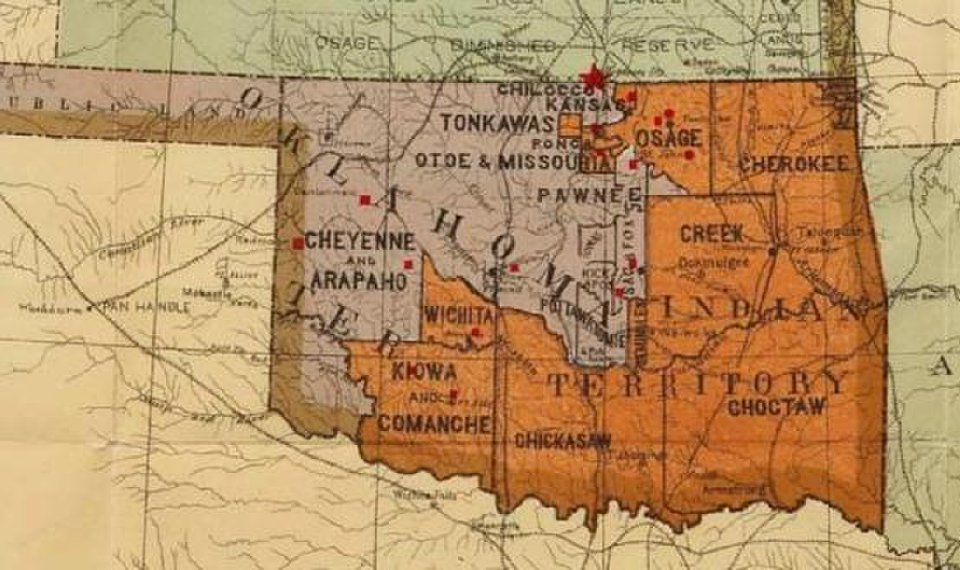

Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the majority in McGirt v. Oklahoma, answers the question “whether the land [previous] treaties promised [the Muscogee (Creek) Nation] remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law” with a resounding “yes.” The 5-4 decision reaffirms the Creek Nation’s sovereignty over lands long practically-administrated by the State of Oklahoma, including most of the City of Tulsa. Taken on its own, this decision goes far in halting the retreat of tribal sovereignty against the march of United States’ jurisdictional dominion in a war of attrition. Viewed in the context of 2020, McGirt v. Oklahoma is part of a larger struggle to, as Gorsuch writes, “hold the government to its word.” This effort involves not only keeping old promises, but also dismantling paternalistic systems designed to gradually replace tribal authority with state or federal authority.

By Treaty, in 1832, the Creek Nation ceded all lands east of the Mississippi. In exchange:

The Creek country west of the Mississippi shall be solemnly guarantied to the Creek Indians, nor shall any State or Territory ever have a right to pass laws for the government of such Indians, but they shall be allowed to govern themselves, so far as may be compatible with the general jurisdiction which Congress may think proper to exercise over them.

Congress, Gorsuch argues, never said otherwise—this despite nearly two centuries of policies designed to restrict, coerce, allot, and terminate the peoples living there. That 1832 Treaty—amended by the Treaty of 1866—and land guarantee, remains legally binding on all parties.

As Chief Justice John Roberts warns in his dissent, one consequence of the ruling is that Oklahoma’s “ability to prosecute serious crimes will be hobbled and decades of past convictions could well be thrown out.” The thrust of the dissent rests upon the concern that the “Court has profoundly destabilized the governance of eastern Oklahoma,” creating uncertainty for state authority over Indian affairs. The Court’s decision will allow “thousands” of indigenous peoples like Jimcy McGirt—convicted of the molesting and raping a four-year-old—to “challenge their state court convictions.” The dissent, Gorsuch counters, “assures us… that the consequences will be ‘drastic precisely because they depart from… more than a century [of] settled understanding.’” If settled understanding, however, be founded upon a breach of the law, then such settled understanding has no place in the republic.

Roberts’ “settled understanding” bears further scrutiny. While, in this case, the concept does concern many years of governance in the State of Oklahoma, affecting millions of lives, it also rests upon an all-too-convenient truth in the eyes of the state: that tribal lands are best managed by Oklahoma. This “settled understanding” hardened over centuries spent perpetuating the idea that indigenous peoples could never use or govern their lands as well as United States officials. Georgia made a similar case in 1828, when it forcibly extended legal jurisdiction over Cherokee lands. The issue today is not unique to Oklahoma either; this idea has found a home in American institutions more broadly. Consider the altercation between state and tribal nations taking place in South Dakota.

To halt the march of COVID-19, two South Dakota tribes—The Cheyenne River and Oglala Sioux—established roadside checkpoints, monitoring the flow of traffic in and out of their lands. Governor Kristi Noem soon demanded their removal, threatened legal action, and appealed to the White House for aid in taking them down. For CRST Chairman Harold Frazier and Oglala Sioux President Julian Bear Runner, these checkpoints are about saving lives. For Governor Noem, this dispute is about setting precedent on who can block highways. Yet underlying both positions is a fundamental tension over sovereignty.

The implicit policy attitude that tribal governments may do as they please on their land, as long as the state does not disagree, stems from centuries of paternalism toward indigenous peoples. By paternalism, I mean a prevailing attitude—however intentioned—that US officials, not tribal members, know what’s best for tribal communities. Historically, what has been considered ‘best’ is most often in the immediate interest of the state, not the needs of the tribe. Indigenous peoples are left in the precarious position of having to anticipate the unspoken desires of the state or face consequences should the state disagree with tribal decisions.

In this case, Governor Noem’s March 23 Executive Order encouraged local governments generally, and tribes specifically, to “make their own decisions.” South Dakota is one of the few states that did not issue stay at home orders. Chairman Frazier and President Bear Runner, working with local and municipal leaders, concluded that none possessed the infrastructure to deal with massive COVID-19 outbreaks. Thus the checkpoints were born, out of an abundance of caution—a prime example of collaborative local government.

While tribal lawyers and South Dakota lawmakers debate the legality of the road checkpoints, it behooves us to remember that these tensions are often about sovereign power as much as they are about what’s legal. Several members of the South Dakota State Legislature, a bipartisan group, said as much in a letter to Governor Noem, stating that South Dakota does not have the authority to dictate tribal actions within a reservation. The same is true of the struggle in Oklahoma.

This situation in South Dakota highlights why open communication, understanding, and an active appreciation for compromise are essential for finding unity in diversity. As there has always been, there is an expectation gap between tribal nations and state governments. Tribal nations may expect to have—and have a right to—free reign over their territory to govern however they deem proper. State governments may expect tribal nations conform to implicit or unstated state guidelines in doing so. Inherent expectation gaps necessitate constant, active, explicit communication to avoid confusion and, in this case, lawsuits.

Understanding is also crucial—tribal governments were not founded on the same liberal principles as the American states. The nature of tribal government is exclusive—that is, membership is restricted, in many cases to those able to trace lineage to an ancestor listed on the Dawes Rolls. This exclusive model of citizenship conflicts with the modern American citizenship project, for which exclusive citizenship is anathema. Yet pluralism is part-and-parcel with the American notion of self. By denying tribes the opportunity to convey their own sense of self to the majority, we actively undermine the principle of pluralism. Open communication and understanding of each other’s founding principles, therefore, are essential. From truly understanding these differences, we may see the benefits each political tradition brings to the table.

The United States is structured in part around the idea that there is strength in diversity—our federal system, after all, permits states like South Dakota to avoid issuing stay at home orders, despite other states deciding otherwise. In a way, that same principle applies to tribal governments, whose decisions—like that of the Cheyenne River and Oglala Sioux to establish checkpoints—can offer insight into the multiple innovative ways governments could respond to COVID-19.

Remi Bald Eagle, intergovernmental coordinator for Cheyenne River, summed up their philosophy by saying that “You don’t lock the door once the wolf is in the room – you lock it before it gets in.” A report on May 14 stated that there were three confirmed cases of coronavirus in the Cheyenne River and Oglala Sioux populations combined. Their policy seems to have kept the wolf at bay. While the task at hand is not to evaluate the effectiveness of a specific COVID-19 response, the example shows how a diversity in perspectives can be a valuable tool for governing during crises.

Returning to the McGirt decision, Roberts and company fear that a decrease in Oklahoma’s authority over tribal members will lead to tribal nations reclaiming their sovereign power with a vengeance—and that convicted criminals will go free. “Ultimately,” in what Gorsuch calls a “self-defeating” argument, “Oklahoma fears that perhaps as much as half its land and roughly 1.8 million of its residents could wind up within Indian country.” The implication there is that Indian country will not treat them well and will fail in the execution of justice. The implication is that tribal nations would do to the states what the states have done to them if given the chance.

“Dire warnings,” however, “are just that, and not a license for us to disregard the law.” Congress can, of course, change the law when it desires to. But the Supreme Court reaffirmed what was already true, but not practiced, and exposed another system of paternalistic bias against tribal nations. Lawmakers and American citizens across the country have the opportunity to view this decision as either a loss of state authority or as an opening by which to transform Indian relations into something much more positive.

Anticipating the decision, Oklahoma and Creek authorities are already collaborating to ensure that criminal acts are found, tried, and prosecuted in a manner that ensures the continuation of justice. Locally, and on the front lines of policy implementation, as evidenced in Oklahoma and South Dakota, tribal and state/local authorities already have productive working relationships. Gorsuch and the Court stand poised to counter views hostile to tribal sovereignty by holding the government to its treaty promises, many of which—like the Cherokee ability to appoint Kim Teehee as delegate to Congress—are denied legitimate legal standing and then discarded as relics of the past. Gorsuch’s opinion gives hope that an America reeling from both COVID-19 and protests against racial injustice can find solace his words: “Unlawful acts, performed long enough and with sufficient vigor, are never enough to amend the law.”

Aaron Kushner is a Postdoc in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University. He is a project manager for the Living Repository of the Arizona Constitution Project and Associate Editor of Starting Points.