“Providence has not created the human race either entirely independent or perfectly slave. It traces, it is true, a fatal circle around each man that he cannot leave; but within its vast limits man is powerful and free; so too with peoples.” Thus mused Alexis de Tocqueville in the closing pages of his magnum opus, Democracy in America. In many ways, it was the aim, not just of that peerless book, but of that peerless man, to forestall the contraction of that fatal circle so that people(s) might remain powerful and free.

Tocqueville’s impetus for doing so must be understood in light of the unique historical period during which his life transpired (for presumably at all times that fatal circle exists, contracting in some eras, expanding in others). That period signaled a turning point in, if not the cleavage of, history—between a dying aristocratic past and an inescapable democratic future. As a matter of circumstance, Tocqueville—born soon after the French Revolution to an aristocratic family that had been decimated by it—belonged to both worlds; as a matter of disposition, he belonged to neither.

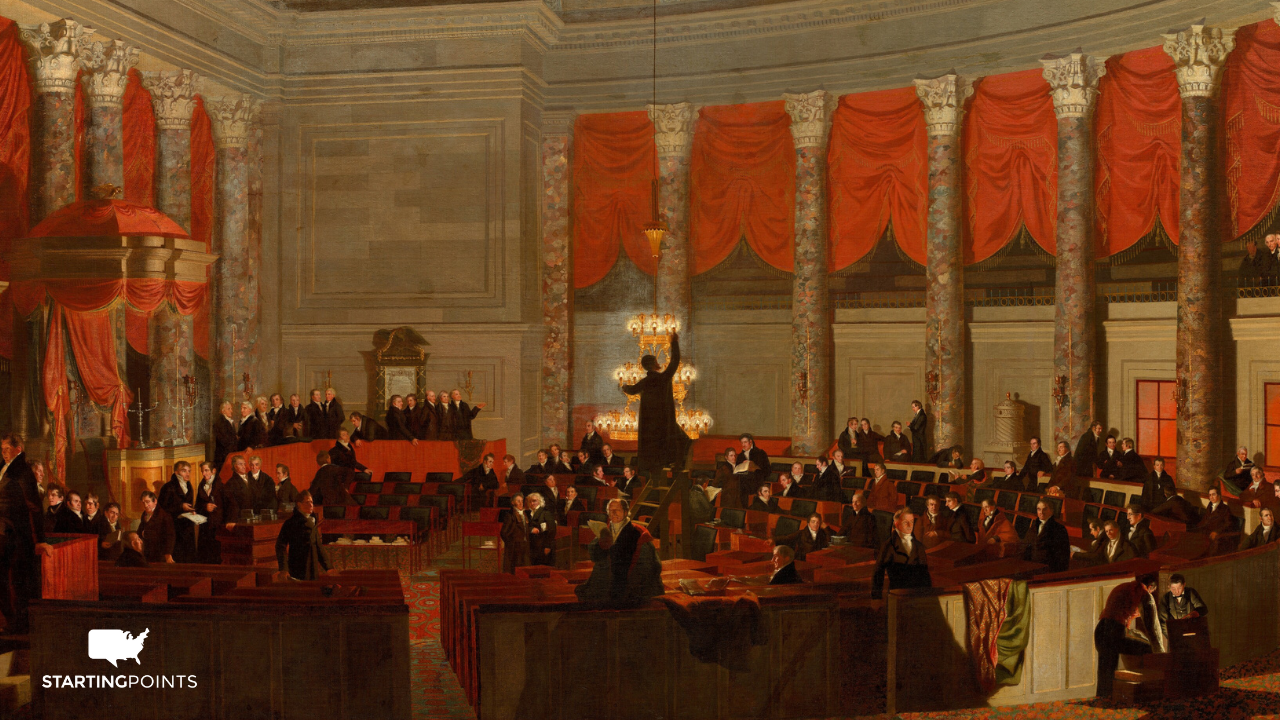

To better comprehend the character of the democratic age and the human type that populated it, Tocqueville traveled to America, on the grounds that it was there that the democratic revolution had advanced furthest. To paraphrase Lincoln Steffens, Tocqueville went to the New World to see the future and see if it works. What he found there was cause for both admiration and lamentation. What the young Frenchman admired, perhaps above all else, was the ability of the American people to prosper without the support of government, a reality that contrasted sharply with that of his own people, whose dependence on a central authority was entrenched and enduring. In Jacksonian America, Jackson’s own penchant for aggrandizement notwithstanding, the national government was weak, its reach patently limited—in both theory and fact. This arrangement lent itself to the preservation and exercise of the very quality that Tocqueville feared would become endangered in the democratic future: freedom. Of course, the absence of government alone was not enough to promote such a favorable outcome, at least not for an advanced or civilized people. Rather, what was required was the confluence of a number of features, ones that happened to be providentially harmonized in America (rendering the fledgling nation so exceptional in Tocqueville’s mind). These included the art of self-government, which the Americans, owing to their isolation from their mother country, had been invited, if not obligated to perfect, lest they perish; a federal republic that dispersed power between a national government firmly delimited by a written constitution and state and local governments that were much closer to the people and much more involved in governing their day-to-day lives; the art of association, which allowed individuals, who on their own would be piddling and powerless (a pitfall that, as a matter of course, riddles democratic times), to band together for a common cause and effect great deeds; and the role of religion, which sustained in man a spirit of sublimity that the trivial concerns and material pleasures endemic to democracy conspire to snuff out.

Tocqueville’s discovery of America fostered in him a sense of hope that humanity might be able to navigate the interminable seas of democracy upon which it had been cast without ultimately floundering. But for Tocqueville, that hope always remained tenuous at best. The features that contributed so effectively to America’s success and functioned as barricades against the democratic torrents that imperiled all peoples in the age of democracy could not simply be transplanted. They arose from unique historical circumstances, rooted in the customs of a discrete people who had the exceedingly good fortune to be born democratic. To ask a people long dependent on a central state, such as the French were, to govern themselves, would be a prelude to their ruin, not their success—a verity history had already demonstrated dispositively. There are some arts that can be cultivated readily; the art of self-government is not among them.

The deeper source of dread for Tocqueville was that the dangers that inhered in democracy were not completely remedied by the aforementioned provisions, so much as palliated; and that what was needed to keep those dangers in check was a degree of discipline that was repugnant to the very spirit those palliatives served to moderate. To appreciate where Tocqueville is coming from, it is necessary to apprehend what constitutes the defining aspect of the age of democracy: equality. This may appear an odd if not naïve postulation to those who occupy the twenty-first century, in view of the glaring inequalities that litter democratic lands. But the equality of which Tocqueville speaks is not the sort of equality of outcomes that socialists, of whom Tocqueville was unstintingly critical, promise to bring about. Rather, it is an equality of conditions or equality in principle that permits one to speak of a common humanity, wherein each member of it possesses an intrinsic and equivalent worth; the sort of principle that furnishes the foundation for human rights, which are a fixed feature of the present day and were effectively nonexistent in earlier ones. In pre-democratic times, in the age of aristocracy, it was as though there were separate humanities; different kinds of people, and not a single humankind to which all people belonged. This sentiment, so foreign and offensive to democratic sensibilities, is wonderfully illustrated by Tocqueville who recounts that according to Voltaire’s secretary, “Mme Duchatelet… felt no embarrassment at undressing in front of her servants, not considering it really proven that valets are men.” Today, proof is no longer needed to establish which species valets belong to, if ever it was.

Tocqueville forever remained profoundly ambivalent about the value of equality, perhaps all the more so because its inevitability was, in his eyes, bright as day. On the one hand, he maintained that a world predicated on equality was in principle more just: it would be a world of softened mores and extended opportunity and increased prosperity, which, by promoting the well-being of His children en masse, could not but be more pleasing to man’s divine progenitor. On the other hand, the spirit of equality had a potentially leveling effect that would isolate people from one another, unleash man’s baser appetites, and prove inimical to the striving for, let alone the attainment of, lasting greatness and distinction.

It was this insatiable thirst for equality that haunted Tocqueville’s thoughts and clouded his vision of the future, for it constituted the gravest peril to that inestimable good he persistently endeavored to perpetuate: liberty. As Tocqueville memorably put it, democratic peoples are inclined to prefer equality in servitude to inequality in freedom. This inclination is manifest in the twin forms of despotism that uniquely menace the age of democracy: tyranny of the majority and what Tocqueville called soft or mild despotism (despotisme doux). The former is the logical and arithmetical result of democratization. When distinctions between man and man of the sort that had prevailed in earlier days have been done away with, what follows is that no person or group of persons enjoys greater weight or authority than any other. Everyone is fit to be his or her own authority. The result is that wisdom or enlightenment will obtain wherever the greatest number of individuals happen to be of a like mind, since in a world of equal minds, two is better than one. In this way, the empire of the majority becomes absolute, because there is nothing outside it to resist or disabuse it. Those who dare to do so are punished, not with “the coarse instruments that tyranny formerly employed” (e.g. chains and executioners), but with shame and ostracism. While this form of tyranny can materialize in brutish fashion (the enslavement of African Americans would be an egregious example), the real threat is more nuanced and, one might say, immaterial. It does not constrain the body so much as it does the mind. Political correctness, which stifles the speech and thought of democratic peoples by barring from discussion topics that are eminently fit for it exemplifies this form of democratic tyranny, and furthermore substantiates Tocqueville’s observation that he did “not know any country where, in general, less independence of mind and genuine freedom of discussion reign than in America.”

The other form of democratic despotism, mild or soft despotism, is arguably the more subtle and foreboding form. It looms large in the final part of Democracy in America and colors Tocqueville’s outlook more considerably. It is not an antithetical or competing form of despotism, but a remarkably symbiotic one. Whereas majoritarian tyranny stems from the popular will or sovereignty of the people, soft despotism is an outgrowth of the central state, though it too is rooted in the will of the people, which is what makes it so subtle and pernicious. This form of despotism has no analogue in the annals of history. Traditionally, despotisms tended to be characterized by their severity and savagery, but in its democratic guise, despotism is gentle and solicitous. The state does not seek to brutalize and victimize its people, but to manage and care for them. It regulates the people’s lives more and more and does so in their common interests. In doing so, it makes life less burdensome and more convenient. It is precisely this solicitude that renders this new form of despotism so insidious. In its old form, despotism was not agreeable; nobody, save for those who wielded power, really desired it. But that is emphatically what mild despotism is—agreeable and desirable. But the convenience and comfort it affords do not make it any less despotic, and as with all despotisms—hard and soft alike—the result is the loss of freedom.

Tocqueville was no fatalist. He maintained that in spite of these dangers, freedom could be preserved in the age of democracy. But he was not exactly sanguine about the prospects. As indicated above, many of the measures that might help to impede or temper these forms of despotism were not readily replicable. But even where they were established, they remained precarious. Ironically, the democratic march of history points towards despotism. A movement that liberated people from the arbitrary chains of social class and the imperious rule of monarchs, lords, and the like, leads them to a state of despotism more absolute, albeit more mild, than any that has existed heretofore. What compounds this irony is that the servitude of the people would be of their own doing. In extolling equality above freedom, they willingly progress along the path to serfdom, which will bring them to a central authority beneath which all will be equal and none will be free.

Like a number of sages before him (e.g., Plato, Seneca, Machiavelli, etc.) Tocqueville entered the world of politics. The maker of theories aspired to become a policymaker. And as with many of those sages, Tocqueville turned out to be better suited for theorizing than for politicking. Tocqueville enjoyed some political success, having secured elected office (evidently being well supported by his constituents who reelected him) and been appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs (the highest post he would attain). But an independence of spirit that was instrumental to his literary success proved disadvantageous in politics. The futility of his foray into politics might be neatly encapsulated in France’s short-lived 1848 Constitution, which he had a hand in drafting and, thanks in large part to his efforts, incorporated some features of the US Constitution. Thirty eight months after going into effect, it was repealed, following the coup of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon III).

France’s return to a second Napoleonic empire prompted Tocqueville to abandon politics and return to writing. In doing so, he solidified a place of prominence in the pantheon of political thinkers with a book the greatness of which rivals Democracy in America, even if its renown pales in comparison. The Old Regime and the Revolution initially had been conceived as a work on Napoleon; or more broadly, as a work that would reveal how empire could reemerge so readily in the country that was home to the most seismic democratic revolution the world had ever known. But in investigating this matter, Tocqueville discovered that the road to empire had not been cleared by Napoleon, but stretched much further back into France’s ancient regime. What emerged from years of meticulous archival research and his wonderfully penetrating and original mind was the very same bête noire that bedeviled his reflections on America: centralization. That was the ultimate undoing of the ancient regime. It was the underlying reason why the revolution broke out where it did and why a monarchy, that had endured for centuries, collapsed overnight.

Tocqueville argued that unbeknownst to its own people—those on top and those below—France had been rotting from within for centuries. In every healthy aristocracy, there are symbiotic ties that unite all members of society—from the loftiest of princes to the lowliest of paupers—in a great chain of being. In this rigidly stratified world, reciprocity is the order of the day. Peasants labor for nobles whose freedom from toil is integral to their own nobility. In turn, nobles care for peasants that dwell within their domains, protecting them from outside dangers and providing for them in their hours of need. Such duties validated the privileges of the nobility in the eyes of those they lord over. What happened in France, beginning most notably with Louis XIV, was that the ties that kept society together began to unravel, as Paris arrogated to itself more power, depriving in the process the nobility of theirs. The result was that the nobility preserved its privileges while shedding the obligations that had legitimated them. Moreover, the people became more and more dependent on a central authority to which they had no meaningful attachments. All this accounts for why the democratic revolution, which had been advancing steadily across the Western world, erupted so suddenly and violently in France. An aristocratic order had been delegitimized by the machinations of a central state, which in turn promised more than it could deliver. The grievances and ire of the people, which had been brewing for some time, boiled over in 1789, so that all those judged to have wronged the people—the monarchy, the nobility, the clergy, the reactionaries—were pitilessly crushed. Because those bonds of reciprocity had been severed long ago, there were no defenders of the old order (save for in isolated places (e.g., Vendee)), so that the monarchy and ancient regime with it folded like a house of cards. To Tocqueville’s deeper point, having been so long dependent on a central authority, the people of France did not know what to do with the liberty they had procured, which is why the Revolution so precipitately devolved into the Reign of Terror and why a decade after beheading their once beloved king (Louis XVI), the French willingly bowed before an emperor (Napoleon I) possessed of a power far more plenary than what their king had ever enjoyed.

Tocqueville’s writings, from his first work to his last, serve as a warning to those who are predestined for democracy. It is a testament to his magnanimity that he was able to perceive both the virtues and vices of democracy when partisans on each side of the aisle could see only one or the other. With the age of aristocracy consigned to the dust heap of history, only partisans of democracy remain. Humanity’s fate, then, lies in the hands of a tyrannical majority that is conveniently blind to the dangers inherent in the political order that their reign presupposes. In view of this, Tocqueville’s musings not only remain as relevant as ever, but arguably are more important than ever. For all those committed to resisting the contraction of that fatal circle, perhaps there is no thinker more indispensable than Tocqueville.

David A. Eisenberg is the Associate Professor of Political Science at Eureka College, winner of Eureka College’s 2023 Helen Cleaver Distinguished Teaching Award, and the author of Nietzsche and Tocqueville on the Democratization of Humanity (Lexington Books, 2022).