics had devolved into the political circus witnessed that election season. Especially puzzling was the support that evangelical Christians, adherents to a faith that emphasizes morality in all facets of life, gave to the Republican candidate—the twice-divorced, coarse-talking, oft-bankrupt Donald Trump.

Looking at the intersection of presidential campaigning and morality in recent decades is helpful for understanding where the United States is headed as the 2020 election approaches. Examining the early decades of national politics, however, shows that the United States has a long history of dysfunctional campaigning centered on moral arguments.

Political morality was common enough in the earliest presidential elections. In the 1796 contest between Federalist John Adams and Republican Thomas Jefferson, a political cartoon entitled The Providential Detection depicted Satan and “Providence” watching Jefferson attempt to destroy the Constitution on a burning “Altar to Gallic Despotism.” Four years later, Federalists argued that a Jefferson victory over the incumbent Adams would lead to the disintegration of American morality: “Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will all be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of distress, the soil will be soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes.”

In 1804, President Jefferson found himself the subject of another political cartoon. The Philosophic Cock focused on his alleged relationship with an enslaved woman, Sally Hemings. Federalist engraver James Akin drew Jefferson as the rooster and Hemings as the hen, with the caption, “Tis not a set of features of complexion or tincture of a Skin that I admire.” Astute Americans would have noted the multiple meanings of “cock,” including the synonymous rooster; the sexually vulgar euphemism; and the nod to the French headwear, the cockade, a symbol of the recent revolutionary upheaval.

Some of the rhetoric of early presidential elections was intended to enflame moral outrage, but the ubiquity of this rhetoric was tempered by the lack of true campaign organization and activity. Between 1828 and 1840, however, mudslinging campaigns, with moral questions serving as a major theme, became a permanent part of U.S. political culture.

BETWEEN 1828 AND 1840, MUDSLINGING CAMPAIGNS, WITH MORAL QUESTIONS SERVING AS A MAJOR THEME, BECAME A PERMANENT PART OF U.S. POLITICAL CULTURE.

The 1828 campaign between incumbent John Quincy Adams and challenger Andrew Jackson was especially nasty. Adams supporters pointed to Jackson’s many instances of immorality. They noted his execution of U.S. soldiers during the War of 1812 and two British nationals during the First Seminole War. They also emphasized his violent altercations and duels. Additionally, Jackson’s marriage became a topic of criticism.

Rachel Jackson’s first husband divorced her on the grounds of committing adultery with Jackson. When Jackson helped his friends produce witnesses to attest to Rachel’s character, Adamsites reveled in pointing out “the despicable character of Jackson’s defence” and observed, “the moral sense of the community begins to assert its proper influence, and assign to seduction and adultery their appropriate estimation.

One final area of criticism was Jackson’s involvement in the slave trade. His “trafficking in human flesh,” according to his opponents, demonstrated Jackson’s “total disqualification and unfitness for office.” As if the truth were not enough, anti-Jacksonians fabricated tales as well. One Cincinnati newspaper editor spread the unfounded rumor that Jackson’s mother had been a prostitute and that he was the product of one of her interracial encounters.

For their part, Jacksonian Democrats accused the president and Secretary of State Henry Clay of cheating to steal the 1824 election. Clay’s corrupt actions, according to Jackson, left him “like Lucifer, . . . politically fallen, never to rise again.” Democrats also investigated Adams for using government funds to purchase gambling devices (i.e., a billiard table and chess set). While the charge of improper use of taxpayer funds failed to stand up to scrutiny, Democrats used it to good effect. “When we find the fathers and matrons of our country engaged in persuading young men from practices which lead to destruction,” one Jacksonian editor wrote, “we greatly fear that the too frequent answer will be, ‘Why the President plays billiards!”

Democrats even argued that while serving in the court of St. Petersburg, Adams had acted as a pimp for the Russian tsar. This absurd charge, as well as others, underscored the breaching of decorum that was taking place in presidential campaigning. At the heart of these several true indictments and false accusations, on both sides, was the questions of which candidate was most morally fit to lead the nation.

Partisan insults intermixed with moral arguments remained part of the narrative in the 1832 campaign.

Supporters of National Republican challenger Henry Clay once again focused on Jackson’s alleged propensity towards violence. They accused the president of giving supporters hickory clubs “cut from his own farm” and encouraging them to take to the streets and use them against his critics.

Democrats, meanwhile, reveled in sharing rumors that Clay “spent his days at the gaming table and his nights in a brothel.” His election, they declared, would allow “embezzlers, speculators, and defaulters” to take control of the government, as they had during the John Quincy Adams administration.

The campaign of a third party in 1832, the Anti-Masonic party, was based on moral opposition to Freemasonry. This secret order was associated with Enlightenment reason, the antithesis in some people’s mind of Western Christianity. While William Wirt proved a reluctant Anti-Masonic presidential candidate, and the party’s campaign was often milquetoast, even Anti-Masons roused themselves long enough to accuse Democratic vice-presidential candidate Martin Van Buren a “modern Machieval” who was “electioneering for himself and the Grand Master of masonry.” Still, compared to all the bitter moral barbs flung in 1828, the 1832 election was mild by comparison.

However tepid the 1832 contest was, morally focused political rancor returned full-throated in 1836. In between the two elections, the National Republicans transformed into the Whig party, whose members united in their opposition to Jackson and his policies. The Whigs also positioned themselves as the party of morality. They opposed slavery, supported temperance and Sabbatarianism (i.e., setting aside Sundays solely for spiritual enrichment and growth), and generally conceived of politics as a Manichean struggle, in which they were on the side of good and the Democrats were on the side of evil. Helping the Whigs’ moral framing of the nation’s politics was the fact that Democrats generally were on the opposite side of each of the above issues.

Entering the 1836 campaign, Whigs transferred their hatred of Jackson to his anointed successor, Martin Van Buren. “Van Burenism is the common sewer for all the filth of the country,” proclaimed one newspaper editor, whose list of “filth” included women’s equality, racial equality, and religious pluralism (in the form of the new Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

Whigs also presented Van Buren as an out-of-touch elitist. In their view, he was trying “to pass himself off as a true workingman’s democrat” when he was, in fact, “a proud, rich nabob, who dashes through our streets in a fine coach, with all the pomp and parade of an heir apparent, and who is attended by English waiters, dressed in livery, after the fashion of a British lord.” Implicit in this latter criticism was the distinction between the moral character of a “true workingman’s democrat” and the sin of decadence associated with the gentry.

Also bearing the brunt of moral condemnation in 1836 was Democratic vice-presidential candidate Richard M. Johnson. A War of 1812 hero, Johnson found himself subject to attacks for successive interracial relationships with two enslaved women, Julia Chinn and Cornelia Parthene. Critics declared that it made no difference that Johnson was involved with “a jet black, thick-lipped, odoriferous negro wench,” an unconvincing claim undercut by the invocation of racist stereotypes that almost certainly were intended to stoke the flames of southern enslavers’ outrage.

These racist arguments were repeated in various forms throughout the campaign. For example, the pseudonymous “Virginius” correspondent to the Richmond Whig worried that a Democratic ticket victory would produce “bevies of mulattoes” living in Washington, encourage slave revolts, and leave white women vulnerable to violations of their “purity” and “chaste dignity,” i.e., rape by enslaved men. The rhetoric of the 1836 campaign reflected the increasing use of Christianity to argue for slavery’s immorality, a critique that often assumed that enslaved African Americans were inherently sinful as well.

THE 1840 ELECTION ANSWERED ANY QUESTIONS ABOUT THE PERMANENCY OF MORAL CAMPAIGNING.

The 1840 election answered any questions about the permanency of moral campaigning. Whigs once again carried the attack to the Democrats. Whig congressman Charles Ogle took to the floor of Congress to condemn Van Buren for his extravagant expenses while living in the White House. Ogle also implied that the president was depraved for ordering landscapers to construct hills around the White House that resembled “AN AMAZON’S BOSOM,” complete with “a miniature knoll or hillock on its apex, to denote the n—ple.”

The Whigs expanded their moral criticism from Van Buren to include the entire Democratic party. They argued that Democrats looked to precipitate “the OVERTHROW OF THE CHURCH IN ALL ITS FORMS AND SECTS, and the destruction of the ministers of religion.” Whig minister Calvin Colton asked American Christians if they were “willing to give up their rights of conscience, their religious ordinances, their holy temples, to the desolating sweep of an infidel savage dynasty—and such a dynasty of lust, and fire, and blood?” Even Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison joined in, calling Democrats “false Christs” who were attempting to deceive true believers in the Christian faith.

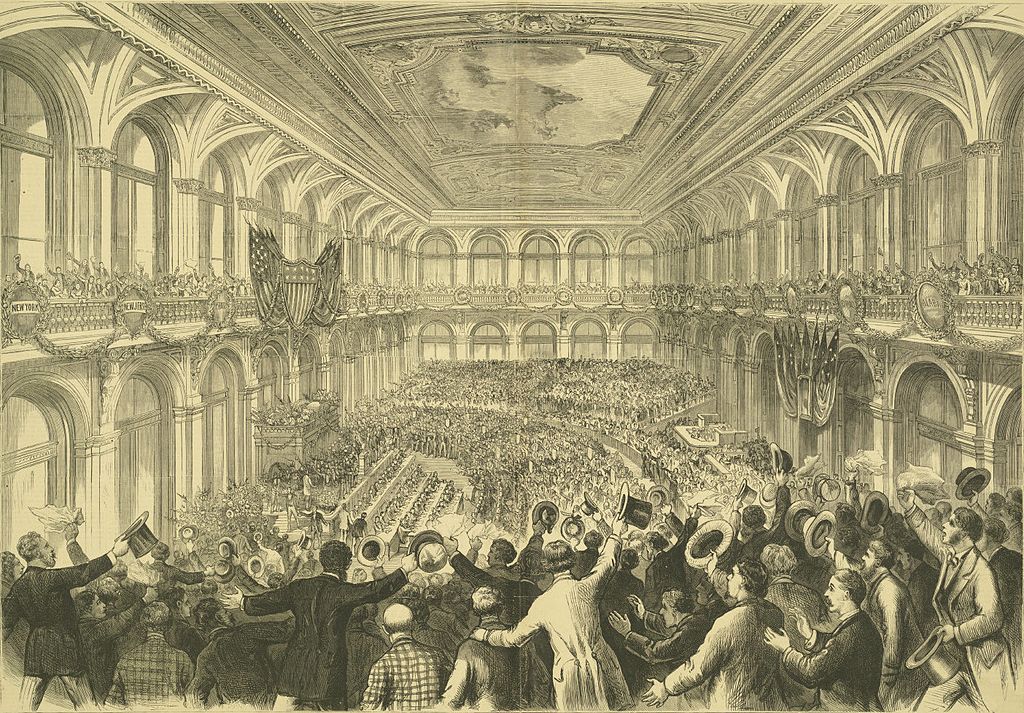

Whig campaign rhetoric clearly shows their belief that their opponents were irreligious heathens intent on destroying the nation’s moral fabric and that they themselves were Christ’s representatives charged with saving Americans from Democrats. Describing the contest in his state, Tennessee Whig James Campbell wrote, “In each county we will have a sufficient number of local preachers, to make war upon the Heathen, & carry the glad tidings of our political salvation to every corner of their counties.” Another Whig invoked apocalyptic imagery by calling the 1840 election “the battle of Armageddon.” “It will be the greatest battle ever fought,” he concluded.

Democrats were less comfortable injecting religious morality into the 1840 campaign, but they were not immune to the rhetoric. The Whigs’ “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” campaign motif presented Harrison and his supporters as salt-of-the-earth commoners who embodied traditional American values. In particular, hard cider, meant to evoke images of hard-working Whig farmers, allowed Democrats the opportunity to construct their own moral criticisms by focusing on the evils of alcohol. Groups of Harrison supporters who met in Tippecanoe Clubs were derided as “hard cider fops” who spent their meeting “gambling, betting, bragging, boasting and cheating.”

One anti-Whig political cartoon, entitled Going Up Salt River, depicted a Harrison-faced donkey carrying Clay, Massachusetts Whig Daniel Webster, and Virginia Whig Henry A. Wise. As the donkey steps into “Salt River” (according to scholar Liz Hutter, “Salt River” was a symbol of political defeat), Webster expresses concern that they will run out of hard cider. Wise assures Webster, “Don’t be frightened we have plenty lashed to the stern!” [Public domain image available at LoC: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2008661384/] These criticisms failed to stick, however. The Whigs prevailed in 1840, although it proved to be a short-lived victory when Harrison died one month after taking office.

EARLY PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGNS TRAFFICKED IN SLANDER, SEXUAL INNUENDO, AND VICIOUS PERSONAL ATTACKS IN THE SERVICE OF UPHOLDING MORALITY.

It may not be comforting to realize that early presidential campaigns trafficked in slander, sexual innuendo, and vicious personal attacks in the service of upholding morality. We may even want today’s candidates to change the tenor of their campaigns or, at the very least, to be as consistent in their expectations about morality for themselves as they are for their opponents. But until voters hold them accountable, there is no reason to think that aspirants to the White House will find any reason to take steps to conduct more honest, less hypocritical campaigns.

Mark R. Cheathem is professor of history at Cumberland University, where he also directs and edits the Papers of Martin Van Buren. His most recent books are The Coming of Democracy: Presidential Campaigning in the Age of Jackson (Johns Hopkins University Press) and Andrew Jackson and the Rise of the Democratic Party (University of Tennessee Press).