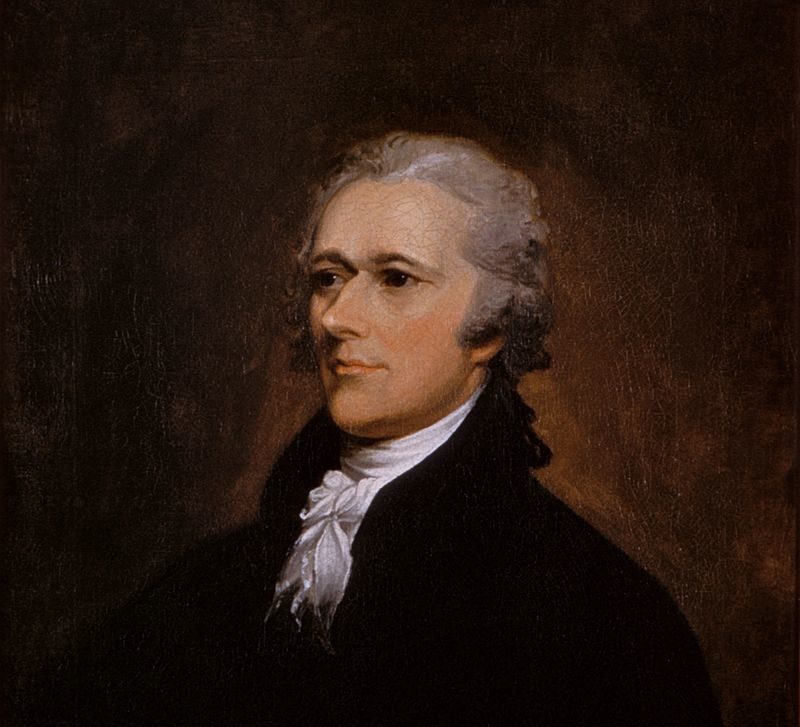

He smote the rock of the national resources, and abundant streams of revenue gushed forth. He touched the dead corpse of the Public Credit, and it sprang upon its feet.

So reads the inscription on the pedestal of the statue of Alexander Hamilton, in front of the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. The quote—originally from a toast by Senator Daniel Webster in 1831—fairly well encapsulates how most Americans at most times seem to have viewed Secretary Hamilton. He was a financial wizard, a genius with money matters, and administrator of the young nation’s debt troubles and pecuniary odysseys.

Given the apparent mundanity of financial history in general—especially compared to other contemporary American questions like slavery, westward expansion, U.S. foreign policy doctrine, and the precise interpretation of the Constitution and federalism—it is tempting to acknowledge Hamilton’s financial genius as the progenitor of modern American capitalism, and probe no further. But a deeper look at the effects of Hamiltonian capitalism—especially its sociological effects, and then its geopolitical effects—suggests that Hamiltonian capitalism is in fact integral to understanding American political culture more broadly, and subsequent historical development. Even without understanding its mechanics, putting it in historic context clarifies a lot of trends ongoing at the time, and provides a useful backdrop for the events of the early 19th Century and beyond.

The new American states, by the 1780s, remained essentially slow-paced, stagnant, near-subsistence economies, dominated by the functional equivalents of local aristocracies. Bustling industry, and the social opportunity that came with it, was largely confined to coastal towns and cities.

Hamilton’s well-known and shallowly-understood batch of policies—the assumption of state debts by the Federal Government, the imposition of bounties to spur domestic industry, the establishment of the Bank of the United States, various other administrative projects—created a national economy and put America’s debts on the path to payment, as is well-known. But those policies also wound up breaking the monopolistic power of local oligarchs, be they the Clintons of New York or the Randolphs of Virginia, and opening up pathways to capitalistic opulence for lower-class Americans previously confined to the rural countryside.

And at the same time, this centralization of economic power ensured a modicum of stability and predictability for the United States economy as a whole, and created a national market for cross-state investment and commerce where previously very little had existed. Slowly but surely, Hamilton’s empire of credit and capital spread out from its urban citadels to the towns and countryside, altering the very fabric of American life by redirecting the means and norms of commerce and labor down more efficient, productive channels. Through all this, Hamilton “smote the rock of the national resources,” and the subsequent economic vigor and might of the young United States was the essential backdrop to its ascendant international influence, its westward expansion, its increasingly wicked sectionalism, and all the rest.

The best source on all this is the late Forrest McDonald’s 1979 magnum opus, Alexander Hamilton: A Biography. McDonald claims that Hamilton, at the start of his political career, “set out to effect what amounted to a social revolution.” Specifically, and controversially:

to make society fluid and open to merit, to make industry both rewarding and necessary, all that needed to be done was to monetize the whole—to rig the rules of the game so that money would become the universal measure of the value of things. For money is oblivious to class, status, color, and inherited social position; money is the ultimate, neutral, impersonal arbiter.

The means by which Hamilton accomplished this transformation—an intricate combination of fiscal administrative machinery and deft political maneuvering unparalleled by any American financier for at least another century—are the subject of McDonald’s entire book, and cannot begin to be covered here.

It may not be immediately obvious, though, how equality through acquisitiveness transforms social order—so let’s look at it a bit more deeply.

McDonald claims that Hamilton believed his countrymen, in the 1780s, to be backwardly provincial and unproductive, if not downright lazy. A more charitable interpretation of the American yeomanry, one towards which Thomas Jefferson would doubtless be sympathetic, sees small farming, local communitarianism, and general independence of existence as both the seeds and the bulwarks of American liberty. In rural counties dotted with homesteads and small towns, the Jeffersonian Republicans believed face-to-face and deeply personal interactions would lead to a purer, more disinterested form of democracy; individuals could pursue their own pursuits of happiness in a stable environment of republican virtue and fellow-feeling.

This Jeffersonian temperament exuded a sense that all public things are better at a small, local level; and that the virtue and education of citizens, the responsiveness and representativeness of governments, and the dispersion and division of power are far more crucial to the maintenance of American liberty than the machinations of states, markets, factions, and parties. It tended to be suspicious of institutional modernity, and exhibited a sort of standpatter approach to innovation in economics and government.

A political culture like this very American one is probably more likely to see economic disruption as the machination of cabals of political elites than as a natural process, and it may be more or less right about that. But if those cabals of political elites can harness that disruption to restructure American economics and society in fundamentally useful and benevolent ways—as happened in the 1930s and 1940s with the rise of the managerial economy and welfare state, as happened in the late 19th Century with the rise of the industrial economy, and as Hamilton paved the way in the 1790s with the transition from an entirely agricultural economy to a more monetized and commercial economy—the whole country is made better off for it.

In the particular situation of the 1780s and 1790s, much of American lethargy could be attributed, so Hamilton thought, to the fact that neither opportunities for opulence nor responsibilities for debt were taken particularly seriously by most Americans. Neither fearing debt nor desiring wealth, and thus not being particularly industrious, the majority of Americans simply lived and worked in their local environs, lorded over by plantation oligarchs in the countryside who monopolized the local economies and dominated state and local society.

In the process of having the federal government assume the states’ Revolutionary War debts, and setting up a periodic plan of payment for those debts which involved federal guarantees upholding the sanctity of contracts, and thus stimulating an increased flow of money through the economy, and finally by dramatically expanding the availability of credit to many more people in all classes of society through banking reforms, Hamilton’s program stimulated city-style economic growth and opportunity in parts of the country where it had never been the norm. Money began to matter for social status and political power; as money rose, traditional social status and membership in the petty elites began to fall, becoming relevant primarily to the degree that the economic assets of the old plantation lords were still prominent over those of the rising mercantile middle classes.

The moral effects of this economic transition should not be underestimated, especially in light of the functional communitarianism of late-18th Century American society. In a society based primarily on the household, the family farm or the village, where everyone knows and trusts each other, debts can go unpaid for long periods, and commitments can proceed at a leisurely pace. In a society based primarily on the individual, the entrepreneur, and the firm, where everyone is equally liable to the impartial judgment of contract law, debts suddenly matter more, and commitments require prompt fulfillment. A local and traditionally-ordered society might be unproductive but firmly bound by custom, a deep and casual web. An expanding and contractually-ordered society might be extremely productive, but bound primarily by contract, a cruel and efficient web.

At the individual level, it is easy to imagine someone of an average level of talent, possessing no sublime genius or profound passion, simply working enough to get by. In a society like pre-revolutionary rural America, that might mean no more than harvesting the crops, managing the affairs of your own farm, bartering every once in a while for goods, resentfully paying your taxes to a government you’ll never see, and dedicating the majority of your free time to leisure and communal culture. In a society like early republican urban America, that would probably entail the weighing and balancing of innumerable commitments, the jealous guardianship of one’s finances, the prompt paying of debts and taxes, a steady drumbeat of consumer spending, and most of all never-ending work, with some time set for leisure and enjoyment. People living in a society dependent more on cash-flow than on personal relationships are, by necessity, more productive than those living in the reverse.

It’s not only the carrot of greed that ensures this productivity; the stick of fear plays a crucial role. In a dynamic economy, payments come due, and debts need to be paid. No one wants to be impoverished; they fear not only the material discomfort, but the shame that comes with it. McDonald, summarizing Hamilton’s thinking on all this: “How things are done governs what can and will be done—the rules determine the nature and outcome of the game.” Monetize the American economy, and Americans will be forced to live industriously.

This is the social context, then, in which Hamilton’s financial plans ought to be read. Elitist though he could be, Hamilton’s financial work paved the way for Americans to find more opportunities to rise above their station, and break free from the dominion of local oligarchs. An oblique contribution to American democracy, perhaps, but a real contribution no less.

Moreover, Hamilton’s efforts to spur industriousness as a broadly-exhibited American habit contributed mightily to America’s harnessing of its industrial revolution, which lay only a few decades in the future. As steam power, telegraphy, mass production, and other technological wonders transformed various aspects of American economic life, it was Whigs with updated, democratized, expanded versions of Hamilton’s original policies, who forged the North into the powerhouse it gradually morphed into. The trends of rural-commercial social tension and conflict, nascent by the 1780s, only worsened throughout the antebellum period. And the brief apocalypse of the Civil War proved just how superior Hamilton’s industrial system was, when push came to shove, to the agrarian local oligarchies Jefferson preferred which devolved in due time into the Confederacy. By Reconstruction, the old provincialism was more or less dead, and a new era of conflicts between labor and capital was already developing.

But this merely confirms the sheer boldness, and historical prescience, of Hamilton’s money revolution in American economics. Social hierarchy and pseudo-aristocracy exist in America today only along the axis of money—never independently from it or prior to it. Hamilton’s socioeconomic vision of America essentially came to be, and was useful as well in turning the United States into a great power in the 20th Century.

There have, of course, been moral costs as well as moral benefits. But Hamilton himself once replied to such concerns:

Tis the portion of man assigned to him by the eternal allotment of Providence that every good he enjoys, shall be alloyed with ills, that every source of his bliss shall be a source of his affliction—except Virtue alone, the only unmixed good which is permitted to his temporal Condition.

Luke Nathan Phillips is the Editor of Better Angels’s opinion page, and lives in Northern Virginia.