On January 7, 2021, the New York Times published the following headlines on the print edition’s front page: “After Pro-Trump Mob Storms Capitol, Congress Confirms Biden’s Win” and “A Mob and the Breach of Democracy: The Violent End of the Trump Era.” In the digital edition, these headlines were supplemented by a video titled “Pro-Trump Mob Swarms Capitol.”

While the provocative language embodied in these headlines points to the gravity of the preceding day’s events, one suggestive of a critical moment in the republic’s history, it also invokes two probing questions: first, what is a mob? And second, is the emergence of the figure of the mob a new phenomenon in the American political landscape? Here, turning attention to Hannah Arendt’s understanding of “the mob” offers valuable insight into our contemporary moment and helps shine a light on how the term was frequently used in the nascent republic. Let us tackle the first question first: what is a mob?

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt draws a subtle yet significant distinction between a mob and the masses. Specifically, Arendt asserts that a mob is a group comprised of the “residue of all classes,” thus making it easy to misclassify as a form of the people. The analytic clarity offered by Arendt separates the two categories, placing the mob as a group desirous of a singular leader to rectify their alleged grievances. In contrast, the people engage in political action to implement successful political representation. At its core, a mob is motivated by hatred and hypocrisy, contempt for the society it feels decisively excluded from, and hypocrisy resulting from its dominant mores and values. In this way, mob action strives not to reinstitute a new form of politics, one that is more inclusive or representative, but rather to destroy, qua terror and resentment, the governing institutions of society. Arendt’s definitional treatment of a mob introduces important considerations into the animating principles of mob action. It also, quite decisively, underscores the necessity not to conflate specific socio-political terms, which are frequently used interchangeably, including “mob,” “people,” “masses,” and the “crowd.”

Historically the label of the mob has been almost intrinsically tied-up with attempts to initiate or even reconstitute revolutionary action. This can be seen in the symbols, paraphrenia, and groups, such as the III%ers and Oath Keepers, present at the January 6 Capitol insurrection, who saw their efforts to thwart certification of the results of the Electoral College as a return to the spirit of 1776. Media coverage of the attack certainly did not frame participators as “revolutionaries” or, in a broader sense, as a “failed revolution.” Instead, what is initiated on one side as revolutionary engagement is understood in diametrically opposite terms: mob rule.

This enables us to approach our second question: is the usage of “the mob” a new phenomenon in American politics?

The short answer is, of course, “no.” Contextualizing political action along the lines of mob rule is a common discursive practice in the American republic. But if we look at the issue more precisely, one that seeks to delegitimize political activity, two distinct poles emerge. On the one hand, actions from the alt-Right or far-Right are seen through the framework of mob rule or ochlocracy. In contrast, Leftist praxis, such as BLM or Antifa, are condemned as provocations of anarchy, as Martin Breaugh and I have argued elsewhere. These two poles – mob rule and anarchy – encode discursive practices that engender both an explicit delegitimation of the specific act of political resistance and an implicit critique of the theoretical contours of the animating political projects.

Typically, only one pole of the delegitimation spectrum is grafted upon a political event. For example, as Jason Frank and Noah Eber-Schmid have wonderfully detailed, discourse centered on mob rule was frequently applied to political resistance undertaken by the American colonists, from the Sons of Liberty to the Boston Tea Party and beyond. Thus, the republic’s history reveals a prevalence of how intended revolutionary action triggered counterrevolutionary, reactionary reductionist rhetoric that calls attention to the specter of the mob.

Importantly, if we assess discursive practices post-revolution, we can identify a crucial event characterized by both poles of delegitimation – anarchy and mob rule. As Francis Dupuis-Déri has noted, anti-democratic discourse in the early republic, centered on the interchangeability of the figure of the mob and the threat of anarchy, was used to discredit actors of political resistance as “both irresponsible and dangerous.” And it is here, in the events collectively known as Shays’ Rebellion, that the two poles seamlessly merge.

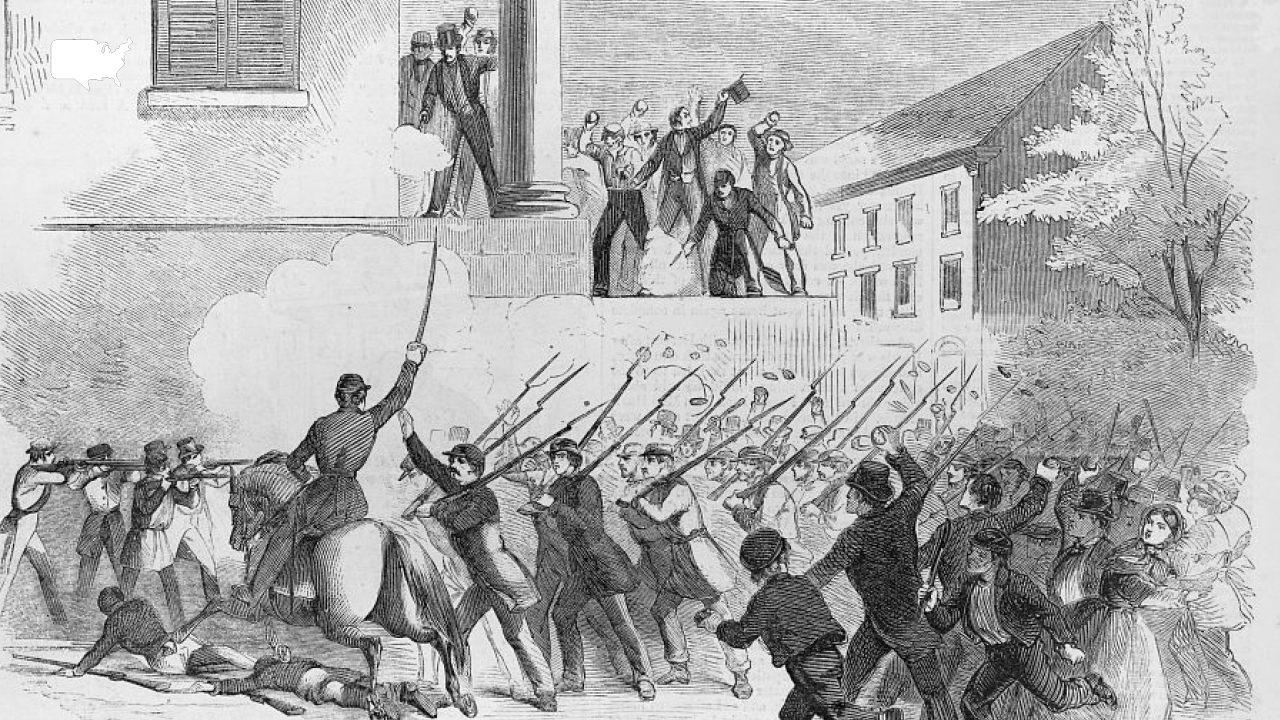

Shays’ Rebellion was a series of ongoing, fleeting, and eruptive moments of resistance targeted directly against the politico-legal institutions of the Massachusetts state. From 1780 to 1786, thousands of farmers across Massachusetts struggled with high levels of taxation, resulting in severe debt-holdings, further aggregated by the possibility of dispossession of land and the confines of a debtors-prison. Farmers directly appealed to the state during this period, petitioning for tax and debt relief; however, their efforts were futile. As the petitions failed to gain any traction in Boston, nearly four thousand farmers banded together to create local committees bent on strategizing a path forward.

Within these democratic committees – erected apart and against the state – farmers burdened with excessive debt and facing an existential threat opened new spaces for action. From August 1786 until the end of February 1787, these farmers would rise, occupying the central public space of towns across the commonwealth, resulting in the closure of courthouses and tax offices. Standing there before the material incarnation of the legal state, the farmers announced and demanded their causes and, in turn, sent shockwaves throughout the aristocratic network of America.

The actions by the dissenting farmers were met with near-universal condemnation on the part of national political leaders. As Terry Bouton argues, the activities of the farmers incited an impulse within the national elites to create a set of “barriers against democracy.” This was seen as necessary to prevent the blooming fervor of uncivilized, backwoods radicalism premating throughout the 1780s and emerging in Massachusetts from infecting the republican body politic

In turn, Shays’ Rebellion became constructed by the political Few as a warning shot: a political and economic threat injected across the national stage that threatened the republic’s foundation. Casting the farmers off as hostiles – and at times, flat-out vilifying them – the inflammatory rhetoric helped shape a national narrative that demanded a new political instrument that could more efficiently respond to domestic turmoil than the limited powers afforded to the national government under the Articles of Confederation.

George Washington was key to constructing this emerging story that spoke to the necessity of force and consolidation of power. Washington saw the “commotions” in Massachusetts as a reflection of mob rule. According to Washington, commotions of this type – those mainly orientated to the disruption of the political and economic vitality of the republic – require immediate extinguishing to thwart the spread of dissent. If not, Washington believed that resistance had a multiplying effect. Coalescing, like a snowball, the “mob” would gather force until an opposition emerged with enough energy to “divide & crumble them.” For Washington, a more robust state was imperative.

Much of Washington’s knowledge of the rebellion came to him through letters from General Henry Knox. Knox’s ominous tone was infused with a graver, more frightening depiction of the farmers, namely a rebellion against reason that directly targeted the wealthy of the state and the very institution of private property. This threat against the sanctity of personal property, according to Knox, threatened the very social fabric of America, a threat so disturbing that a new image, a new understanding of the farmers, needed to be unleashed into the hearts and minds of the national elites to authorize a brutal crushing of the farmers.

To erect such a devastating picture of dissent, it needed to be fashioned in two ways: one, the toilers of the earth were now reduced to a subhuman level, overwhelmed with “turbulent passions” in an animalistic manner, devoid of reason and civility; and second, the actions of these wild animals against reason, and the state, and private property, and wealth, were fashioned together as the very type of association that would undermine the entire architecture of not only the republic, but of Enlightenment ideals writ large. The grave fear was that the republic could crumble, dissolving into anarchy.

The possibility of the agrarian resistance devolving into anarchy struck a resounding chord and intensified fears throughout the elites of the republic. Charles Pettit alerted Benjamin Franklin to the genuine possibility that anarchy would triumph in Massachusetts and throughout the “Eastern States” if not adequately contained. Henry Lee informed Washington that the nation was at a critical junction due to the events of Shays’ Rebellion. For Lee, a federal government must be recreated to deal with destructive, violent events like those taking root in Massachusetts. If not, Lee believed that the people of the United States would be left with no choice but to submit to the brutal “horrors of anarchy and licentiousness.”

In a private letter to James Madison, Washington stressed that the insurrection aimed at a total reconstitution of the American body politic by abolishing debt and wiping away personal property. In Washington’s mind, the nation’s very future was in a state of precarity, as he wrote: “We are fast verging to anarchy & confusion!”

Madison shared in Washington’s critical stance, deeming the rebellion an exercise in treasonous activity and even going as far as to suggest that the effects of the insurrection produced a rebellious substance that was now infused within the body politic of the republic. The impact of this infusion of resistance could not be inoculated. The diagnosis was potentially terminal. Alexander Hamilton, too, was equally inflammatory in his judgment of the rebellion, referring to it as “evil” in Federalist No. 6, which necessitated the use of force as the only effective measure for curing the maladies of the body politic.

News surrounding the events of Shays’ Rebellion reached Thomas Jefferson in late 1786. In a letter written in October of that year, John Jay framed the situation in a hazardous and alarming light that suggested that the American republic would descend into tyranny or, through a reactionary impulse, the “People” would clamor for the return of the image of the One, in the form of the monarch.

In late December, after receiving news from both Jay and John Adams on the events in Massachusetts, Jefferson wrote to Abigail Adams on the matter, hinting at the upshot of the rebellious events in Massachusetts, noting: “I like to see the people awake and alert.”

But Abigail was unconvinced, dismissing Jefferson’s characterization of a “laudible [sic] Spirit” exhibited by the dissenting farmers, instead referring to them as “Mobish insurgents.” “Ignorant, wrestless desperadoes, without conscience or principals,” Adams declared on the nature of the insurgents, further suggesting that they have “led a deluded multitude to follow their standard.” For Adams, the “mad cry of the Mob” threatened the very existence of the republic. In her initial draft of the letter, Adams wrote “the cry of the people.” However, the final letter sent to Jefferson demonstrates an essential shift in her thinking, opting to situate the insurrection in a more radical and condemning light through the actions of a mob.

But Jefferson was unmoved by Abigail’s inflammatory rhetoric and Jay’s account and the reporting of the events as depicted in New England newspapers.

In a letter written to James Madison in January 1787, as the events began to boil to their climax back in Massachusetts, Jefferson emphasized the necessity of rebellion, arguing, “I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.”

In a letter to Abigail Adams in February of 1787, Jefferson once again stressed the “necessity” for rebellion, which he alluded to in his January letter to Madison, albeit this time, in direct relation to the actions of the dissenting farmers in Massachusetts. He writes, “The spirit of resistance to government is so valuable on certain occasions that I wish it to be always kept alive. It will often be exercised when wrong, but better so than not to be exercised at all.”

Our brief voyage through the reactions of prominent national elites during Shays’ Rebellion warrants further examination. Were the events undertaken by the Massachusetts farmers a reflection of mob rule? Or rather, an attempt to enact anarchy? Or perhaps an effort to resurrect and complete the ideals and values of the American Revolution?

What we gain from such an inquiry is an invitation to rethink how specific political terms and categories are deployed in our collective attempts to explain a nation’s past and to better understand and engage in present-day politics. But, perhaps the most critical takeaway is to reappraise Jefferson’s call for a persistent “spirit of resistance to government” and ask: what does that look like in 21st America?

Dean Caivano is a Professor of Political Science and History at Merced College. He was a previous Fellow at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello, VA, and a Visiting Scholar at Centennial Center for Political Science and Public Affairs in Washington, DC. His research focuses on radical and critical democracy, early American political thought, and emancipatory politics. His work can be found in Philosophy & Social Criticism, New Political Science, and Journal of Narrative Politics. He is the author of The Sublime of the Political and A Politics of All: Thomas Jefferson and Radical Democracy (forthcoming).