Amongst the general educated public in America, the eminent political theorist Hannah Arendt is probably best known for her concept of “the banality of evil,” which she discusses in her 1963 book about the trial of the Nazi war criminal, Adolf Eichmann. One indicator of just how famous the phrase “banality of evil” became is that Ronald Reagan invoked it in a 1985 speech to the European Parliament. Born in Germany in 1906, as a young woman, Arendt studied philosophy with two intellectual giants – namely, Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger. Arendt was Jewish, and in 1933, after the Nazis rose to power in Germany, she fled to Paris. In 1940, Arendt was sent to an internment camp in France where stateless Germans were being held. In 1941, she managed to emigrate to New York City. Arendt first became famous with the publication of her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism. She argued that both Nazism and Stalinism constituted a terrible new form of government that is distinct from past forms of tyranny insofar as totalitarian leaders seek to achieve what Arendt called “total domination.”

In recent years, as authoritarian governments have been on the rise in many parts of the world, public intellectuals and pundits have often turned to The Origins of Totalitarianism in an effort to better understand the dangers of – and the links between – populism and authoritarianism. One aspect of Arendt’s political thought that has not received much attention, though, is her interest in the concept of statesmanship. In other words, while Arendt’s works have often been referenced by contemporary authors who are concerned with the problem of authoritarian leadership, Arendt’s ideas on what makes for an excellent leader rather than a destructive one have been much less examined.

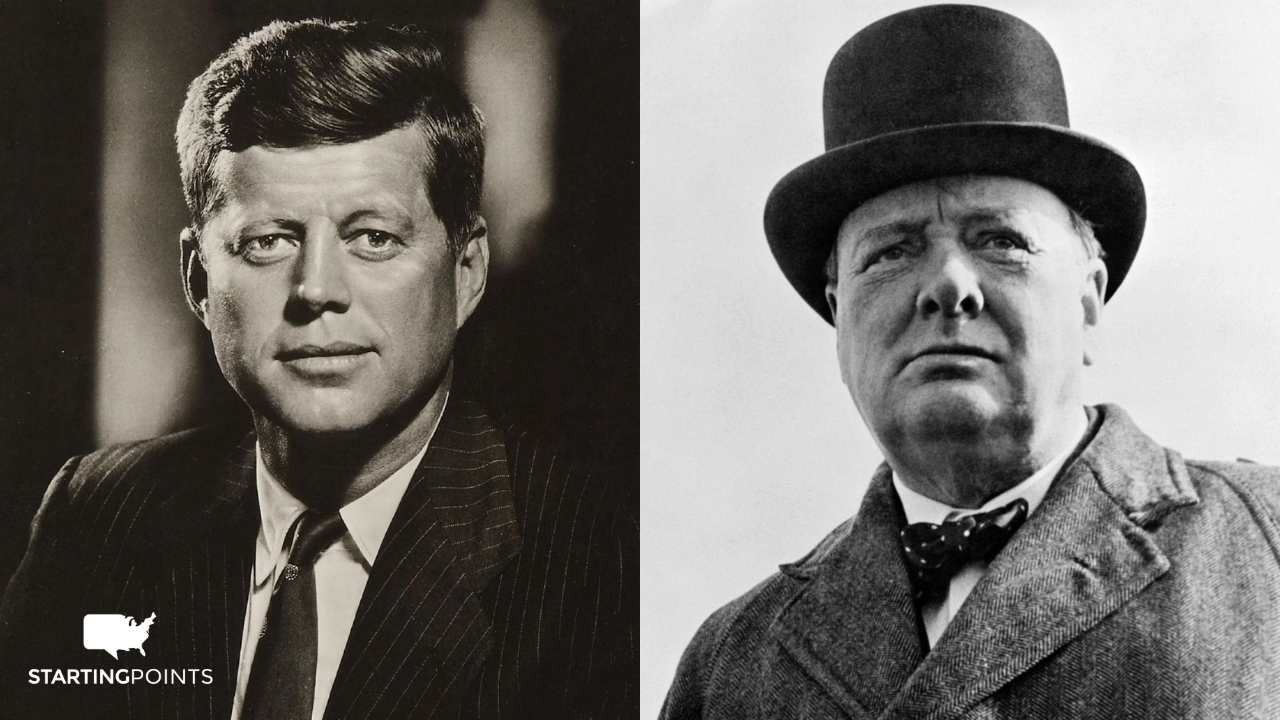

Granted, Arendt never engaged in a sustained or lengthy discussion of statesmanship. However, in a number of striking passages scattered throughout her writings, Arendt sketched out some very intriguing ideas regarding the qualities that great statesmen need to possess. My focus in this essay will be on Arendt’s ideas on Winston Churchill and John F. Kennedy, Jr., both of whom Arendt greatly admired. As we shall see, through her discussion of Churchill and Kennedy, Arendt provides us with an understanding of statesmanship that remains highly relevant for contemporary American politics.

In a 1965 lecture, Arendt called Winston Churchill “the greatest statesman thus far of our century.” What, though, were the attributes that led Churchill to be such an outstanding statesman? Arendt answers this question by writing that Churchill revealed “that whatever makes for greatness – nobility, dignity, steadfastness, and a kind of laughing courage – remains essentially the same throughout the centuries.” Certainly, the “dignity,” “steadfastness,” and “courage” that Churchill displayed in standing up to the Nazis and in rallying his nation against them have been widely admired. Arendt’s use of the word “nobility,” though, might give the reader pause. Did Arendt here mean to suggest that only those with an aristocratic background can be great statesmen?

Clearly, the answer to this question is no, for in her 1963 book, On Revolution, Arendt bemoaned the absence in modern America of “public spaces to which the people at large would have entrance and from which an elite could be selected, or rather, where it could select itself.” This kind of “elite” would differ from what she calls “the pre-modern elites based on wealth or birth” because it would consist of “those few from all walks of life who have a taste for public freedom and cannot be ‘happy’ without it.” According to Arendt, this kind of authentic elite was able to emerge through the councils that spontaneously and temporarily sprung up (until they were displaced by political parties) during both the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Arendt argued that a genuine political elite could also have been produced in America through Thomas Jefferson’s proposed “ward-system,” which was a never-realized plan to divide each of the nation’s counties into even smaller political units; through these local wards, every citizen would have the chance to become an active participant in government and to distinguish themselves in the political realm. Given Arendt’s belief that a genuine political “elite” of public-spirited citizens can and should be made up of people “from all walks of life,” it is likely that when she referred to Churchill’s “nobility” she had in mind a kind of grandeur of spirit that may be rare but is not exclusive to a particular social class.

Arendt suggested that the leaders who emerge out of a council-system of government are likely to possess what she calls “the qualities of the statesman or the political man,” which include “trustworthiness,” “personal integrity,” the “capacity of judgment,” and sometimes “physical courage.” Arendt also stressed that these qualities of the statesman are distinct from the qualities of an administrator or manager. One way to grasp Arendt’s point about the distinction between the qualities of the statesman, on the one hand, and the qualities of the manager or administrator, on the other, is to consider an extreme case – namely, that of Adolf Eichmann. In Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), Arendt writes that Eichmann found that, “There were two things he could do well, better than others: he could organize and he could negotiate.” Yet, insofar as Eichmann chose to put these administrative skills to evil purposes he showed that he was the very antithesis of a statesman. Surely, a person who possessed not only administrative skills but also the “capacity of judgment” could never have chosen to act in the way that Eichmann did.

As for Arendt’s claim that “trustworthiness” is a key quality of the statesman, one can find additional discussion of this point in her “Reflections on the 1960 National Conventions: Nixon vs. Kennedy.” In this piece, Arendt argues that it is useful for the citizenry to watch the televised convention speeches because “the screen brings into view those imponderables of character and personality which make us decide, not whether we agree or disagree with somebody, but whether we can trust him.”

By pointing out that the question of whether you agree with a candidate’s stated policies is quite distinct from the question of whether you trust the candidate, Arendt anticipates a memorable moment in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical, Hamilton. Late in the second act, after a tie in the Electoral College meant that it would be up to the House of Representatives to determine who would win the presidential election of 1800, Hamilton declares his support for Jefferson over Burr. But how could Hamilton possibly support Jefferson, given his opposition to the Virginian’s policies for so many years? Miranda’s Hamilton answers as follows: “I have never agreed with Jefferson once…./We have fought on like 75 different fronts…/But when all is said and all is done/Jefferson has beliefs; Burr has none.” While these are, of course, not Hamilton’s actual words, Hamilton did indeed often suggest that Burr lacked the virtue of trustworthiness. For example, in a letter from January of 1801, Hamilton wrote of Burr: “No Mortal can tell what his political principles are. He has talked all around the compass. …The truth seems to be that he has no plan but that of getting power by any means and keeping it by all means.” Taken together, Arendt, Miranda, and Hamilton suggest that a statesman who has a sincerely-held and consistent vision of how to achieve the common good can inspire a considerable degree of trust and respect even among those who fervently disagree with – and who seek to combat – that vision.

It is here worth observing that in recent years, it has not been uncommon for American conservatives to look back at Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a considerable degree of admiration, just as there are some liberals who have found a good deal to admire when assessing Ronald Reagan. How is it that liberals can admire, at least in certain respects, a conservative president (Reagan) and conservatives can admire a liberal president (FDR)? It seems likely that a part of the answer is that both Reagan and FDR are now widely seen to have possessed some of the attributes that Arendt mentions, including “trustworthiness,” “personal integrity,” “steadfastness,” and “a laughing courage.” Today, when American citizens choose whom to vote for, they should, of course, give a great deal of consideration to a candidate’s public policies; at the same time, it would behoove them to also consider, as Arendt highlighted, whether a candidate is someone whom they can trust to act in a principled manner, even when it takes courage to do so.

Arendt’s understanding of statesmanship is further revealed in her high praise of John F. Kennedy. In her “Reflections on the 1960 National Conventions,” Arendt wrote that in contrast to Richard Nixon, who “has modeled the image of himself on the virtues of the common man,” Kennedy “obviously strives for an image of statesmanship in all its grandeur, destined to recall Franklin D. Roosevelt, although actually modeled on and influenced by the other great statesman of our time, Winston Churchill.” Arendt asserted that Kennedy’s convention speech (which is now known as the “New Frontier” speech) was “by far the best speech of the conventions.” In defense of this claim, Arendt highlighted “the gusto with which [Kennedy] announced, ‘the problems are not all solved and the battles are not all won.’” Arendt also called attention to Kennedy’s “obvious contempt for ‘private comfort’” and to “his use of words such as ‘pride, courage, dedication,’ pitted against security, normalcy, mediocrity.” In short, Arendt found that Kennedy “believes in greatness,” whereas Nixon, in contrast, “would not have dared to ‘hold out the promise of more sacrifice instead of more security.’” Rather than call on the citizenry to make sacrifices in the pursuit of grand national achievements, Nixon instead presented himself, in Arendt’s view, as the embodiment “of the current Republican credo… that ‘to get ahead’ and to improve constantly one’s living standards is the quintessence of freedom.”

Arendt’s suggestion that statesmen should inspire citizens to work towards goals that are loftier than the pursuit of security and economic well-being is highly reminiscent of Alexis de Tocqueville’s ideas in Volume II of Democracy in America (1840). Tocqueville believed that the widespread “equality of conditions” that he observed in America would inevitably be coming to Europe as well. While the rise of equality could bring many benefits to humanity, one of the potential perils inherent in the march of equality, Tocqueville believed, was that it tended to make people excessively materialistic. He argued that during the aristocratic era of the past, social classes were fixed such that the wealthy took for granted that they would always be wealthy; at the same time, the poor in a sense also took their poverty for granted insofar as they had little hope of rising out of it. The result was that during the age of aristocracy, neither the rich nor poor were “preoccupied with physical comfort.” In contrast, in the new democratic era there is always a possibility of economic mobility (upward or downward), and this means that everyone now anxiously focuses their energies on gaining (or keeping) material wealth. In order to counterbalance a democratic people’s focus on wealth and “physical comfort,” Tocqueville suggests that the leaders of democratic societies “should sometimes give” the citizens “difficult and dangerous problems to face, to rouse ambition and give it a field of action.” As described by Arendt, Kennedy can be seen to exemplify precisely the kind of leadership that Tocqueville believed was needed, for Kennedy insisted, as Arendt noted, that “the problems are not all solved and the battles are not all won.”

What kinds of “difficult and dangerous problems,” as Tocqueville put it, did Kennedy call on Americans to face? The goal of sending a man to the moon (and safely bringing him back) could certainly be seen as one such dangerous and extremely ambitious task. As Kennedy put it in 1962, “We choose to go to the moon in this decade” and take on other challenges “not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills….” An even more important goal was announced by Kennedy in a televised address on June 11, 1963. On that evening, Kennedy finally insisted that civil rights was “a moral issue,” and he called on Congress to protect the right to vote and to abolish segregation in public accommodations and educational institutions. Noting that “these are matters which concern us all,” he exhorted all Americans to help create a society in which everyone is “afforded equal rights and equal opportunities.” Kennedy did not, of course, live to see either the moon landing or the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In calling for the nation to pursue these great national projects, though, Kennedy showed himself to be the kind of statesman that both Arendt and Tocqueville suggested was necessary.

Today, it is common for Americans to focus on economic issues when they are choosing their leaders. This focus was noted by the campaign advisor James Carville in 1992 when he famously declared: “It’s the economy, stupid.” To be sure, it is entirely appropriate – and absolutely necessary from an electoral perspective, as Carville pointed out – for political leaders to address economic concerns such as unemployment and inflation. Indeed, one danger inherent in Arendt’s critique of an excessive focus on “physical comfort” is that it can potentially lead to an overly dismissive attitude regarding the quite genuine economic challenges that many Americans – and especially working class Americans – are facing. The notion that economic issues are somehow “beneath” the concerns of the true statesman is an elitist idea that must be rejected. That said, there remains a great deal of value in Arendt’s suggestion that statesmen should seek to inspire the citizenry to pursue bold national goals that transcend economic concerns, at least some of the time. What are the specific grand goals that Americans should strive to collectively achieve today? The answer to this question is, of course, always going to be open to contestation in the political realm; it is a key task of the statesman, though, to try to forge a degree of consensus on this crucial question.

In a brief piece written after he was assassinated, Arendt wrote that Kennedy’s “words and actions displayed the highest virtues of the statesman – moderation and insight.” In an earlier essay on “The Crisis in Culture”, Arendt explained that by “insight” she meant “the ability to see things not only from one’s own point of view but in the perspective of all those who happen to be present.” Arendt noted Kennedy’s ability to see political issues from multiple perspectives when she wrote that, “He never lost sight of the thinking of his opponents, and so long as their position itself was not extreme… he did not attempt to rule it out, even though he might have to overrule it. It was in this spirit, which derived from his ability to grasp his opponents’ thinking, that he greeted the student demonstration which picketed the White House after he decided to resume nuclear testing.” Implicit in this passage is the idea that the virtue of “insight” (as defined by Arendt) can help to foster the virtue of “moderation”; specifically, if one is able to see an issue from the perspective of one’s political opponents, one is more likely to end up with a nuanced and complex understanding of the issue that may lead to a moderate position. In contrast, a one-sided understanding of an issue is more likely to yield an extremist position.

In today’s era of hyper-polarization, Arendt’s claim that a key virtue of the statesman is to understand the perspective of one’s opponents is as relevant as ever. As the author Bill Bishop has discussed, there is a good deal of evidence that Americans have in recent years been “sorting” themselves geographically into communities of like-minded people. In a similar vein, the scholar Cass Sunstein has called attention to the danger that in their digital lives, Americans may be exposed mostly to ideas that simply reinforce their pre-existing beliefs. As Bishop and Sunstein have each in their own way emphasized, a life lived in these kinds of geographic and digital “silos” might very well result in Americans becoming more extreme and more polarized. In this context, Arendt’s suggestion that Kennedy’s greatness stemmed in part from his ability to “grasp” and to engage with “the thinking of his opponents” has a great deal of resonance. For at a time when it is all too common for political partisans to demonize their opponents, American democracy could certainly benefit from having leaders who have the capacity to thoughtfully and respectfully consider opposing viewpoints on political issues.

I have here focused on three key components of Arendt’s understanding of statesmanship. First, Arendt suggested that statesmen must seek to gain the trust of citizens, including even those with whom they have political disagreements. Second, she believed that statesmen should try to inspire the citizenry to pursue grand national goals that at times transcend material concerns. Third, she argued that statesmen must strive to see political issues from multiple perspectives and thereby avoid extremism. As shown, each of these three points can be usefully applied to present-day American politics. In a 1964 interview, Arendt stated that she engaged in the process of writing not because she sought to be “influential,” but rather because she wanted “to understand.” In the 21st century, Arendt’s particular understanding of statesmanship still remains well worth our consideration. For while the fate of a democratic republic ultimately rests in the hands of the citizenry as a whole, it is surely also the case that democratic republics require outstanding leaders – especially during times of crisis – who can help to guide and to inspire their fellow citizens.

Brian Danoff is a professor of Political Science at Miami University. He received his PhD from Rutgers and has written extensively on American political thought and modern political theory throughout his career. He is the author of Why Moralize upon It? Democratic Education through American Literature and Film (Lexington Books, Lanham, MD, 2020) and Educating Democracy: Alexis de Tocqueville and Leadership in America (SUNY Press, Albany, NY, 2010).