Last month, Politico released a draft of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The opinion, authored by Samuel Alito, affirms that the Court – short of an unexpected revision or vote switch – will soon wholly overturn Roe v. Wade. Per the draft, “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start.”

Roe is a half-century old precedent prohibiting restrictions on abortion prior to fetal viability. The Court rested abortion access on an implied fundamental right to privacy implicit in the Constitution. This doctrine undergirds access to abortion, contraceptives, same-sex intimacy, same-sex marriage, and interracial marriage.

While the Dobbs opinion calls for deferring abortion regulation to “the people’s elected representatives,” Justice Alito’s judicial opinion creates a new, nationwide abortion regime. Political scientists have long claimed that un-elected Supreme Court justices will not overrule electoral majorities. The appointment of justices by popularly elected senators and presidents ostensibly tethers the Court to national electoral majorities. Robert Dahl famously noted that Supreme Court decisions affirm the will of “lawmaking majorities” in Congress and the electorate, albeit sometimes with a lag, thanks to justices’ life tenure and slow turnover.

But recently, the bond between the federal courts and electoral majorities has frayed. The Senate and Electoral College over-represent rural districts and voters, many of whom are white. The Republican Party has increasingly restricted the right to vote, particularly where voters of color make a large proportion of the electorate, while mobilizing white, rural voters on the basis of race, even as the share of white, rural voters has declined in the national electorate. After the 2012 election, the Republican National Committee acknowledged this demographic problem in the Growth and Opportunity Project report, calling for an expansion of the Party’s electoral base.

The Party has instead leveraged Senate and Electoral College malapportionment to win the Senate and White House without winning national popular electoral majorities. Republicans have won the national popular vote in presidential elections only once since 1988. In 2016 and 2018, Republicans lost the national popular vote in Senate elections but won chamber majorities. Senate Republican have concurrently used “hardball” procedural tactics to entrench institutional power, particularly in the judiciary. In 2016, Senate Republicans blocked Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, claiming nominees should not be confirmed on the eve of a presidential election. After Republicans won the 2016 presidential election, they appointed Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Comey Barret by narrow margins, with the latter confirmed only days before the 2020 presidential election.

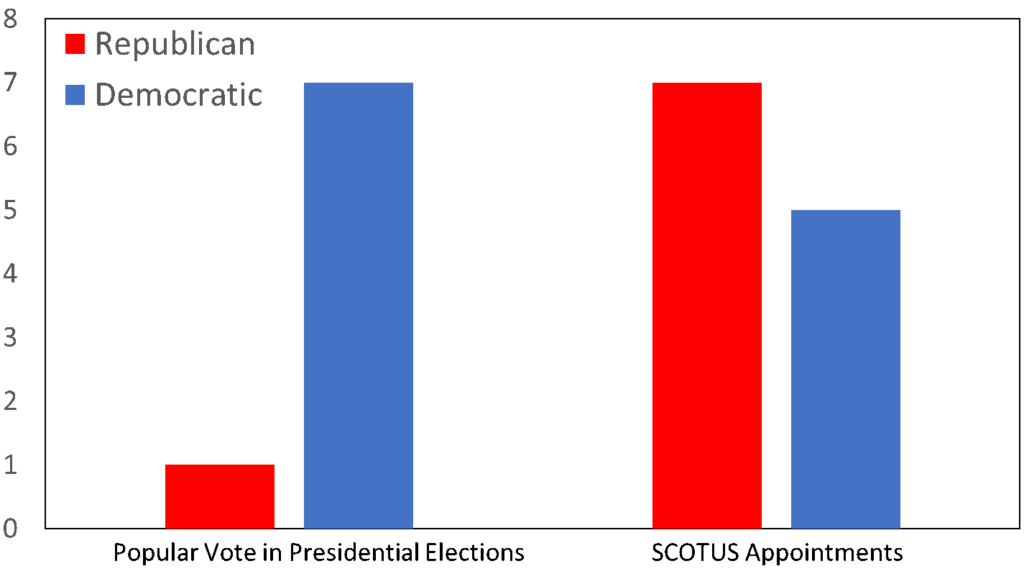

This has shifted the makeup of the federal courts. Since 1990, Republicans have won the presidential popular vote once but claimed seven of twelve Supreme Court appointments. Five sitting Supreme Court justices and half of Article III federal judges were appointed by a Republican president who lost the national popular vote.

Figure 1: Popular Vote in Presidential Elections v. Supreme Court Appointments, 1990-2022

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Court has departed from national public opinion on the matter of abortion access. A recent national Washington Post-ABC News poll suggests Americans support upholding Roe by a two-to-one margin. Prior national polls have shown the same two-to-one support for Roe, including state-level majority support for Roe in most states. Coinciding with the Court’s posturing against Roe, recent polls suggest public faith in the Court’s impartiality have eroded. The Court’s Dobbs opinion nevertheless overturns Roe. What might this mean for abortion and privacy rights?

Congressional response, though vocal, faces high procedural hurdles. Polarization and narrowing majorities in Congress have kept both Democrats and Republicans from making sweeping federal reforms. While Senator Bernie Sanders called for congressional Democrats to statutorily codify federal abortion rights, passage would likely require filibuster abolition, a long-shot. A Court-packing or jurisdiction-stripping bill would similarly require filibuster abolition. Alternately, Congress might use the exceptions clause to strip federal judicial jurisdiction to hear abortion or privacy cases. But past jurisdiction stripping measures have proven contentious, and have been rejected by the Supreme Court.

In the absence of decisive congressional action, the Dobbs opinion will defer abortion regulation to the states. This will create a patchwork system in which abortion is constitutionally or statutorily protected and available in some states and criminalized and unavailable in others. This seems to be Alito’s intent: “In some States, voters may believe that the abortion right should be more even more extensive than the right that Roe and Casey recognized. Voters in other States may wish to impose tight restrictions based on their belief that abortion destroys an ‘unborn human being.’”

Here Alito is not wrong. Many states are poised to restrict or ban abortion access. Thirteen states have “trigger laws” banning abortion after Roe’s reversal, eighteen have laws banning abortion made after Roe, five have unenforced pre-Roe bans, and three states have pending constitutional amendments to ban or restrict abortion. In total, twenty-four states, mainly in the South and Midwest, ban or restrict abortion access. Laws in sixteen other states protect abortion access. And twenty-two states have state equal rights amendments and ten have privacy clauses, giving litigants constitutional grounds to challenge abortion restrictions and bans. Michigan and Vermont have pending ballot measures to constitutionally protect the right to abortion.

This patchwork presents a normative problem. The right to abortion is a type of privacy right. Privacy is a longstanding right in Anglo-American common law, predating the United States and enshrined the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments of the Bill of Rights. It is also a fundamental right – protection of the right should not depend on where one lives. Yet in counties across the Midwest and South – and especially in the poorer, predominantly Black “Blackbelt” Southern counties – residents will be hundreds of miles from the nearest abortion provider. Many, especially low-income and Black and brown people, cannot easily “vote with their feet” by changing residency. The Dobbs opinion thus threatens to create a healthcare caste system for women who cannot easily access abortion. Federalism is a useful tool for allowing diverse solutions to national issues – so long as those issues do not concern fundamental rights. But the Dobbs opinion, in deferring abortion regulation to the states, allows violation of the longstanding, fundamental right to privacy. Abortion regulation should therefore not be left to the states.

This federal patchwork also creates enforcement problems. Individuals in states restricting abortion might visit another state for a legal abortion. Low-income individuals may need travel support from national organizations. While at least one pending bill criminalizes travel for out-of-state abortion, this sort of bill would violate rights to travel across state lines under the Constitution’s Privileges and Immunities Clause. And such a prohibition would be nearly unenforceable. A recent Food and Drug Administration decision allows access to abortion pills through telehealth appointments and to order an abortion drug, mifepristone, through the federal mail. State laws forbidding these out-of-state telehealth appointments would be similarly difficult to enforce.

As one of the authors has argued in a recent book, these thorny interstate enforcement questions often exacerbate controversy. This has especially been the case with privacy rights issues. Prohibitions on interracial and same-sex intimacy were hard to enforce, given the difficulty of policing the bedroom. And couples excluded from interracial or same-sex marriage in one state often married in another – Mildred and Richard Loving, forbidden from marrying in Virginia, crossed the state border to marry in the District of Columbia. Similarly, access to liquor, though not a privacy right, often occurs in the privacy of the home. In the years before nationwide liquor prohibition, pro-liquor “wet” states shipped alcohol through the federal mail into anti-liquor “dry” states, where dry state officers failed to police drinking in private. Some advocates of a national prohibition amendment therefore chastened and hoped to “go just as far and just as fast as public sentiment would justify,” waiting to build nationwide public support before passing a national prohibition amendment. Instead, radical prohibitionists passed the amendment in the face of national ambivalence about prohibition. The Court’s Dobbs decision, contravening nationwide majorities supporting Roe, may produce similar backlash.

The Court cannot unilaterally legislate national policy in the face of strong public opposition. Alito seems to recognize this, noting “This Court cannot bring about the permanent resolution of a rancorous national controversy simply by dictating a settlement and telling the people to move on.” Yet the draft of Altio’s Dobbs opinion, overturning national protection of privacy and abortion rights, imposes a new regulatory regime on an unwilling polity. Widespread non-compliance and non-enforcement may lay bare the impracticality of the Dobbs opinion.

Shaher Zakaria is an adjunct professor of political science at Howard University. His writings focus on Senate malapportionment, the electoral college, and counter-majoritarian topics found in American politics and the Constitution.

Robinson Woodward-Burns is an assistant professor of political science at Howard University. He writes on American constitutionalism, civil and voting rights, and American political development. His first book, Hidden Laws: How State Constitutions Stabilize American Politics, was published in 2021 by Yale University Press.