Legal scholars spend a lot of time debating the proper way to interpret the Constitution. Political scientists study voting blocks on the Court or trends in judicial appointments. But to think about the future of constitutional government, we should give more attention to the ultimate authority behind the Constitution – “We the People,” as the Preamble calls us.

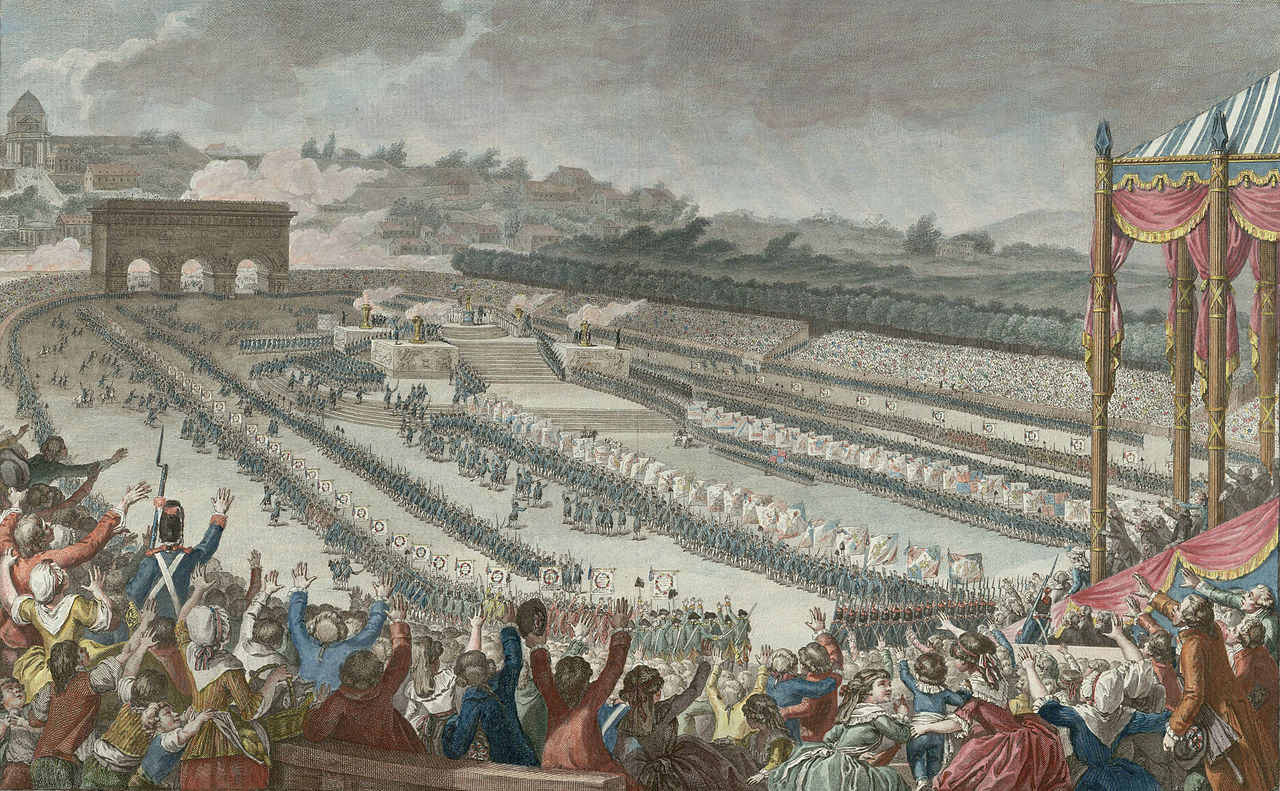

The Founders did not think all people were equally capable of sustaining constitutional government. At the outset of the French Revolution, for example, Alexander Hamilton wrote to his friend Lafayette, expressing a “foreboding of ill.” He warned, among other things, about the “vehement character” of the French people and their susceptibility to “philosophic politicians” and “speculatists” [sic] propounding doctrines not compatible with “the composition of your nation.”

Perhaps that sounds bigoted or chauvinistic. But self-styled progressives were also quick to say, during the administration of George W. Bush, that it was absurd to expect that the overthrow of Saddam Hussein would lead to “a Jeffersonian democracy in Iraq.” As it happens, Hamilton was proven right about the immediate course of the French Revolution, while opponents of the Iraq war were wrong about the durability of free debate and elected governments in Iraq. These are not isolated examples. Even in recent times, constitutional government has failed in Russia and Venezuela, but proven more enduring in many African and Asian countries where outsiders predicted a return to coups or chaos.

We should, therefore, not be dogmatic about the social and cultural prerequisites of constitutional government. We must acknowledge, however, that people in some conditions do find it hard to sustain a government with constitutional limits. Either way, we shouldn’t be smug about the prospects for constitutional government.

Social trends in contemporary America are warning signs for the prospects for constitutional government even here. I don’t mean that we will soon succumb to a terrible tyranny. Still, we should not be at all confident about maintaining our well-defined constitutional boundaries or the political stability they have provided us for so long.

The main problem we face is the degree of political polarization. Americans have always had differences. After all, we fought a terrible civil war in the Nineteenth Century. But after that upheaval, subsequent generations found it easier to work together – and postpone debate on issues where they could not agree. The political parties were diverse coalitions. Democrats and Republicans were as likely to disagree with fellow party-members as with adherents of the opposing party.

In recent decades, the parties have become more ideologically homogenous. Divisions between left and right on various issues – particularly contentious issues like abortion, gun control, and religious freedom – characterize the differences between the parties. This is not surprising. Left and right can now get news and opinion tailored to their own priorities on cable TV, on call-in radio programs, on web sites and Twitter feeds. People have been sorting themselves to neighborhoods, localities, even cities and states where their own views predominate.

Left and right don’t just differ in their own views but in their sense of what differences are acceptable. Current opinion surveys find that two thirds of Democrats think President Trump should be impeached while very few Republicans think so (and only a minority of self-described independents). But not only Democrats are angry. In one survey a few years ago, a near majority said they would be disturbed if a son or daughter married someone of the opposing party. That was a survey of Republicans in the Obama era. Differences have become personal and rancorous.

When political division becomes too intense, people think winning – or undermining the other side – must take priority over every other concern or commitment. In other countries, intense political conflict has often been the prelude to military coups (or other forms of authoritarian take over), which were welcomed by a substantial part of the population. Constitutional government requires loyalty to constitutional norms, above party. It’s hard to make that appeal when people are so focused on forestalling their opponents.

A second difficulty, related to the first: We seem to have less attachment to our common past – or rather, less willingness to view the American past as a common heritage. Young people know less about our past, which seems not to be well taught in schools. A 2018 survey asked native-born Americans to take a test of basic civic knowledge which immigrants must pass to gain citizenship. Barely twenty percent of Americans under 45 scored passing grades, while 80 percent of those over 65 did. Perhaps the young are less interested. A 2012 survey found some 80 percent of those in their late 60s or older felt being American was “very important” to their identity, but less than half of those under 35.

Disengagement from our roots may feed the current divide. On the left, critics depict the Constitution as the work of dead white males – or worse, of slave-holders of accommodators or slavery. Opposing them, fervid Trump supporters refuse to listen to complaints that the current president is falling below standards of conduct or decorum set by his predecessors. If everything is subordinated to the struggle against racism and oppression – or to “making America great again,” by pushing back on “the left” – it’s hard to get people to care about constitutional norms.

So Democratic candidates talk about abolishing the Electoral College or changing the size of the Supreme Court or overturning Supreme Court rulings on free speech – as if long-established practices deserve no regard. Trump supporters defend assertions of unilateral executive power – in building a wall or slapping down new tariffs – without any regard for established constitutional limits. The Federalist warned against frequent changes in constitutional arrangements, because only long-standing practices would earn the “veneration” without which “the wisest and freest government would not possess the requisite stability.” That sort of appeal does not carry much weight where everyone is concerned about winning now.

Finally, perhaps most tellingly, we have come to a point where much of the public readily accepts government dysfunction if that is the price to be paid for frustrating opponents. Congress cannot agree on even minimal steps to deal with the crisis of illegal immigration through our southern border. It cannot agree on minimal steps to deal with a tottering health insurance system, where current law requires companies to provide coverage to people who seek insurance only when gravely ill – and the law requires no one to pay premiums before that.

Congress cannot even face ruinous threats to programs that still mobilize broad support – in principle. Trustees of the Medicare Trust Fund warn it will become insolvent in less than a decade. The Social Security System will face the same fate in little more than a decade. Beyond that, interest payments on accumulated federal debt – allowed to mount without restraint through Democratic and Republican administrations alike since 2000 – will in a few years exceed annual expenditures on national defense. Congress is too divided even to talk about necessary reforms.

It’s easy to blame politicians but they respond to voters and their priorities. In today’s climate, it’s not easy to win election by promising, “Vote for me and I’ll work with the opposing party to find pragmatic legislative responses to common problems.”

The challenge for constitutional government is less dramatic than facing a riot in the streets, but still sobering: When the crisis can’t be ignored, Congress is less likely to forge its own compromise than to delegate broad authority to the executive to respond. Or perhaps the President will claim inherent powers to respond. We may forestall financial or security crises only by coming to see constitutional procedure as a dispensable ceremonial relic rather than a fundamental requisite of legitimate government.

Will courts maintain reliable checks? It is hard to be optimistic about that, especially when President Trump denounces unfavorable court rulings as the work of “Democrat judges” and Democrats promise to reconstitute the Supreme Court to deliver better results (as they see them). Even judges with clear constitutional convictions may flinch from confrontation with aroused politicians.

I don’t see an easy fix for these trends. If history is a guide, it takes a shared catastrophe to shake people from partisan rancor. Friends of constitutional government should do more to alleviate these partisan tensions and encourage their fellow Americans to focus on that which gives us common cause.

Jeremy A. Rabkin is Professor of Law at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University. This article is based on remarks given at the “We the People: Fidelity to the Constitution” conference on April 13, 2019, in Chicago, IL.