As several scholars, like Bernard Bailyn, Caroline Robbins, and Gordon Wood, have reminded us, a number of ideological influences have played a significant role in the creation of the American republic. Among them were two opposing concepts that were at the center of the Founders’ debate over the meaning of republicanism in America. One was steeped in a tradition going back to Greece and Rome; the other was the product of the late 17th century. In this essay, I will examine the core elements of classical republicanism and Lockean liberalism as well as the dynamic tension that existed between the two and why the latter became, by the end of the 18th century, the more dominant force in the development of the American republic.

Classical Republicanism

In the years leading up to the American Revolution, republicanism was most often defined in its classical sense through the works of Aristotle, Polybius, Cicero, Livy, Sallust and Tacitus, and later espoused by such political theorists as Machiavelli, Harrington, Sidney, Bolingbroke, Montesquieu and Rousseau. This version highlighted the ideal of a virtuous citizenry acting on behalf of the res publica and voluntarily setting aside self-interest. In his Politica, Aristotle asserts that humans realize their full potential as zoon politicon only when they actively participate in the affairs of the polis (vita activa) by doing what is necessary for the good of the state. Such virtue directed on behalf of the state was in no way related to Christian virtue, for it was overtly social in nature—a manifestation of homo politicus. Today we would label it patriotism.

Civic virtue was also central to Machiavelli’s political thought. It was he who, in both his Il Principe and Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio, revived the Aristotelian and Polybian ideal of the active citizen who did whatever was necessary for the good of the state. Most importantly, he focused on the image of the citizen warrior, ready to give his life in service to the state. This Machiavellian concept of a militia made up of citizens fully invested in the defense of the state was to become a cherished element in the Anglophone republican tradition as it was set in stark contrast to a standing army, which was seen by 18th century Whigs in both Britain and America as the tool of tyranny and an impediment to liberty.

In 17th century England, this Aristotelian-Polybian-Machiavellian concept of civic involvement was most notably taken up by James Harrington, whose The Commonwealth of Oceana had a profound impact on the political theory of John Adams. In equating virtue with ownership of real property (i. e. land), Harrington asserted that only a republic in which a majority of the people were freeholders could be stable, for possession of real property gave the citizen the incentive to follow the Aristotelian vita activa—it motivated them toward working for the betterment of the state. And in his influential Esprit des Lois, Montesquieu asserts that only such civic virtue can be relied on to serve as the underlying principle of a republic. John and Samuel Adams, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and Richard Henry Lee were among the many 18th century colonial leaders whose public and private writings highlighted this particular view of republicanism. Indeed, pre-Revolution literature trumpeted the fact that the Americans were the true defenders of a virtue-based, disinterested republicanism against the increasingly corrupt forces of the British Ministry and Parliament. Without virtue, Adams proclaimed, liberty could not be maintained.

Republicanism in this classical sense was rooted in the assumption that the people of any given state were a homogeneous body sharing the same experiences and holding the same values. Thus, what was beneficial for the general populace should be deemed beneficial for the individual. “The sacrifice of individual interests to the greater good of the whole,” writes Gordon Wood, “formed the essence of republicanism and comprehended for Americans the idealistic goal of the Revolution.” This assumption certainly lies at the heart of the 18th century British concept of virtual representation, which Edmund Burke and his fellow Whigs, as well as some notable Americans such as Noah Webster, strongly endorsed. As Burke expressed to the citizens of Bristol in 1774, once elected to Commons, he no longer was bound by local interests. Rather, the welfare of all Britain was to be his main concern: “Parliament is a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole, where, not local purposes, not local prejudices ought to guide, but the general good . . .” On the other hand, actual representation, which the vast majority of colonists emphatically defended by attacking taxation without representation, prioritized local interests over the common good, an early sign of a shift away from the primary focus of classical republicanism. Community instructions detailing how elected representatives were to vote on particular matters, such as the Braintree Instructions of 1765, were a prominent example of how localism came to dominate colonial, and later state, politics.

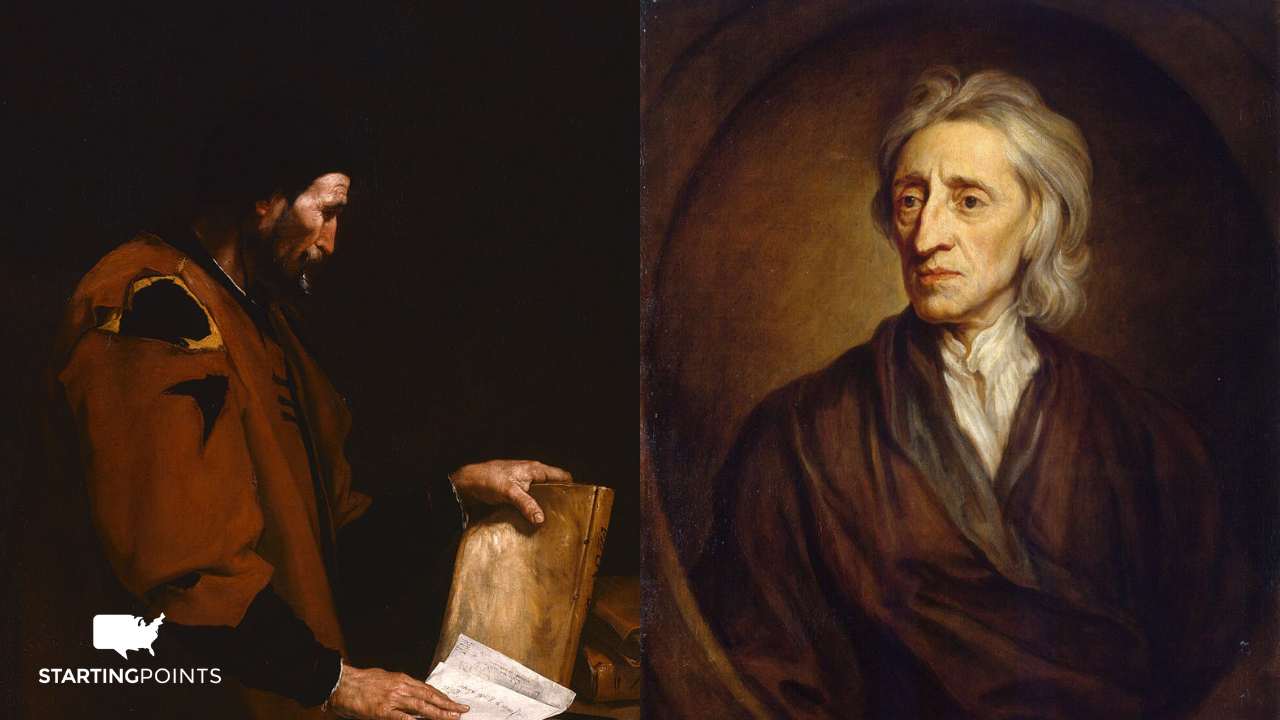

Lockean Liberalism

In his Second Treatise of Government, John Locke argues that government originated as the result of a compact entered into by individuals intent on safeguarding private property: “The great and chief End therefore, of Mens uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property.” While Locke’s emphasis on property as the underlying factor for the creation of government had a certain Harringtonian echo, his idea of property was not limited to land.

Indeed, Locke emphasized the importance of mobile property (i. e. money and credit) in the development of society away from subsistence to growth economy similarly to Scottish philosophers David Hume, Adam Smith, and Adam Ferguson. Commerce, the trading of valuable materials such as precious metals for essential goods, allowed energetic and resourceful individuals to emerge as powerful members of a society which no longer saw all men as equal in property and prestige. It was thus necessary to ensure that there was protection for these individuals’ rights and property lest greedy but less dynamic persons attempt to undermine the fruits of their labor. In the commercial world of Locke, the res publica existed to foster the life, liberty, and property of the individual, who had the freedom to pursue his particular goals even when they conflicted with those of the majority. This was diametrically opposed to the classical model, in which the individual’s self-fulfillment came from working on behalf of the state.

Could Classical Republicanism Remain a Viable Concept in an Increasingly Commercial World?

It was during the Revolution and post-Revolution years of the 1780s that it became apparent to many Founders that self-interest was, after all, an integral part of American society. Greed and selfishness seemed to replace disinterestedness as prevailing characteristics of 18th century America. Merchants took advantage of the war, often dealing with the enemy, to accumulate fortunes while, after the war, newly established state legislatures, catering to the special interests of their constituents, passed laws that favored debtors vis a vis creditors, thus encroaching on certain individuals’ right to property while supporting one faction’s concerns. The classical model of republicanism no longer appeared viable to many of the founding generation. Gordon Wood described this new unifying principle as “an agglomeration of hostile individuals coming together for their mutual benefit,” rather than a people united in interest. John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison in particular came to the conclusion that civic virtue could no longer be held up as an essential foundation for an expansive republic. Lockean liberalism, with its focus on individual rights and the protection of not only real but also mobile property, became the principal catalyst in the development of the fledgling American republic. In his brilliant Federalist No. 10 essay, Madison acknowledges the omnipresent existence of special interest factions and thus focuses on the best way to control them. Hamilton’s first major paper as secretary of the treasury provided a blueprint for tying the interests of the wealthy to the new government. Adams’s Discourses on Davila discusses how honors and offices, and not civic virtue, can bind the ambitious natural aristocracy to the government.

In the early years of the American republic, the clash between Hamiltonian Federalists and Jeffersonians is best understood as an ideological battle over what 18th century republicanism meant. Jefferson, at least publicly, continued to embrace the language of classical republicanism through the 1790s. He praised the republican yeoman whom he saw as the indispensable foundation of a new state that would counter the corrupt powers of Europe. Jefferson’s stated faith in the virtuous common man committed to the res publica was directly opposed to the more cynical view of Hamilton, who asserted that, left to their own devices, men would unhesitatingly choose what was in their best interests. It was thus necessary for government to find a way to bind together the interest of the individual, especially the moneyed class, and the welfare of the state. This was the underlying rationale behind his bold funding program of 1790.

While certainly not an advocate of the Hamiltonian program, Adams, who in his early years had expressed unbridled faith in his countrymen’s virtue, did come to share the New Yorker’s more pragmatic view of Americans. The motivation behind his ill-fated title campaign in the spring of 1789 was not a monarchist’s zeal to imitate European courts, as his opponents charged, but an effort to use titles and honors to attract the best people to the federal government. Like Hamilton, Adams realized that men were willing to work for the common good only if their self-interests were satisfied. As he noted most explicitly in his Discourses on Davila, the quest for distinction is the driving force behind an individual’s actions.

This dramatic confrontation between what one might call a realistic versus an idealistic conception of republicanism reached its apex in the 1790s with the American response to the French Revolution. The philosophes’ embracing of equality and fraternity, their expressed desire to eradicate all vestiges of hierarchy, and their commitment to a constitution that established a unicameral legislature pledged to the general will were met with warm applause by Jeffersonians. They saw in the French Revolution the logical culmination of America’s own quest for an ideal republic based on common, rather than individual, goals. Hamiltonians, on the other hand, were less enthusiastic, warning that the French experiment was destined to fail, given the philosophes’ failure to take into consideration man’s tendency to act out of self-interest. Accepting Locke’s premise that humans came together to form government out of a desire to protect personal property, they rejected as unnatural any attempt to redistribute wealth in the name of egalitarianism. While not a Hamiltonian, John Adams was the most vocal American opponent of the French Revolution. In his 32 essays under the title Discourses on Davila, Adams drives home the point that man is controlled by his quest for distinction and thus cannot be expected to act in an altruistic way, as classical republicanism and the philosophes assumed. Rather, the well-ordered republic must find ways to utilize one’s self-interest for the good of the society at large. It was this realization of the fundamental flaws of an idealized republican society and of the need to create a government that took into account human nature with all of its warts that J.G.A. Pocock famously referred to as America’s “Machiavellian moment.”

With the election of Jefferson and the repudiation of the Federalists in 1800, classical republicanism, with its focus on sacrifice and the common good and its distaste for overt luxury and greed, appeared to briefly reassert itself. The unilateral acquisition of Louisiana in 1803 was viewed by Jefferson as an important step in America’s realization of its “Manifest Destiny,” a way to ensure the proliferation of republican yeomen throughout North America. And the Embargo Act of 1808 hearkened back to the halcyon years leading up to the Revolution when virtuous citizens willingly sacrificed their interests for the good of the state.

Nevertheless, there was no turning back to the classical republicanism espoused by Aristotle, Polybius, Machiavelli, and their Enlightenment followers. The financial system established by Hamilton in the 1790s as well as the rise of manufacturing, again under the impetus of the Hamiltonian program, created, in the early 19th century, a society that could never completely return to the idealistic republican way of life lauded by classical authors and Jeffersonians.

What one notes in post-Revolution America is a radically new way of viewing the relationship of men and society. The rights of the individual and the interests of society were now seen as being distinct and at times in conflict. Despite Americans’ willingness to sacrifice their own interests for the common good in times of crisis, the Lockean commitment to the happiness and well-being of the individual within a pluralistic society was to prevail, and it has remained a point of emphasis in American political discourse for the better part of the republic’s history.