In Common Good Constitutionalism, Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule seeks to accomplish for the whole of American constitutional law what the landmark Dobbs opinion delivered to the nearly fifty-year abortion regime of Roe v. Wade—a dramatic reversal. Unlike the devoted ranks of the FedSoc crowd, however, Prof. Vermeule is not angling for the triumph of originalist jurisprudence. Rather, he argues for the recovery of a deeper tradition: not the retrieval of original meanings, but a return to the original meaning of law itself. Common Good Constitutionalism is a vigorous, thoughtful, and brisk sketch of how the classical legal tradition—a “rich stew” of Roman and canon law, European and Anglo-American sources—might inform, and does in fact undergird, Vermeule argues, the American constitutional order.

The classical legal tradition is grounded in a universal architecture of law, most famously explained by Thomas Aquinas, who saw the natural law as an imprint of divine reason on the created order. Natural law provides the moral structure and justification of all legitimate human law. At a foundational level, this requires four things: a law must be (1) a rule of reason, (2) made for the common good, (3) by governing authority, and (4) promulgated (i.e., publicized). The core of Vermeule’s argument concerns the first two points: law’s rational orientation to the common good.

The common good is a notoriously complex and often ambiguous concept in the history of legal and political thought, and Vermeule provides a necessary synthesis oriented, he notes, to the interpretive work of a lawyer. Concisely put, “The common good is unitary and indivisible, not an aggregation of individual utilities. In its temporal aspect, it represents the highest felicity or happiness of the whole political community, which is also the highest good of the individuals comprising the community.” (7) Although he is careful to clarify that the common good contributes to the flourishing of human persons (rather than the state as such, for example), the individual’s highest good is to be a part of the unitary common good. The core content of this good, he argues, are conditions of peace, justice, and abundance, which are furthered by the magistrate’s traditional authority to regulate for health, safety, and morals—“legislating morality” in light of a “substantive vision of the good.” (37) Where these police powers ultimately reside is a key part of the account Vermeule gives of the common good in the American context.

By Vermeule’s lights, the great failure of modern American constitutionalism is the rejection of this classical framework. Despite the federal structure of the U.S. Constitution that vests only specifically enumerated powers in the national government, Vermeule contends that early American statesmen and jurists always recognized a natural law foundation of the constitutional order. This means that teleological principles like the common good do not depend on specific textual justification for their constitutional validity. Likewise, exercise of authority for the common good is grounded more in the “nature and purpose of government” (41) than in specific textual provisions. While Vermeule allows that a public authority’s responsibility for the common good is often constrained by the remit of his office, such limitations are secondary to the deeper logic of just government.

Fidelity to the Constitution, therefore, requires application of its unchanging principles to the vicissitudes of political history. Perhaps most significantly, this leads Vermeule to a relatively swift desertion of the Constitution’s federal structure in favor of a de facto national police power. He concludes that the massive expansion of U.S. federal power has served the common good of peace, justice, and prosperity in increasingly complex social, economic, and political circumstances. Adherence to the moral teleology of the constitution—if not its structural particularities—fulfilled the purpose of good government and was thus a valid legal development.

Vermeule distinguishes his constitutional teleology from, on the one hand, the supposed moral progress of “living constitutionalism,” and on the other, the legal positivism of originalist jurisprudence. Given his enthusiasm for Ronald Dworkin, it is often difficult to distinguish Vermeule’s common good constitutionalism from progressive jurisprudence on anything other than moral grounds. But he argues that his classical theory maintains consistency of fundamental principles across time, while progressive jurisprudence defenestrates outmoded moral norms in favor of an ever-expanding individual autonomy. Originalism, on the other hand, has proved to be an illusion, Vermeule contends, both denying the moral foundations of law while frequently basing decisions on a tacit political morality. Justice Gorsuch’s infamous Bostock opinion is the prime example of what Vermeule has in mind: a highly abstract textual argument driven by an implicit moral account.

There is, of course, much more that could be said about Vermeule’s book, but this provides at least a sketch of the central thrust of the work. In what follows, I want to briefly consider two ways that Vermeule’s limited account of the common good inhibits the persuasiveness of key parts of his argument. In the first place, his account of the common good leaves out an essential feature of the classical formulation, namely, the participation of citizens in debate about the meaning of justice and the good. Secondly, he gives insufficient attention to the common good as an ordered whole, comprised of personal and social goods that have integrity apart from fulfillment in the common good.

As to the first point, the very essence of politics, Aristotle argued, arises from discussion among citizens about the nature of the just and the good. Many necessary conditions of life (defense, utilities, practical coordination, and so forth) are extrinsic benefits of the common good, but discussion and debate about the true requirements of justice are inherent to human rationality and intrinsic to the association itself. It is, therefore, eminent among the values of the common good—and necessary to any plausible claim of preeminence made on its behalf. This is true even in republics, where citizens are not often immediately involved in deciding political questions. It is also descriptive of politics across time, given that a community’s pursuit of justice unfolds generationally. Moreover, as Michael Pakaluk has argued, achieving agreement on these matters is essential to the classical understanding of “peace” as a core desideratum of the common good. Thus, when Aquinas talks in De Regno about the life of virtue in a multitude, he has in mind this kind of shared pursuit among citizens of the meaning of justice and human goodness.

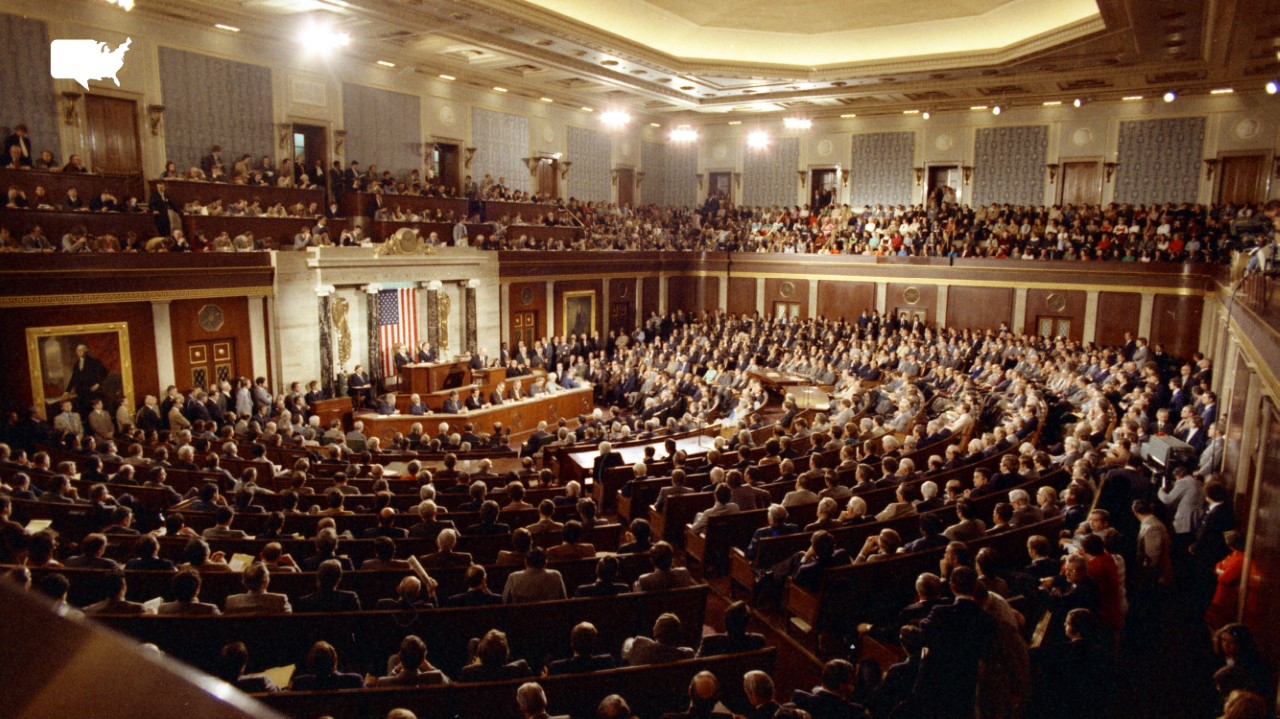

In the American context, of course, political deliberation was integrated with structures of representative government. Nevertheless, the common good retained a basic participatory significance. This was, in fact, essential to the debates among the Federalists and Anti-Federalists over the proposed constitutional structure. As the Anti-Federalist, “Centinel,” contended, “A republican or free government, can only exist where the body of the people are virtuous…and their sense or opinion is the criterion of every public measure.” Likewise, Brutus argued that representatives were obliged to “know the minds” and “speak the sentiments” of their constituents as they deliberated the common good. Of course, the Federalists disagreed, but not entirely, and the constitutional structure that arose out of compromise fused features of classical republicanism with institutions of consolidated power.

These ideas are, no doubt, very familiar to Professor Vermeule, but their absence from his argument weakens it considerably. He moves much too quickly to conclude that de facto federal police powers are constitutionally valid because, despite structural changes, they preserve the constitutional common good of peace, justice, and abundance. Granted, he does claim that political participation in states like Texas, California, and New York are not meaningfully different for individual citizens than in national politics. This makes reasonable sense if one thinks only of population size, but it becomes highly contestable if one also considers geographical proximity and regional differences. These considerations were, in fact, of tremendous importance to the Anti-Federalists, and one need only consider recent abortion politics to realize that their concern with local sentiments, customs, and interests is still relevant today. As Yuval Levin has argued, it may only be in a return to the federal structure of the constitution that America can successfully navigate the deep moral, cultural, economic, and political differences that fracture our country. American citizens need more and better ways to debate the profound issues that divide us; we need to recapture this vital feature of the classical common good. Because Vermeule begins with an essentially truncated account of the common good, he elides key issues in his analysis of American constitutionalism and misses important ways that a recovery of the common good can revitalize our politics.

The second way Vermeule’s account of the common good is deficient is in its relationship to liberty and rights. Here again, the problem is not so much in what he says about the common good as in what he doesn’t say. The main aim of his theory, he explains, is “to assure that the ruler has both the authority and duty to rule well”—this, over against “the liberal goal of maximizing individual autonomy or minimizing abuse of power.” (37) Empowering government to protect and promote the common good is not at odds with individual rights, Vermeule contends, because those rights “are always already grounded in and justified by what is due to each person and to the community.” (127) The law must always promote human flourishing, but the common good is an intrinsic and indispensable part of that flourishing. Indeed, as he repeatedly notes, it is “the highest good for individuals as such.” (14) Thus, “On the classical conception, ‘liberty’ is no mere power of arbitrary choice, but the faculty of choosing the common good.” (39)

As a rejoinder to the “hypertrophied” liberty of progressive constitutionalism, Vermeule offers a helpful corrective. Yet, what it means to call the common good the “highest good,” and to direct other goods to that end, are complicated issues in classical political thought. Famously, Aristotle identified the polis as a complete community because it possessed everything necessary—material, social, cultural, spiritual—for the good life. He recognized, of course, that the political common good is not the only common good necessary to human flourishing: friends, families, businesses, etc. all have common goods of their own. Yet, despite his profound understanding of various social goods, the good of the polis ultimately subsumes the rest in Aristotle’s thought. Individual goods and civil society are instrumental to the life of the polis.

From a Christian perspective, Aquinas makes subtle but decisive revisions to Aristotelian theory. For our purposes, two points are crucial: first, the political community exists as an ordered whole, and second, in personal and social life there is a class of “private goods” that cannot be justly directed to the political common good. The first idea simply means that the polis is a community of communities; its unity is one of organization, rather than integration. Thus, the parts of ordered wholes (both individuals and basic associations) have functions and purposes distinct from and not reducible to the goal of the larger whole. The meaning of the second point quickly follows: political authority must not assimilate the distinct goods of private life to the common good of the city. Aquinas illustrates this by arguing that whereas the law may command a citizen to exercise courage in going to war, it may not require him to show courage in defense of a friend. Friendship is a private good that cannot be justly made to serve political ends. Likewise, apropos Aristotle’s Politics, it would be unjust for the state to coopt the bonds of familial affection for the purposes of civic education. Despite the centrality of the common good, as M.S. Kempshall notes, Aquinas is consistently reluctant to ascribe “perfection” (or completeness) to the political common good. Instead, he affirms, “Man is not ordained to the body politic according to all that he is and has.” (ST I-II, 21.4.3)

This fuller account of the structure and limitations of the common good entails a more robust role for liberty and rights in classical legal thought than Vermeule is inclined to acknowledge. There is a multiplicity of personal goods (religious, moral, marital, etc.) and common goods (friends, families, churches, etc.) with natural ends, obligations—and thus rights—distinct from the common good of political society. Certainly persons and basic communities contribute to the political whole and flourish as part of it, but they are also loci of natural goodness not justly ordered to the political common good. Their dignity and justification derive from the same source as the common good: the natural law. In this vein, James Wilson explained the origin of natural liberty in his lectures on law,

Nature has implanted in man the desire of his own happiness; she has inspired him with many tender affections towards others, especially in the near relations of life; she has endowed him with intellectual and with active powers; she has furnished him with a natural impulse to exercise his powers for his own happiness, and the happiness of those, for whom he entertains such tender affections. If all this be true, the undeniable consequence is, that he has a right to exert those powers for the accomplishment of those purposes, in such a manner, and upon such objects, as his inclination and judgment shall direct; provided he does no injury to others; and provided some publick interests do not demand his labours. This right is natural liberty.

Wilson sees liberty as deriving from the capacities and goods that nature directs us to, but again, these goods possess natures, obligations, and rights distinct from, and not justly ordered to, the political common good. A just constitutional order is obliged by the natural law not only to exercise authority for the common good, but to ensure that these natural liberties are allowed to flourish.

While Vermeule allows room in his theory for liberty and natural rights, he consistently overstates their subordination to state authority and the political common good. For example, “On the classical conception,” he writes, “‘liberty’ is no mere power of arbitrary choice, but the faculty of choosing the common good.” (39) In fact, as I have argued, on the classical model, “liberty” will often choose natural goods only indirectly related to the common good. And government is obligated to protect citizens’ natural rights to do so. Or elsewhere, Vermeule argues, “Rights, properly understood, are always ordered to the common good and that common good is itself the highest individual interest.” (167) Statements like this, aside from important qualifications, are from a perspective informed by Aquinas and founders like James Wilson, simply in error.

Nevertheless, it is important not to overstate the imbalance of Vermeule’s theory toward political authority and the political common good. In this respect, his discussion of the subsidiary function of government is probably most relevant. This discussion incorporates his rejection of federalism, which I have already critiqued, but it also affirms that “subsidiary corporations of all types [families, etc.], have legitimate roles in an overall scheme for the promotion of the common good, and in that sense they are owed a duty of justice by the highest public authority not to be unnecessarily disrupted in the performance of those roles.” (164) He also affirms that when state intervention does occur it should be “exceptional” and ordered to the restoration of the appropriate natural function. This is reassuring, but only partially so. Vermeule entrusts the “highest public authority” with virtually unchecked (i.e., subject to weak judicial review) prudential authority to decide when a subsidiary institution has failed, what intervention is required, for what duration, and so forth. I leave it to readers of this provocative and lively book to decide for themselves if Professor Vermeule has sufficiently acknowledged and shielded the natural liberties of citizens and civil society. For my part, he has not.

Matthew D. Wright is Associate Professor of Government in the Torrey Honors College at Biola University. He is the author of A Vindication of Politics: On the Common Good and Human Flourishing. He thanks his colleague, Laurie Wilson, for directing him to the passage from James Wilson quoted in this review.