As scholars, advocates, and citizens from Indigenous societies across the Americas have argued since the beginning of European colonization, “Indigenous sovereignty” consists in the power and right of Indigenous peoples to govern themselves and their relations with other societies on their own terms. In short, Native nations have a right to govern through their own philosophical, juridical, and institutional frameworks. Such frameworks of Indigenous sovereignty have evolved both independently of and in relation to the settler-colonial societies that have coercively and unjustly erased and incorporated Native nations’ bodies, political institutions, and stolen territories to form the colonial nation-states that occupy their lands today.

In refusing these pervasive, ongoing structures of colonial violence, Indigenous sovereignty rests not only on an appeal to the specificity of the historical and present-day experiences of Indigenous peoples within the US polity, but also advances a more ethically capacious vision of decolonization through more universally valid international principles. These principles include the equality of all peoples, the right of all peoples to self-determination, and the collective and individual (human) rights to be free of subjection to systemic state violence. By contrast, US colonial claims to power over Indigenous peoples stem from an unbroken history of colonial conquest; as such, they rest on little more than the unsustainable and indefensible idea that “might makes right.”

One prominent intellectual strategy that has been used to justify the claims of Indigenous peoples to sovereignty (often by non-Indigenous scholars like me) is to represent those claims as a profound challenge to liberal or democratic-republican norms of law, policy, and politics. According to this account, because Indigenous sovereignty prioritizes collective, sovereign rights (“nations within”) over the rights of individuals primarily in their affiliation as citizens of the United States, the rights of Indigenous peoples carve out a significant yet historically and normatively justifiable exception to the liberal-democratic monopoly on justifying the terms of political rule. Call this the “exception” argument for Indigenous sovereignty.

In my contribution to this symposium, I advance an alternative argument for Indigenous sovereignty, which instead encapsulates how support for Indigenous sovereignty prioritizes the connections between the individual and collective rights and freedoms of the citizens of Native Nations in the US. To put the point in slightly different terms, Indigenous sovereignty encompasses those practices of self-government that creatively respond and construct alternatives to the connected forms of individual and collective violence that (our) colonial society imposes on them.

Because colonial domination to this day targets Indigenous peoples both as individuals and as collectives, Indigenous sovereignty is better understood as a framework committed to norms defending and (re)making of Indigenous peoples’ individual and collective freedoms at once. Indigenous societies experience their self-determination as a way of making individual and collective protections and freedoms into mutually reinforcing structures that secure well-being in connection to one another. Call this the “connection” argument for Indigenous sovereignty.

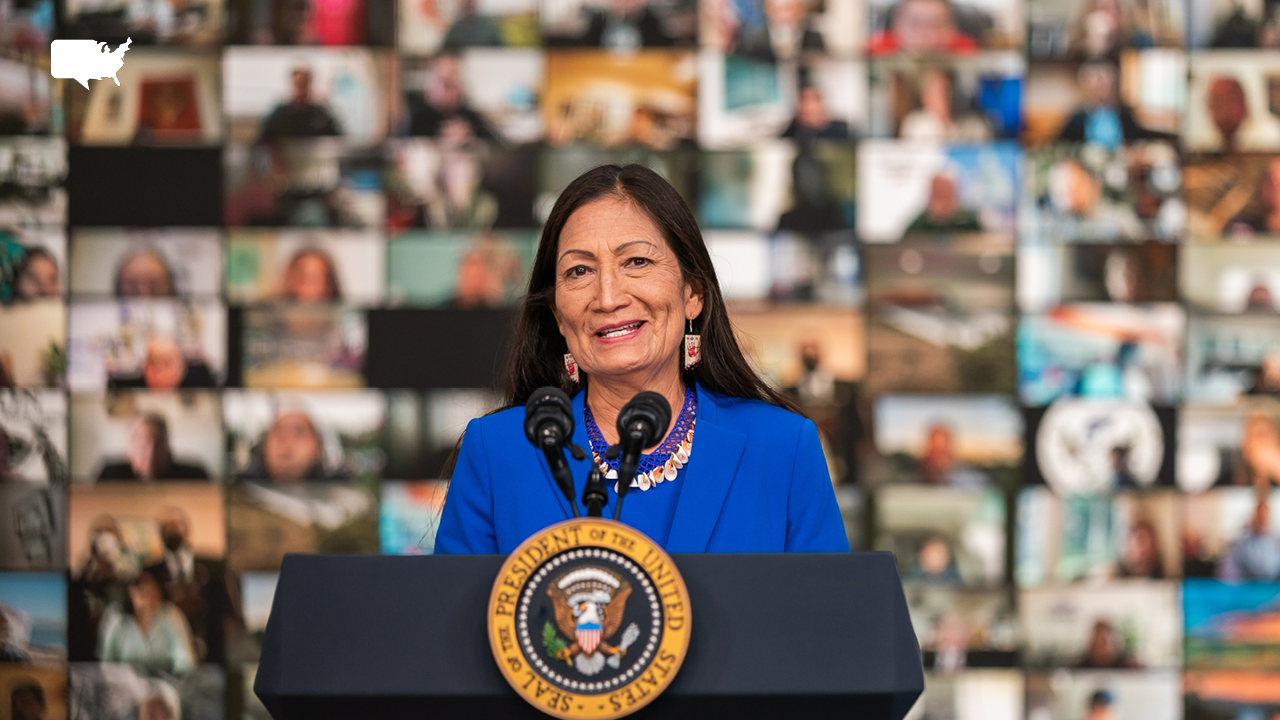

Why put forward this alternative? What is at stake, practically speaking? At stake in making the connection argument in defense of Indigenous sovereignty are very practical questions deeply contested in the US today. In fall 2022, the US Supreme Court will hear Haaland v. Brackeen, a case to determine the constitutionality of key provisions of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA).

According to federal Indian law scholars such as Maggie Blackhawk and my Michigan colleague Matthew L.M. Fletcher, the case could have profound implications for federal Indian law in its entirety. The story of ICWA is of a piece with the longer history of Indigenous peoples’ resistance to conquest and genocide at the hands of the United States and its European predecessors. Well into the 1970s, US state child welfare agencies successfully campaigned alongside non-profits and predominantly white Christian religious groups to systematically remove Indigenous children from their families and place them into white foster and adoptive homes. In some cases, child welfare agents literally stole Native children from their own front yards and their parents and/or extended family had no recourse to get them back. The numbers were staggering at the time of ICWA’s passage, with an estimated 25% to 35% of Native children separated from their families and, of those, 90% placed in non-Indian homes.

ICWA was and is one of those pieces of legislation that stemmed from Indigenous peoples’ post-World War II mobilizations. These movements scaled all the way from the development of community-based institutions of education and child welfare to defending their sovereignty and rights at the United Nations in the context of worldwide national liberation movements. On the strengths of the insurgent energy created by the global Red Power Movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s, ICWA was among a series of important legislative reforms that tribal advocates forged in the hopes of ushering in a new era of tribal self-determination. ICWA, as with other legislative landmarks, had two purposes: to defend against colonial violence to their communities that had taken (often barely more implicit) new forms and to create institutional structures that would rebuild and enhance the capacities of Native nations to govern themselves on their own terms.

ICWA is, therefore, an important expression of Indigenous sovereignty: The legislation aims to protect the connected basic rights and freedoms of Indigenous children, parents, relatives, families, and communities. It does so primarily by securing tribal jurisdiction over child welfare placements, which give preference to placements of Native children with their extended family and tribal nation. In this case as with others, the freedoms and flourishing of Indigenous individuals and the freedom of Indigenous communities are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. The connection argument brings sharply into view how Indigenous sovereignty works counter to (the colonialism of) family separation.

To be sure, ICWA is far from a panacea. Even now, with the protections of ICWA legally well established and supported as the “gold standard of child welfare laws” for its focus on kinship placement by the vast majority of states across party lines, a recent 2020 study shows that American Indian and Alaska Native children are still “overwhelmingly exposed to inequitable system contact.” In plain language, Indigenous children are, to this day, removed from their families and communities at alarming rates tantamount to genocide under article II of the UN genocide convention (wherein “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” is specifically defined as act of genocide).

It is no wonder, then, that legal scholar Dorothy Roberts has argued that the child welfare system more generally is really a highly coercive engine of family separation for groups already subordinated and racialized in US society. In this sense, Roberts contends that this system is more accurately thought of as a “family policing system” the aim of which is to police, regulate, criminalize, and cruelly degrade (non-exclusive) groups of Black, Brown, Indigenous, migrant, working class, and poor families. These practices are not the result of efforts to remove children from abusive situations. We know this because child abuse occurs in similar rates across racial and socioeconomic groups in US society. Instead, child welfare agencies disproportionately target those with fewer resources and power in society by using poverty, citizenship status, and homelessness as proxies for parental and familial (especially maternal) deficiency and the grounds for painful family separation that feed children into situations like foster care that are statistically more likely to be sites of abuse and trauma. Like its more studied and criticized counterparts in the formally carceral and policing arms of the state, then, the family policing system equally requires a full scale overhaul—that is, abolition and decolonization. From this vantage point, Indigenous sovereignty as exercised via ICWA is one imperfect bulwark of self-defense and care by and for Native nations against their subjection to the social hierarchies and systemic violence of which family policing and separation is a vector.

Now, ICWA is being challenged in the Brackeen case by right-wing aligned law firm Gibson Dunn, the attorney general of Texas, and three white families who sought to (and in two out of the three cases already successfully did) adopt Native children via the foster care system. On the other side, the Departments of Interior, Health and Human Services, and (as intervening defendants) the Cherokee Nation, the Oneida Nation, the Quinault Indian Nation, and the Morongo Band of Mission Indians will defend ICWA as an extension of the political status of Indian tribes as sovereigns with a slate of differentiated rights both against and within the US constitutional order.

On what grounds is ICWA being challenged? Among other points, the petitioners challenging ICWA cite the equal protection clause of the 14th amendment in their argument that aspiring (white) adoptive families are denied equal treatment when they are subject to ICWA procedures. In doing so, the plaintiffs intentionally aim right at the heart not only of ICWA but of federal Indian law as a whole. At the heart of federal Indian law is the notion that tribal nations are political entities, that is, polities with a right to self-determination. This collective status both predates the US and has been affirmed time and time again as a parallel space of political authority in both US and international law.

To be sure, the very conceit that Indigenous peoples must submit to state practices of recognition is itself colonial and fundamentally unjust because it gives the colonizing society the right to define the parameters of Indigenous nationhood, political status, and identity. Yet, however unjust is the routine subjection of Indigenous societies to decisions in US courts, the “courts of the conqueror,” tribal sovereignty as constitutional legal doctrine and enactment of the right of Indigenous peoples to self-determination is nevertheless fundamental to the existing edifice of Indigenous power within US public law. Such laws are themselves the result of Native nations’ continual struggles against recurrent practices of colonial land theft, child removal to boarding schools and now foster homes, invasion, and forced migration. As a consequence, questioning the sovereignty of Native Nations in the form of placement preferences for Native families and tribes as a form of reverse “racial discrimination” is also a way of destroying the entire political and legal force of sovereignty as a way of connecting Indigenous peoples’ individual and collective freedoms and protections against colonial domination. It is to replace the paradigms of sovereignty and jurisdiction that have emerged from struggles against the colonial state with a language of race that is, at best, ignorantly misplaced, and, at worst, a way of further perpetuating ongoing violence against Indigenous communities, families, and children.

The argument as presented by the Texas Attorney General also may sound familiar to those following the conservative Supreme Court’s longer term efforts to dismantle the rationale behind many other progressive policies aimed at even quite mild reforms of the white supremacist power structures that have long shaped who has access to basic dignity, voice, and power in US “democracy” (the notable conservative exception on the Court being Justice Neil Gorsuch, who departed from his colleagues in both decisions). In the last two federal Indian law cases that went before the Supreme Court, McGirt v. Oklahoma (2020) and Oklahoma v. Castro Huerta (2022), Chief Justice Roberts followed this script in issuing opinions—the first as voice for the minority, the second for the majority—that likewise disavow the basic facts of the history of colonial conquest and Indigenous peoples’ resistance that today form the constitutional basis of Indigenous sovereignty.

These Indian law cases also run parallel to 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder case, in which Roberts wrote for the 5-4 majority that struck down as unconstitutional the preclearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act. Immediately after the decision, Alabama jumped at the opportunity and began to systematically disenfranchise Black voters. As is the case with ICWA, the reason that the conservative legal movement does not like preclearance is not because it is not needed anymore. Rather, it is precisely because these measures work, however insufficiently. They are band-aids for exercising institutional counter-power against dominant actors who are quite willing to exercise antidemocratic means to hold and secure power.

The claims of the plaintiffs in Brackeen parallel the points of emphasis in Justice Roberts’ majority opinion in Holder: a condescending acknowledgment of targeted corrective policies and laws as only appropriate in our tragic past; the absurd claim that acknowledging the existence of racial and colonial domination reinforces it; the claim that states would no longer pursue these same violations if they were not forced to stop by federal law; the notion that congress is overstepping its constitutional authority over states, regardless of the practical consequences for the already marginalized; and, finally, the idea that practices that aim to secure the powers and rights of marginalized peoples are instances of “reverse racism.”

However, as is so often the case with attacks on Indigenous rights and sovereignty, Brackeen has both everything and nothing at all to do with the direct mission of upholding colonial domination over Indigenous peoples. On one hand, it is all about colonialism, insofar as dismantling a law expressly designed to protect the rights and interests of Indigenous societies and children is a straightforward instance of how the US is a society founded on and still invested in the removal, conquest, and territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples. The argument that (potential) adoptive parents suffer discrimination all at once misreads ICWA (which alerts tribes to cases, gives mere preference, and asserts initial tribal jurisdiction), disavows that Indigenous peoples are a political, not a racial, group, and deflects any confrontation with the unavoidable reality that these practices are genocidal and do quite directly individualized harm to Native children removed from extended family networks.

On the other hand, the entire effort here among those pursuing this case is to use ICWA as a way to gain a wedge in to dismantle the basic principles of federal Indian law. Why dismantle federal Indian law? The plaintiffs’ case really represents convergence of all sorts of other unabashed political and economic interests expressed in the guise of law. Specifically, it is not a surprise that the states (Texas, and in prior iterations of the case in lower courts, Indiana and Louisiana) who have signed on to challenge ICWA have the smallest Indigenous populations. As Cherokee journalist Rebecca Nagle and her team document in the second season of their This Land podcast, there are a number of basically venal interests at work in the backdrop of this case.

Among these are conservative attorneys general who want to take power back from Congress (as they want to do with federal elections), adoption attorneys who already find legal ways around ICWA but would like a more direct route to Indian children, and the conservative law firm Gibson Dunn, which boasts a client list of key players in the oil and casino industry that have a rather obvious stake in dismantling their competitors in tribal gaming and collective land ownership and land reclamation by tribes. In short, these are parties simply taking advantage of the systemic vulnerabilities of Indigenous peoples, families, and children to further advance their own power. Here, colonial domination of Indigenous peoples, children, and families become the stepping stone to accumulate power. Needless to say, these ulterior motives have absolutely nothing to do with a genuine commitment to the equal treatment of non-Indian adoptive parents, let alone any concern with the welfare of Indigenous children.

The hearing and verdict in Brackeen awaits, but what is clear is that it will not be the last of the deeply cynical efforts to dismantle federal Indian law.

To conclude, we ought not to think of Indigenous sovereignty as a claim of collective over individual rights. The exception argument makes Indigenous sovereignty seem antithetical to some ahistorical, indeed, counterfactual framework called “liberalism” that is best instantiated by the US nation-state. Somewhat ironically, such an argument tends to imply that tribal sovereignty is “illiberal” but in ways that can be justified, with suitable modifications, to meet the standards of universalizable liberal principles.

Practically speaking, the exception argument plays right into the hands of those who are constantly forum-shopping to find courts that will dismantle that “exception” like the petitioners in Brackeen. Those petitioners cynically pose the interests of Indigenous children against those of Native nations, by advancing an entirely decontextualized and empirically misleading account of the hypothetical burdens placed on white adoptive families (and, very secondarily, on Indigenous children being mistreated by their families and nations). What I have illustrated here is that even the sometimes well-meaning defense of Indigenous sovereignty as (justified) exception tends to reinforce the bad faith, untenable claims that animate contemporary anti-Indigenous racism, most especially the idea that tribal governments are exceptions to liberal norms.

Instead, Indigenous sovereignty is a norm, one that arises from the experiences Indigenous peoples have had of insisting upon the very practical connections between individual and collective rights in the face of degrading and harmful practices like family policing. In this way, ICWA is a necessary, albeit insufficient, law that stems from a real, ongoing, and pressing set of violations of the well-being of families, children, and communities. Indeed, the real story here is that the well-being, freedom, and care of and for Indigenous children, parents, and families are really secured only insofar as Indigenous communities themselves are able to exercise enough power to prioritize keeping families together and healthy. Stripping away the very flimsy façade of arguments against Indigenous sovereignty shows how parochial, shallow, and opportunistic those arguments are when contrasted with the genuinely existential and emancipatory aspirations that underlie laws like ICWA.

Indigenous sovereignty articulates how the rights and well-being of Indigenous individuals are created, connected to, and ultimately entangled with the collective as a subject claiming freedom against colonial domination, in the context of an unrelentingly colonial state whereby various forms of structural violence are visited upon those individuals, including children. Indigenous sovereignty is a practice of freedom and of (re)making of networks of care and kinship against parochial forms of state repression and oppression.

David Myer Temin is Assistant Professor of Political Science and faculty in Native American Studies at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor and is the author of Remapping Sovereignty: Decolonization and Self-Determination in North American Indigenous Political Thought (University of Chicago Press, 2023).