Teaching college students today about the significance of the American principles of freedom, equality, and constitutionalism is an uphill battle against the rise of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) at the expense of the humanities and social sciences, the bureaucratization of the classroom with its plethora of non-pedagogical mandates, and — perhaps most difficult of all — the intellectual climate of woke ideology that pervades the classroom. For teachers who profess a traditional understanding of the American founding and ideals, these obstacles may seem insurmountable. The problem is this: How can one teach American principles in a non-partisan and non-ideological manner in today’s academic environment?

To answer this question, we must first remember that college teaching is fundamentally about open inquiry rather than indoctrination, whether from the ideological left or right. Teaching is not about “the battle of ideas” in the hope that one set will prevail over another. Instead, teaching is the attempt to cultivate a sense of wonder in students by turning their souls toward what is enduring in our culture, regime, and civilization. Socrates called this turning of the soul periagoge where one experiences a wondrous conversion to pursue truth. Teaching therefore is not the reception and memorization of doctrine or dogma, but the embodiment of wonder to discover what is true, beautiful, and good in a community of teacher and students.

Second, we must recall that teaching transpires in a specific context of personalities with a unique set of desires, fears, and passions that need to be addressed and directed towards lasting principles and ideals. Teaching is not about decontextualized best practices that the contemporary pedagogical literature proclaims. The prevalence of this type of teaching is manifested most recently in fears that artificial intelligence will replace the professor. But these fears are unfounded because teaching is not an abstract exercise that can be implemented anywhere to anyone at any time. Rather, teaching at its best is tailored to a particular person to reach to his or her existential core to cultivate the experience of wonder. The interaction between teacher and student is a world of specificity unique to both parties, each needing to learn the wishes, ambitions, and hopes of the other in their joint quest to know the truth.

Third, teaching is both liberal and civic in its purpose. Liberal in the sense of studying subjects for their own sake so students can truly “free,” allowing students to reflect upon who they are and what their purpose in life is. Freed from the demands of utility and necessity, students engaged in liberal education can connect to what authentically makes them human beings. However, this freedom is not absolute — it does not offer students the tools to reinvent themselves to whatever they wish to be — because they are part of a larger tradition and members of a specific community. That is, students require civic education to make them good citizens. Civic education is especially important in democracies where citizens need to be informed and actively engaged. Democratic citizens are expected to question and critically examine the political doctrines they have learned in order to make the necessary adjustments that circumstances or principles demand in their regimes.

These two traditions of education — liberal and civic — can come into conflict with each other. Paradoxically the biggest threat to civic education often has stemmed from the state where instead of teaching students to question and examine political doctrines, they are indoctrinated into what they should believe. A genuine exploration of say, what constitutes American citizenship or what the Constitution means, is replaced by progressive or conservative propaganda. Hence, the need for liberal education to free students from these utilitarian concerns and point them to look outside a particular regime for sources of knowledge that may benefit the state. For example, the abolishment of slavery and racial segregation in America was not derived from civic education, which in some states reinforced these unjust practices, but a liberal one that looked to the Enlightenment ideals and Christian faith. By looking outside the regime, Americans were able to make the changes necessary for the country to be more just and true to its founding principles.

These two poles of human life — the pursuit of free intellectual inquiry and demands of political life — are not always reconcilable with each other. But this tension between liberal and civic education is beneficial, for neither the contemplation of truth transpires in a vacuum nor does the state have a monopoly over civic knowledge. As stated earlier, the teaching of enduring principles takes place in a specific context in a particular community for a student to understand them. And civic education demands students look outside their particular communities for the intellectual resources to improve their regimes. To have a robust citizenry, civic education is required; to have a flourishing human being, liberal education is crucial.

Periagoge and the Great Books

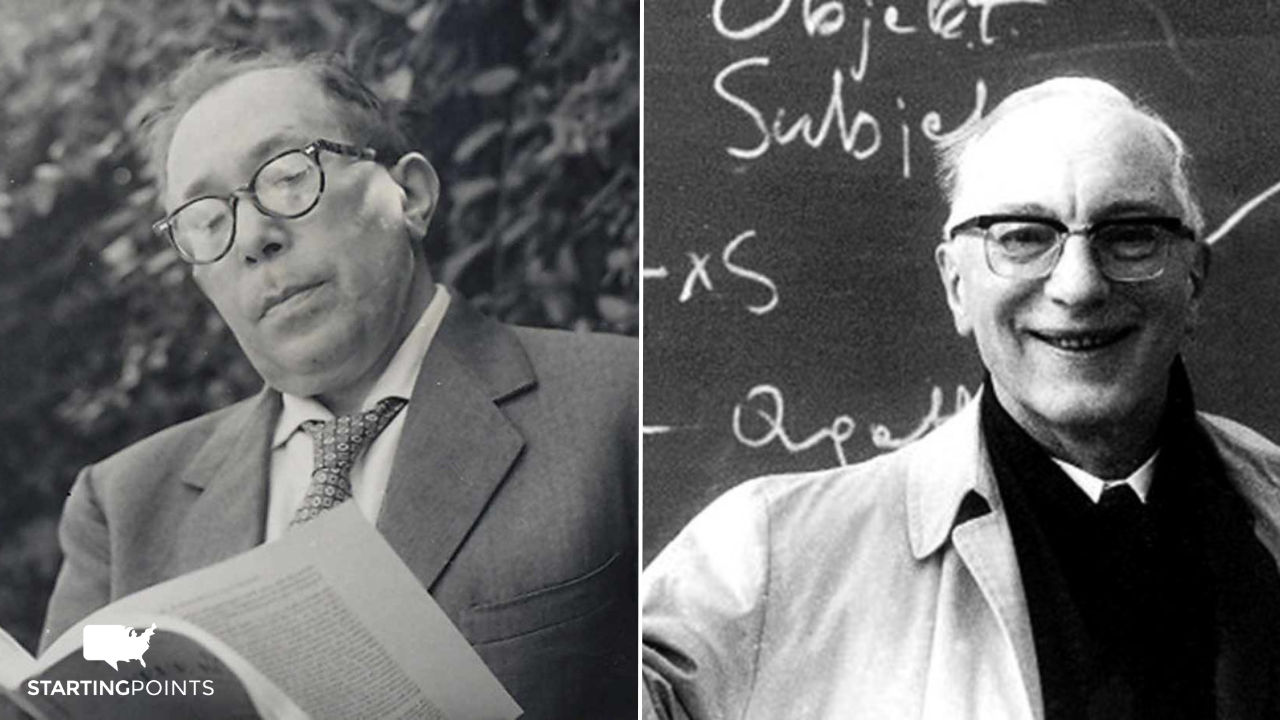

Two teachers who embodied these ideals were Eric Voegelin and Leo Strauss. Each portrayal of these thinkers as teachers are drawn from Teaching in an Age of Ideology, where Voegelin and Strauss are seen to live a life of the mind in action in their encounter with students. As teachers, Voegelin and Strauss sought truth rather than dispense dogma so both teacher and student could explore what it meant to be a good human being and a good citizen.

Eric Voegelin (1901-85) was an Austrian-American political philosopher whose best known works are New Science of Politics (1952) and his five-volume study of civilizations, Order and History (1956-87). He spent his early career at the University of Vienna but had to emigrate to the United States for published works critical of Nazi race ideology. He taught at Louisiana State University (1942-58) and later spent his career at the University of Munich and at the Hoover Institute at Stanford University.

Voegelin’s understanding of teaching drew directly from Plato’s description of it as the “art of periagoge”: the turning of the person from focusing on transient and temporal goods to eternal and permanent ones. Periagoge was less a religious or mystical conversion rather than a heightened awareness and openness to all reality that emanates from the true, the beautiful, and the good. The teacher’s role was to help turn the student’s soul to these things, although the teacher cannot do this for the student. The student alone must accomplish this task for him- or herself.

As a teacher Voegelin began with a student’s common sense — his experiences of the common world and the ability to reflect upon them — in order to lead the student to a type of reasoning that was clear of ideological thinking and to an attitude of intellectual humility that recognized a complete understanding of reality was impossible. Ideologues like Marx claimed that such knowledge was possible and thus adopted a posture of mastery instead of humility. By contrast, Voegelin believed that humans would always have an imperfect understanding of reality and therefore they always would be questioners, asking the question why.

For Voegelin, this underlying but incessant existential disquiet of the why, the doubting and desiring for something more than oneself, was a form of erotic restlessness which moved students to the true, the beautiful, and the good. By his mastery of complex material that was communicated extemporaneously and clearly, Voegelin was able to awaken this restlessness in his students. However, this passionate restlessness can never be satisfied: humans live in a state of permanent imperfection and consequently will always remain searchers for the truth.

Teaching therefore was not the insertion and playback of knowledge by students but rather the calling forth of passion within their souls. It was the cultivation of desire to see reality in all its dimensions for oneself. Of course, this entails risk, for students may mistake relativism for the true, nihilism for the beautiful, and ideology for the good. And the benefits of success were not apparent to the modern mind that demanded absolute certainty or a culture characterized by consumption and production. Yet, for Voegelin, this was the nature of the human condition. The student desired to step outside of his or her state of uncertainty and the teacher showed the student that it is a condition not from which to escape but instead to embrace, for the true, the beautiful, and the good are what humans long for in their lives.

Voegelin’s great rival and counterpart was Leo Strauss (1899-1973), an émigré from Germany, driven into exile in the 1930s because he was a Jew. Strauss received his doctorate at the University of Hamburg and taught at several places before settling down at the University of Chicago where he taught several students who achieved subsequent success in the American academy. As a teacher, Strauss was a staunch defender of liberal education, specifically of the Great Books, because the studying of the great minds would push students into thinking and contemplating the truth.

In this spirit, Strauss never turned away anyone from his seminars, which often were filled beyond capacity. Strauss taught only one text — whether a Platonic dialogue, a treatise by Nietzsche, or an essay by Kant — and ran his seminars in a hybrid Germanic-American style with students reading their papers followed by on spot commentary by Strauss who offered gentle but firm criticism. After this exercise, Strauss would turn to a systemic treatment of the assigned reading for that day, although he also would engage in a more American discussion centered format.

For Strauss, the great obstacle to liberal education was the conception of philosophy not as a path to the true, the beautiful, and the good but rather as an instrument of power and a type of technology to advance non-moral ends. This reconceptualization of philosophy transpired with the rise and dominance of modern science with positivist values and specialization of knowledge. It led humanity into a wasted landscape where a vision of the common good was absent. For Strauss, this was the crisis of our times.

Liberal education was a possible antidote to the narrowness of specialization and aimlessness of positivism. The Great Books were particularly adept at both broadening and deepening students’ perspectives in an age of science and democracy. This was ultimately the value of such an education, as Strauss himself knew, warning students of any delusions that they could derive any practical utility from studying the Great Books. Instead of utility, students learned the true, the beautiful, and the good; and by learning about them, students in turn would find dignity in themselves and in others.

Elements of Good Teaching

In spite of their different teaching styles, both Voegelin and Strauss were incarnations of the search for truth and conveyed this search in an accessible language to their students. Obscurity, ambiguity, equivocalness was shunned for clarity, precision, and transparency. The clarity of their language not only revealed a luminous intelligibility in the examination of texts but also a thinking devoid of ideological propaganda that has since characterized the contemporary university classroom. As a model of both clear thinking and speaking, Voegelin and Strauss sought to replace ideological dogma and doctrine with genuine thinking and intellectual humility.

If lucidity was required for good teaching, then trusting one’s student was even more critical, for without trusting students to make decisions for themselves, the teacher was merely passing down ideological dogma rather than pushing them onto a quest of questioning for the truth. Recognizing that ideology did the opposite — infantilizing students instead of having them think for themselves — Voegelin and Strauss trusted that their students would eventually find the true, the beautiful, and the good, and learn how to incorporate them into their own lives.

Both Voegelin and Strauss make appeals to the experiences of students as a starting point in their education. Instead of portraying themselves as masters of ancient and hidden knowledge or gurus of enlightenment, these teachers asked students to reflect upon their own experiences as a reference point to validate the claims made by the thinkers they were studying. Students consequently became aware — and motivated — to see why they were pursuing the true, the beautiful, and the good. And once this realization sank in, students then became willing to be guided towards theoretical reasoning about these matters.

Finally, intellectual humility was crucial for Voegelin and Strauss to be successful teachers. While they were deeply committed to what they were teaching, both Voegelin and Strauss balanced their own beliefs against the absolute certainty that characterizes ideologues. This balancing act between firmly held convictions and a vulnerability to be proven wrong was needed then — and now — to combat a climate of ideological indoctrination. The reason why Voegelin and Strauss had their convictions was because they were willing to risk them — willing to be proven wrong. Their authenticity came from their humility in testing their beliefs every time they entered the classroom semester after semester.

Broadening and opening students’ souls rather than narrowing and constricting them was the goal of Voegelin and Strauss. For all teaching — all good teaching — is not an abstract activity that is typical of ideological thinking but a particular act between teacher and student. It cannot be replicated in slogans and posturing; in fact, it cannot be replicated ever, for every act of teaching is a new act created and lost once transpired. If ideological thinking is based on the memorization and recitation of dogma, then genuine teaching is rooted in wonder, trust, and hope that students will mature on their own. As Voegelin and Strauss have shown, genuine teaching is a risk that rests on a prayer that the true, the beautiful, and the good will reveal itself, if ever so briefly, in the exchange between teacher and student.

Lee Trepanier is a political science professor and chair within the Howard College of Arts and Sciences at Samford University. He is the author and editor of more than 20 books, including The College Lecture Today: An Interdisciplinary Defense for the Contemporary University and Eric Voegelin’s Asian Political Thought.