While giving a campaign interview in 2014, Matthew Whitaker, at the time a Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in the state of Iowa, was asked to name the worst Supreme Court decisions in history. Marbury v. Madison (1803) immediately came to Whitaker’s mind. “There are so many (bad rulings),” Whitaker told his interviewer. “I would start with the idea of Marbury v. Madison. That’s probably a good place to start and the way it’s looked at the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of constitutional issues. We’ll move forward from there.”

Since assuming his post as Acting Attorney General of the United States in November 2018, Whitaker’s comments have taken on new resonance. Whitaker chose to pummel Marbury in the 2014 interview with a cudgel familiar to most Marshall Court critics. Having dispensed with Marbury, he went on to slam “all New Deal cases that were expansive of the federal government,” which in his view lead “all the way up to the Affordable Care Act and the individual mandate.” By Whitaker’s account, Marshall’s opinion in Marbury represented the first fateful step toward the rise of America’s judicial Leviathan. Sadly, the Attorney General did not lacquer his criticism with phrases borrowed from the Monster of Malmesbury.

Somewhat surprisingly, Whitaker did not cite Chief Justice John Marshall’s participation in the Marbury case as its biggest problem. The Chief Justice’s involvement continues to be a legitimate criticism of Marbury. Marshall, as then-President John Adams’ Secretary of State in 1801, was tasked with delivering the judicial commissions (notably, to one William Marbury) that were at the crux of the dispute. Marshall did not deliver the commission, and then presided over the case in his new position on the Supreme Court as if he was never involved in the incident at all. Given these facts, one might forgive Jefferson for hating him.

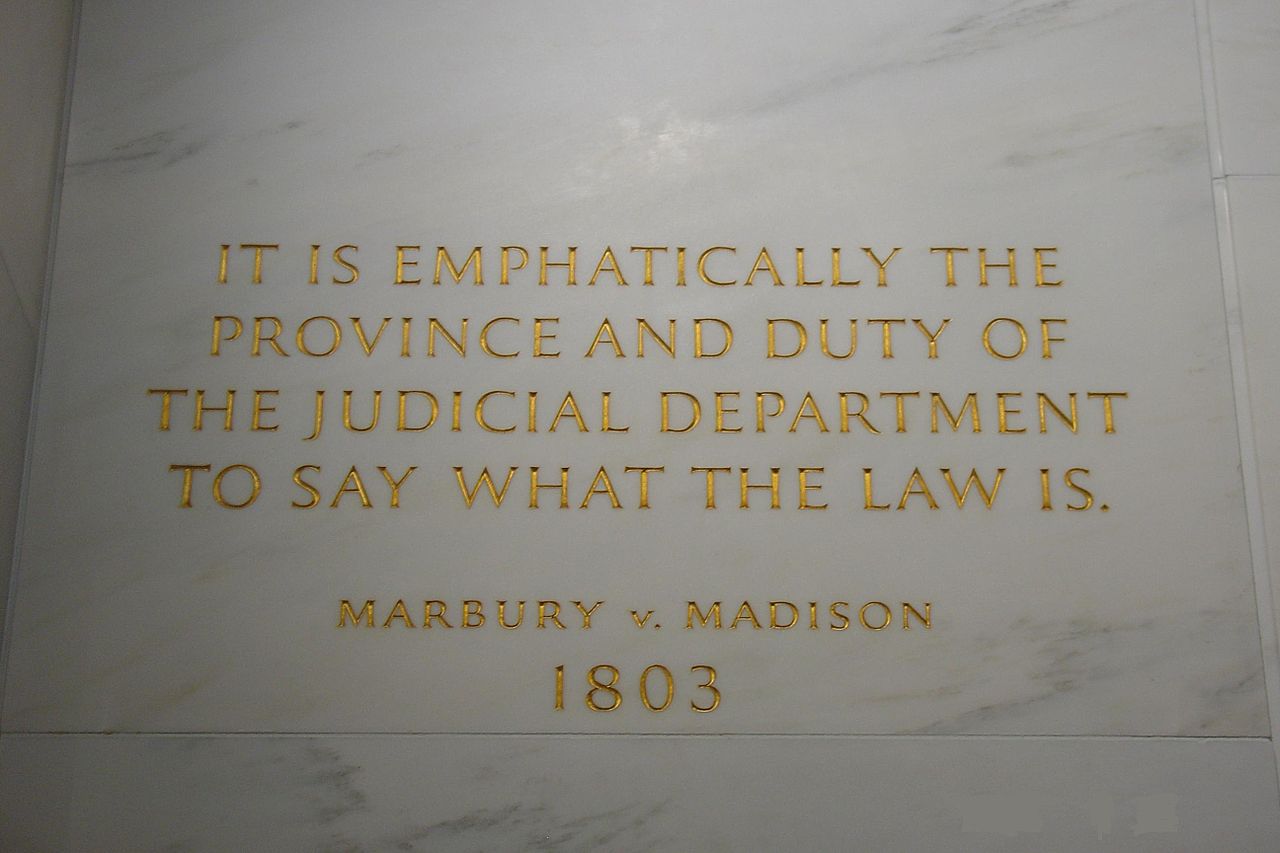

Presumably, Whitaker’s grievance with the case has to do with arguably the most famous line of Marshall’s opinion: “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” Admittedly, this is not the language of restraint. But the principle inherent in the sentence—that the judiciary is responsible for determining, enunciating, and defending the higher law of the Constitution—was hardly unheard of in 1803.

The practice of judicial review dates back to at least the writings of William Blackstone and the common law tradition in England, and was a widespread phenomenon in state courts throughout the colonies and during the republic’s early years. Moreover, the Supreme Court itself had already suggested the power of invalidating congressional acts in the earlier case of Hylton v. United States (1796). That dispute involved the arcane question of whether a tax on the possession of goods constituted a direct tax, in which case it needed to be apportioned among the states.

The Court, in the Hylton case, ended up concluding that the tax was not unconstitutional (“I am clearly of opinion this is not a direct tax in the sense of the Constitution,” James Iredell noted in his opinion), but as is so often the case for such decisions, what the Court didn’t say is perhaps just as important. In upholding the federal tax as constitutional, the Court had assumed a general power to review the constitutionality of any act of Congress. It had not struck down the federal law on this occasion, but suggested that it had the power to render such acts null in the future. It did so seven years later, when Marbury rendered null and void section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the only occasion the Court invalidated an act of Congress during Marshall’s tenure.

Marshall was not so much pioneering as perpetuating a longstanding practice of the judicial power, one that had already been suggested by the Court in Hylton. Seen in this light, Marbury is more traditional than iconoclastic. Indeed, several professors of constitutional law either decline to teach Marshall’s opinion or at least stress its lack of novelty. In contrast to the view of President Trump’s Attorney General, the constitutional law professor Mark Graber has argued that the “popular notion that Marbury established judicial review by judicial fiat is nonsense.”

Even if Marshall did not invent a new practice out of whole cloth, does he nevertheless deserve at least some of the blame for later instances of supposed judicial overreach and activism? Perhaps. It is true that his opinions in such cases as McCulloch v. Maryland and Gibbons v. Ogden provide generous constructions of congressional authority, possibly providing leverage and cover for justices seeking to rob the people of power. There are loaded phrases in such opinions that can be picked out to show that Marshall was the forefather of the impressionistic style of constitutional interpretation that conservatives deride.

But just as there are two sides to every dispute, there are also usually two sides to every interpretation of an opinion. Before we accept Whitaker’s view that Marshall’s logic in Marbury somehow anticipates the modern welfare state, we should remember that the opinion can also be viewed as a relinquishment rather than seizure of illegitimate judicial authority. Marshall famously ruled that the Court could not issue a remedy to William Marbury, the man who took his injury to the Court directly thanks to the widening of the Court’s original jurisdiction granted by the Judiciary Act. Even if Marshall wanted to help him, which he badly did, the Constitution would not allow it. In invalidating the authority bestowed on the Court by Congress, Marshall was essentially saying to elected officials of his time what every good libertarian would surely like to hear more of today: “You’re giving me more power than the Constitution says I should have; take it back, I don’t want it!”

The contested legacy of Marbury captures some of the ongoing debates about the role of the unelected justices in liberal democratic governments. In the course of these arguments, we must be on the guard against Fake News—and Fake History.

Clyde Ray is currently a visiting professor at La Salle University, where he teaches courses in American government. He earned his Ph.D. in political science from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He is author of John Marshall’s Constitutionalism, to be published by the State University of New York Press in summer 2019.