“Ideological diversity” is a controversial term. Much like free speech, it has been weaponized in our fractious political culture – and injected into our ongoing culture wars. Also referred to as “viewpoint diversity,” the concept has been deployed as a cudgel against political foes to depict them as obsessed with a version of diversity based solely on identity categories such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and (dis)ability status. This is unfortunate, primarily because we risk losing a potentially generative concept in the midst of the scrum on the field. A central tenant of my scholarly work has been the argument that identity, especially racial identity, does not mechanistically determine ideology and that assumptions to the contrary restrict our ability to grasp the full sweep of American intellectual history. This has been particularly salient when it comes to the study of African American conservativism.

In some quarters “black” and “conservative” are still regarded as inherently contradictory, despite several important books and articles that place black conservatism (and black Republicanism) within meaningful historical and sociological contexts. In my own attempt to add to this growing body of literature, I have sought to bring this sensibility into the study of the post-World War II civil rights movement. Civil rights historians have called for a “long” perspective on movement as part of the African-American freedom struggle. I make a case for a “wide” angle, one that highlights the extraordinary ideological diversity within black political culture, both inside and well beyond the movement.

In my current book project, A Different Shade of Freedom, I incorporate center-right perspectives into debates about the nature of African-American citizenship, as well as appropriate strategies for civil rights activism. I do so as part of a larger argument that a diversity of ideological positions ought to be reflected in how we write the history of the movement. If a long history is trans-generational, then a wide one allows for the interplay of competing and colluding visions of the future. If done well, such an approach would open up just enough space for us to incorporate a range of individuals, organization, and ideas associated with what might be called “civil rights conservatism,” and would thereby allow us to trace the influence of various forms of black conservatism on the movement. Why bother? Because it is one thing to proclaim that African American political culture is not monolithic; it is quite another to demonstrate the reality of this proposition in concrete historical terms.

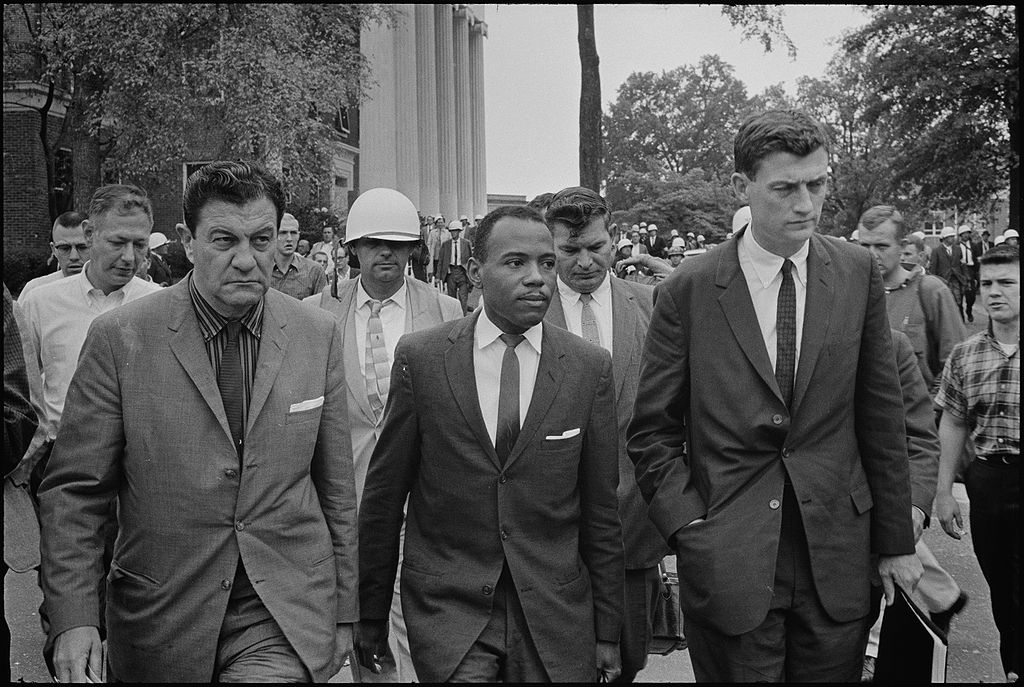

In piecing together this wide history, I explore the political lives and ideologies of a number of figures who sat at a right angle to the movement. There are four in particular. The first is James Meredith, who made history in 1962 when he became the first African American student to officially register at the University of Mississippi. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, this icon of the movement began his long journey toward the New Right, landing eventually on the staff of North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms, and campaigning in 1992 for David Duke during the ex-Klansman’s gubernatorial campaign in Louisiana. In those latter decades, Meredith went on record denouncing integration as a “con job” and standing against liberal social policies such as affirmative action, so-called “forced” busing and welfare rights.

The distance between where Meredith began as a civil rights hero in the early 1960s and where he arrives in the 1990s feels immense. But Meredith belonged to none of the organizations that structured the civil rights movement and was often critical of it in the earlier period as well. I suggest that what he was doing in 1962 was fundamentally misunderstood precisely because the right conceptual and descriptive language had yet to be developed. In the early 1960s, to conceive of Meredith or his activism as “conservative,” given that mainstream conservatives were still waging a war against desegregation, would have been nearly unthinkable. Even today we grope after the proper ideological context for understanding his aims and actions – actions which, I argue, might be seen as pitting a selective desegregation (for talented and exceptional individuals) against integration (for the majority of African-Americans), or what conservatives would eventually come to understand as equality of opportunity versus equality of results.

If Meredith represents the iconic (and often iconoclastic) critic of the movement, then Roy Innis represents the insider critic as an organizational man. As the national chairman of the Congress of Racial Equality – one of the nation’s oldest civil rights organizations – from 1966 to his death in 2017, Innis could not have been further inside of the movement. Curiously, under Innis’ leadership and influence, CORE evolved toward the right through its engagement with Black Power. In 1968, Innis embraced a swiftly conservatizing Republican Party at war with its more liberal wing, and came out strongly in support of Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon. For Innis, this was about rejecting what he characterized as the paternalistic policies of the welfare state and Great Society initiatives advanced by the Democratic Party. Better options for black advancement, Innis asserted, lay in Nixon’s advocacy of community-based schools and policing as well as Nixon’s endorsement of black capitalism.

We tend to think of Black Power as inherently leftist, but much like black nationalism in general, it can have a decidedly conservative inflection not too far removed from the self-help philosophy advocated by Booker T. Washington. By the 1980s, CORE was a full-fledged right-wing organization. What was left of its national and local membership was solidly aligned with the contingent of black conservatives cultivated by networks in and around the Reagan Administration. Those networks, ironically, would begin to systematically undue many of the movement’s gains and objectives under the banner of the need for “new alternatives” in the struggle for African American advancement.

The contingent of new black conservatives also included Dr. Mildred Jefferson. In the taxonomy of civil rights conservatism that I have been developing, she represents the entrepreneur, able to take the trappings of the movement in new directions. Although she did not have deep roots in the civil rights movement, Jefferson was the first African American woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School in 1951 and in the early 1970s she joined the Boston-based Value of Life Committee and helped to found the National Right to Life Committee. She went on to become one of the most vocal pro-life, anti-abortion activists in the nation, always borrowing heavily from the civic and religious ideologies that undergird the black freedom struggle. One frequently hears the civil rights movement praised for its ability to inspire others to press for rights and inclusion, from second wave feminism to gay liberation to the rights of the disabled. One rarely witnesses similar generative connections made with the prolife movement, which for many is an ideological bridge too far. Jefferson blazed and laid the foundations for the collusion between civil rights ideology, the anti-abortion movement and the New Right in ways that continue to reverberate today.

Not only could she demonstrate that the movement was not entirely white, suburban and Catholic, but she also framed abortion as a form of “genocide” (her words) against minorities and the poor, on the one hand, and linked the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v Wade to the 1857 decision in Dred Scott, on the other. Equally important, she is widely credited with making a number of significant connections during NRLC’s early years with individuals and organizations across the conservative network. While she devoted most of her time and energy towards abolishing abortion, Jefferson also took aim against the National Organization of Women and Planned Parenthood for their contributions to the rise of secular humanism, was a critic of both welfare and affirmative action, and an advocate of tough-on-crime measures.

And finally, there is J. H. Jackson, one of the most significant black religious figures of whom you’ve probably never heard. A political moderate – and representative of the power-broker as civil rights conservative – he was willing to stand in active opposition to more militant segments of the civil rights movement while working inside of oppressive systems to negotiate better treatment and conditions for African-Americans through white patronage. History has not been kind to Jackson, but in the 1950s and 1960s he was a towering figure. Head of the National Baptist Convention (NBC) for over four decades, and pastor of Chicago’s historic Olivet Baptist Church from 1941 to his death in 1990, he was a fierce critic of direct action, politically, and of Martin Luther King, religiously, ideologically and personally. He denounced the younger minister as a powder-keg philosopher, and did all he could to blunt his agenda. With some five million members in the 1950s and 1960s, the NBC was the largest national organization of Black Baptists and one of the largest among African Americans in general. It was also a network that amplified the power and authority of its president.

As a moderate during the early phases of the civil rights movement Jackson’s political views were not regarded as unusual. He had supported the legal activism of the NAACP as well as the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Jackson was directly involved in the “Urge Congress” letter-writing campaign to exert pressure on the legislature to enact the 1957 Civil Rights Bill – the first serious piece of federal civil rights legislation since the fall of Reconstruction. It was not until activists adopted more militant direct-action tactics, particularly after the 1960 student-led sit-ins, that he was brought into conflict with the movement and with King.

Jackson found acts of civil disobedience to be profoundly disturbing, both politically and morally. It was also in his view distinctly un-American, and possibly Communistic to boot. Jackson found anything that even hinted at communistic tendencies to be strictly incompatible with civil rights, the word of God, and the dream of African-American incorporation into the American mainstream. This was far from a marginal position, however. Jackson’s anti-Communism was wildly shared by activists such as labor leader A. Philip Randolph and the NAACP’s executive director Roy Wilkins. It was also well in line with positions advocated by the leading black conservative thinkers of Jackson’s generation, especially Zora Neale Hurston and George Schuyler. Jackson, Hurston, and Schuyler each crafted pro-American, anti-Communist positions that stressed individual and collective self-reliance, cast aspersions on the power of the federal government, and attempted to move, in Jackson’s words, away from “politics” toward “production.” In Jackson’s powerful oratory, all of these ideas were strung together in ways that critiqued the more militant wing of the movement and pressed for a more “conservative” self-help alternative.

As he put it in his seminal 1964 address to the National Baptist Convention, the civil rights struggle must be framed not as “a struggle to negate the high and lofty philosophy of American freedom,” nor as “an attempt to convert the nation into an armed camp or to substitute panic and anarchy in the place of law and order.” It is, instead, the very fulfillment of the promise of American freedom and must therefore remain in what he calls the “mainstream” of American democracy. It was imperative, therefore, to “stick to law and order,” and to a “commitment to the highest laws of our land and in obedience to the American philosophy and way of life.” Jackson used this argument and the influence of the NBC to oppose the 1963 March on Washington and most dramatically the 1966 the Chicago Freedom Movement. In subsequently years the Reverend Jackson, too, would find himself increasingly allied with the conservative wing of the GOP.

Jackson, Jefferson, Innis and Meredith are four major figures in the tradition I’m attempting to define as I have sought ways to write them back into the history of the civil rights movement. They each have trajectories that straddle civil rights and conservatism, affording us with opportunities to think about the entanglements between the two most influential social movements of the second half of the 20th century. Each figure has contributed to what I argue is a black conservative archive, often hiding in plain sight, obscured by our own ideological assumptions. A wide civil rights history would have ample room for these African American critics of the movement and the constitutive role they played in shaping civil rights discourse within black communities and in American political culture in general. A wide history would not freeze figures such as Meredith and organizations like CORE in static narratives of activism in the 1960s without reference to their subsequent political evolutions. A wide history would restore figures like J.H. Jackson and Mildred Jefferson. A wide history would not view black conservatism as an ideological orphan, and would not flinch at the prospect that black conservatism is a product of important strategic and philosophical debates within black political culture, especially during the mid-20th century struggle for civil rights and Black Power. A wide history would acknowledge that part of the ironic success of the civil rights movement was that it created space for engagement with an evolving conservatism in the 1970s and 1980s while exerting both direct and indirect influence on the course of that evolution.

Angela D. Dillard is the Richard A. Meisler Collegiate Professor of Afroamerican and African Studies and in the Residential College at the University of Michigan. Specializing in the study of political ideology in the context of social movements, she is the author of Faith in the City: Preaching Radical Social Change in Detroit (U of Michigan Press, 2007); and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Now?: Multicultural Conservatism in America (NYU Press, 2001): among the first studies of political conservatism among African Americans, Latinos, women and homosexuals. She is currently at work on a book, A Different Shade of Freedom, about intersections between the civil rights movement and the rise of a New Right.