Stephen Girard, merchant, banker, and the richest man in America at the time, died in 1831. Mr. Girard left the vast majority of his fortune to the City of Philadelphia—approximately six million dollars. In Girard’s final action, his will, he tried to say that good citizenship in a republic could be produced without religion. Girard did this by earmarking two million dollars for the creation of an orphanage for poor, white, orphan males and stipulating that clergy could never enter that campus. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story commented on the effect of the gift in a February 7, 1844 letter, “The curious part of the case is, that the whole discussion has assumed a semi-theological character . . . Mr. Jones and Mr. Webster, contended that these restrictions were anti-Christian and illegal.” Thus, the major issue of the case was whether the will was hostile to Christianity, which would have made it hostile to the common law of Pennsylvania. Was the Devil trying to remove the foundation of all law, education, and society through this bequest?

Critical to understanding Girard’s will is grasping how large the gift was. A 2014 CNN article estimated that in contemporary terms the estate would be worth $120 billion dollars and listed Girard as the fourth richest person in American history. Girard had lived a life dedicated to philanthropy and was greatly admired for his leadership during the Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793, for being the largest financer of the United States in the War of 1812, and for his financial support of the Second National Bank. The most often attributed quotation of Girard illustrates his dedication to civic action, “My deeds must be my life. When I am dead my actions must speak for me.”

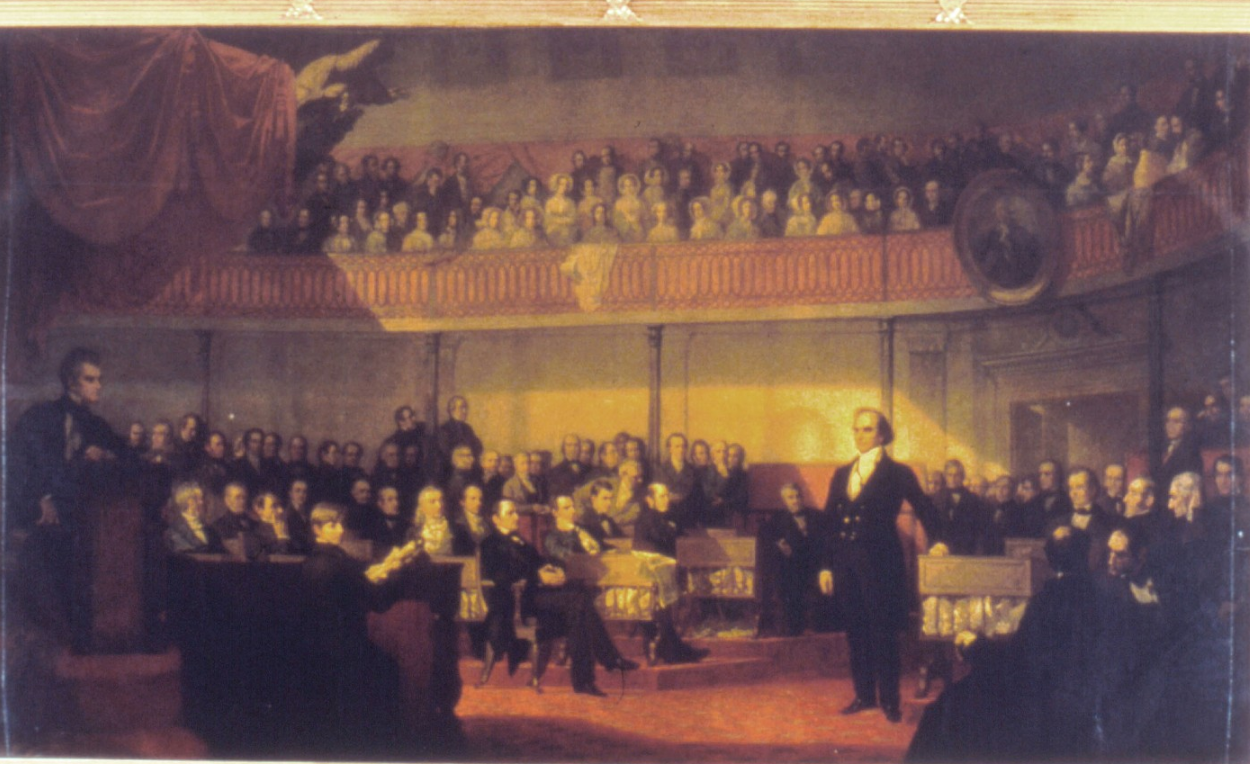

The will was opposed by Girard’s relatives who, wanting the fortune for themselves, hired the former and future Senator, Daniel Webster, the best attorney in the country and recent US Secretary of State. Webster argued that the will was hostile to Christianity and thus hostile to the notion that Christianity was a part of Pennsylvania’s common law, and that education without religion was of no use to society at all. Webster lost, but it is not clear that the will was truly understood by the Court the way Girard wanted it to be. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, in the case of Vidal v. Girard’s Estate (1844), acknowledged the maxim that Christianity was a part of the common law but that it must be understood in light of the new American (and Pennsylvanian) protection of liberty of conscience. The challenging of Girard’s will illustrated a contest in America between those that maintained government must promote religion and those who favored a strict separation of Church and State. The resolution of the case helped to establish an understanding that while government could promote religion, it could not prevent dissent.

Girard, after stating in the will how he had long believed in the development of the moral principles and education of the poor, stated his vision: “I am particularly desirous to provide for such a number of poor male white orphan children, as can be trained in one institution, a better education, as well as a more comfortable maintenance than they usually receive from the application of the public funds.” The vital fight over civil rights issues involving the City of Philadelphia administering a boarding school for white male orphans was still to come. The controversial issue in the 1844 case centered on section twenty one of the will,

Secondly, I enjoin and require that no ecclesiastic, missionary, or minister of any sect whatsoever, shall hold or exercise any station or duty whatever in the said college; nor shall any such person ever be admitted for any purpose, or as a visitor, within the premises appropriated to the purposes of the said college. [sic]

To the shock of the public, Mr. Girard forbid all clergy from ever stepping foot on the campus of his school.

While he occasionally described himself as Catholic, Girard named his ships after French enlightenment philosophers including Voltaire, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Helvetius. He was also known as a dedicated Mason — an organization that promoted civic benevolence disconnected from any particular religious belief. Following the prohibition of clergy on campus in the text, Girard explained why he wanted this, “In making this restriction, I do not mean to cast any reflection upon any sect or person whatsoever; but, as there is such a multitude of sects, and such a diversity of opinion among them, I desire to keep the tender minds of the orphans, who are to derive advantages from this bequest, free from the excitement which clashing doctrines and sectarian controversy are so apt to produce.” For Girard, the possibility of obtaining knowledge of the Divine was bleak. Perhaps he thought this of all metaphysical questions, insisting in the will that students be “taught facts and things, rather than words or signs.”

Religion tended to lead to more strife than harmony and it was better for orphans to focus on the practical skills required for the marketplace, like navigation, surveying, and French and Spanish than quarrel about doctrines of faith. After being taught “the purest principles of morality” and love of “truth, sobriety, and industry” their mature reason could choose a religion they preferred as adults. Still, Girard believed in education for citizenship as critical for his orphans. The teaching of “the purest principles of morality” were supposed to produce a habit of “benevolence towards their fellow creatures” but more than that, the education was supposed to produce the virtues of toleration and patriotism. Girard stated, “And, especially, I desire, that by every proper means a pure attachment to our republican institutions, and to the sacred rights of conscience, as guaranteed by our happy constitutions, shall be formed and fostered in the minds of scholars.” Girard envisioned the graduates of his orphanage being prepared to contribute to society through industry, introducing religion into the curriculum could distract from that and as such he banned clergy from entering the campus.

It was on this issue that Daniel Webster argued that the bequest could not go forward. Webster stated that in creating this charity, Girard had burdened the citizens of Philadelphia with a school that violated the public policy of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Since “poor white male orphan” was not specific, the will was only sustainable as a charity. But charities must be useful to society. Webster’s argument echoed what George Washington said in his Farewell Address about the need of republican government to have the self-restraint that comes from religion, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Webster argued that the will should not be enacted because it was hostile to Christianity and Christianity was a part of the common law of Pennsylvania. According to Webster, religion was the unifying principle of education; the orphans would not really be educated without it. The will, therefore, violated the customs of Pennsylvania.

The City of Philadelphia hired Nicholas Biddle, an important banker, lawyer, and past friend of Mr. Girard, to defend the will. Biddle argued from the text of the will, rather than the spirit of the will. Nothing in the text explicitly forbid the teaching of Christianity, it simply forbid ministers. As such there could not possibly be anything that violated the doctrine that Christianity was part of the common law. Webster argued that this interpretation made little sense. By excluding clergy, it stigmatized the clergy. Especially since it allowed for followers of any other doctrine to enter campus. The students could be taught from a disciple of Voltaire but not a Christian minister. Webster maintained that all Christian sects had some form of ministers since the time of the apostles. The clergy was a central element of Christianity as was educating the young in the faith. Biddle’s claim that teachers who were not ministers could still teach Christianity made little sense because the object was to prevent strife. How would having less credentialed instructors prevent the strife over doctrines that Girard intended? Webster maintained that to accept the will required the Court to do what Mr. Girard wanted—create a school free from religion.

For Webster, Christianity was central to education and the Girard orphans would spend at least a third of their lives (until the age of 18) without it. At a certain point, every person will ask fundamental questions about human existence such as, “shall I live forever?” and “if a man die, shall he live again?” Christianity answers these questions; it orders student’s lives by telling them the meaning of life in service to others and telling them about rewards and punishments in the next life. These orphans would not get the meaning of life as part of their education. They would also not be prepared for the religious society that they lived in. There is a diversity of religious sects in the world and school is the place where one learns to accommodate themselves to each other. As Webster described it the graduates of Girard’s orphanage raised on a secular education would not even be prepared to understand what it would mean to take an oath in a court of law.

Lastly, Webster argued that because the will was hostile to Christianity, it was hostile to the common law of Pennsylvania and the customary way of life of the citizens of Philadelphia. While the doctrine that Christianity was part of the common law was often cited, it rarely had much impact in cases. It meant that there was a crime of blasphemy but that crime had more to do with disturbing the peace than the truth of the religion. It was often cited as the basis for Sunday laws that mandated businesses close, but those were also justified on the need for a day of rest. It did mean that testimony given after swearing on the Bible was given more weight and that contracts that violated Christian morals were often unenforceable, but those types of contracts usually violated the criminal law as well. Primarily it meant there was a background of higher law from God that the decisions in cases were trying to articulate and that the people of England and America who had the common law were Christians.

Realizing, that the crime of blasphemy required outright hostility to Christianity and not simply dissent, Webster tried to argue that Girard’s will violated the customary life of the citizens of Pennsylvania and forced them to participate through creating and maintaining this orphanage. Webster fought for the custom of a people as a basis of law in much the same way Thomas Aquinas argued it should be in the Summa Theologica (ST I-II Q97a3). There Thomas argues that for free citizens, consent of the whole people is what really counts as the basis of law and that this can be indicated through custom. Webster says, “It is the same in Pennsylvania as elsewhere, the general principles and public policy are sometimes established by constitutional provisions, sometimes established by general consent…Everything declares it. The massive Cathedral of the Catholic, the Episcopalian church… the plain temple of the Quaker…The dead prove it as the living…We feel it. All, all proclaim that Christianity…general, tolerant Christianity is the law of the land.” Webster argued that Girard’s will violated the unwritten customary law of Pennsylvania in asking Philadelphia to administer a school that eliminates a key aspect of Pennsylvanian life, Christianity. This argument was enormously popular among religious people across the country, though it may have added fuel to the fire of rumors that immigrant Catholics were attempting to get the King James Bible taken out of public schools. Philadelphia would erupt in Bible riots on this issue that same year. Webster turned the text of his argument against the will into a campaign pamphlet for his 1844 Presidential run. In sum, Webster argued the Girard will was no charity at all. It was education without the knowledge that makes education worthwhile, hostile to Christianity, and as such against the common law and way of life of the people of Pennsylvania.

The most famous defender of the doctrine that Christianity was the basis of the common law wrote the majority opinion in the Vidal v. Girard’s Executor case, Justice Joseph Story. Also, Harvard University’s Dane Professor of Law, Story had answered Thomas Jefferson’s denial of the maxim in the American Jurist and Law magazine saying, “can any man seriously doubt, that Christianity is recognized as true, as a revelation, by the law of England that is by the common law?” But the notion that Christianity was a part of the common law did not mean there could not be dissent, only outright blasphemy was illegal, especially in an American state that tried to give maximum liberty of conscience like Pennsylvania. The constitution of Pennsylvania stated that “all men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences.” Story insisted that this included eccentric beliefs, like deism and even atheism, in his unanimous decision:

Language more comprehensive for the complete protection of every variety of religious opinion could scarcely be used, and it must have been intended to extend equally to all sects, whether they believed in Christianity or not, and whether they were Jews or infidels. So that we are compelled to admit that although Christianity be a part of the common law of the state, yet it is so in this qualified sense, that its divine origin and truth are admitted, and therefore it is not to be maliciously and openly reviled and blasphemed against, to the annoyance of believers or the injury of the public.

Story as a Unitarian was a religious minority and seemed supportive of Mr. Girard’s right to arrange his last will and testament in accord with his religious views. However, Story also followed Nicholas Biddle’s argument that there was no hostility to Christianity in the will, only a ban on ministers. Story stated in his opinion, “remote inferences, or possible results, or speculative tendencies, are not to be drawn or adopted for such purposes. There must be plain, positive, and express provisions, demonstrating not only that Christianity is not to be taught, but that it is to be impugned or repudiated. Now in the present case there is no pretense to say that any such positive or express provisions exist, or are even shadowed forth in the will. The testator does not say that Christianity shall not be taught in the college, but only that no ecclesiastic of any sect shall hold or exercise any station or duty in the college.” The faculty of Girard’s school were still free to teach religion to the pupils, they could still read the Bible, and that nothing in Girard’s phrase “the purest principles of morality” excluded Christianity.

While Daniel Webster lost the case of Vidal v. Girard’s Executor, it was not quite true to say the Devil won. Story said that the will would have been permissible even if it outright banned religion on campus. But since Girard did not explicitly do this, the Court would not infer his opposition to Christianity. The orphanage would be created and it would exclude ministers but it could still be a place where Christianity was taught. Justice Joseph Story basically came to the conclusion that majorities have the right to promote their religion in America if they allow liberty of conscience for dissenters. Thus, Story’s conclusion in this case was not terribly different from what he wrote about the meaning of the 1st Amendment in his Commentaries on the Constitution, “That Christianity ought to receive encouragement from the state, so far as was not incompatible with the private rights of conscience and the freedom of religious worship.” Story understood Church and State in America and in Pennsylvania to be separate institutions that supported each other within bounds. As it says at the start of Isaiah 49:23, “And kings shall be they nursing fathers.” Promotion of Christianity was not understood to be an establishment of religion, but it was not the state’s job to root out heresy and non-belief. America was not a Christian nation but it was on the whole, a nation of Christians. Mr. Girard’s school could proceed as long as it was not openly hostile to the beliefs of that society. In the absence of an explicit forbidding of the teaching of Christianity, Girard’s orphans would receive a normal education, a religious one, but per Girard’s explicit directions, that education would not come from ministers. This position constituted the American consensus on religion and government until the 1960’s when in cases like Engel v. Vitale the Court began insisting on a much sharper separation of church and state.

Rudy Hernandez is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Political Thought & Constitutionalism at the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy at the University of Missouri.