There is a parallel between the American decision to leave the British Empire in 1776 and the British vote to leave the EU in 2016: both movements emphasized their localist credentials through a confrontational narrative that was anti-establishment, anti-corporate and anti-globalist.

On June 23, 2016, the British electorate voted narrowly for “Brexit”: for Britain to leave the European Union (EU). At 4 a.m. Nigel Farage, the leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and a vocal campaigner for Brexit, took to the stage. Greeting his cheering supporters, Farage delivered a short victory speech that denounced the global political and economic establishment. “We’ve fought against the multinationals,” he proclaimed, “we’ve fought against the big merchant banks, we’ve fought against big politics, we’ve fought against lies, corruption and deceit.” Forecasting the collapse of the European Union and the return of national sovereignty, Farage announced that June 23 would be forever remembered as Britain’s “independence day.”

The call was soon echoed by Boris Johnson, the former Mayor of London, and the Lord Chancellor Michael Gove, and before long the comparison was being made across the Atlantic. Soon pundits from across the political spectrum were speculating whether or not the Founding Fathers would have supported Brexit. Were bureaucrats in Brussels as unaccountable to the British electorate as Westminster had been to eighteenth century American colonists? Was the widely publicized and highly controversial figure of £350 million a week raised from taxpayers in Britain and destined for EU coffers a rallying cry to rival colonial demands for “no taxation without representation”? Were British demands for the independent regulation of immigration and trade an echo of the Declaration of Independence signed in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

Unsurprisingly, critics quickly identified numerous historical problems with the comparison. Unlike the colonial Americans excluded from Parliament, Britons are represented in Brussels (Farage himself serves as a Member of the European Parliament) and Britain has ultimately maintained its national sovereignty. And, unlike in the case of the American Revolution, Brexit has not yet triggered a bitter conflict fought across four continents. Nonetheless, there is a parallel between the American decision to leave the British Empire in 1776 and the British vote to leave the EU in 2016: both movements emphasized their localist credentials through a confrontational narrative that was anti-establishment, anti-corporate and anti-globalist. Indeed, the political discourse of anti-globalism that we are familiar with today has a history in British and American political culture that stretches back at least as far as the eighteenth century.

In the mid-eighteenth century there was intense interest in the political consequences of new relationships between individuals in different and distant countries: in “globalization.” This was a time of dramatic expansion in long-distance commerce, communications, and investment. It was also a period of extraordinary expansion in information about events in other countries, and of reflection on the political importance of this information. “The industry of the north is transported to the south; the materials of the east clothe the west, and everywhere men have communicated to each other their opinions, their laws, their habits, their remedies, their illnesses, their virtues and their vices,” the Abbé Raynal wrote in a best-selling economic commentary in 1770. Continents were connected as though by “flying bridges of communication,” that for Raynal constituted a “revolution in commerce, in the power of nations, in the customs, the industry and the government of all peoples.”

THE COMMERCIAL CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BRITAIN AND THE AMERICAN COLONIES WERE NEVER MORE LUCRATIVE THAN THEY WERE IN THE PERIOD IMMEDIATELY PRECEDING THE REVOLUTIONARY CRISIS OF 1774.

British Americans were an important part of this newly connected world. On the eve of independence, Americans were part of the largest economic and political union on earth. As members of the British Empire, they had access to markets in Europe, North America, Africa and Asia on far more favorable terms than their non-imperial competitors. Colonists could easily acquire products from Britain and its extended empire, while benefiting from the commercial opportunities that the empire presented. Colonial merchants, for example, profited considerably from unrestricted access to markets in the British Caribbean where they sold slaves transported from West Africa, rum distilled in New England, and fish harvested from the northern Atlantic. The Navigation Acts, a set of legislation regulating trade, were widely seen as the foundation of British prosperity and power, “the cornerstone of the policy of this country with regard to its colonies,” according to the British politician Edmund Burke in 1774. Although the legislation was designed to support the domestic rather than the colonial economy, the 1760s and early 1770s were a period of remarkable economic expansion in the North American colonies. Measures restricting foreign access to imperial trade, for example, significantly stimulated the New England shipping industry. “Their seas are covered with ships, and their rivers floating with commerce,” one English pamphleteer wrote in 1768. Exports from England and Scotland to the thirteen colonies increased almost 300 percent between 1769 and 1771. The commercial connections between Britain and the American colonies were never more lucrative than they were in the period immediately preceding the revolutionary crisis of 1774.

Americans were not restricted to trade within the British Empire, however, but were increasingly integrated within a global economy where manufactured goods circulated in exchange for colonial resources such as furs, timber, sugar, rice, indigo, and slaves. Imperial restrictions rarely prevented British Americans from trading with the Spanish, French, Dutch, or Portuguese as smuggling became an important mechanism for circulating tea and other foreign imports within and among colonial economies. And Atlantic trade economies grew ever more dependent on links to international credit, services, and goods. Spanish American silver, for instance, made the tea trade possible by providing European merchants with the hard currency necessary to obtain commodities in the East Indies, where the purchasing power of silver was far greater than in Europe. American demand brought these Asian commodities full circle, making tea one of the fastest growing consumer products by the mid-eighteenth century and a crucial component of the British commercial empire.

The rise in demand in the colonies for commodities and goods from around the globe meant that British Americans were increasingly dependent on merchants and bankers in Britain and Europe for credit to invest in their plantations or to purchase goods for resale throughout North America. The politics of global credit became widely discussed as the century progressed. The financial crisis of 1763 “spread Terror to every commercial City on the Continent,” according to one observer. Nine years later, in 1772, a major credit crisis began with the failure of a London bank which caused shockwaves around the world. Banks across Britain were ruined, forcing them to call in debts from Virginia planters, resulting in bankruptcies and suicides across the colony. The crisis spread to Amsterdam, the failure of Dutch banks with speculative holdings in the East India Company, the bankruptcy of the Company’s chairman, and the collapse of the Company’s stock. The Company received a government loan of £1.4 million to avoid bankruptcy, and making the Company profitable became a major priority.

One proposal to improve the Company’s fortunes was a tax cut enabling it to sell its stockpiles of tea competitively in British America. New legislation in 1773 allowed the Company to ship surplus tea to America without paying customs duties in Britain. To reduce the price for American consumers further the tea was to be sold only through designated agents, cutting out the costs of merchant middlemen. This created a large number of powerful losers: the merchants who traded in tea but were not made agents and those who had made profits from selling smuggled tea, which now lost its commercial advantage in the face of cheaper British imports. Opposition to the East India Company’s tea was widespread, but it was in Boston, in December 1773, where a group of tradesmen disguised as American Indians threw large quantities of tea overboard into the harbor.

BRITISH POLITICIANS FAILED TO UNDERSTAND THAT TEA HAD COME TO REPRESENT THE POLITICAL CORRUPTION OF THE NEW GLOBAL EMPIRE, AND THE POWERLESSNESS OF INDIVIDUALS IN DISTANT PROVINCES.

The Boston Tea Party, as it became known, was a symptom of broad concerns regarding the political consequences of global commerce and influence. To politicians in London, however, the American resistance to the tea came as a surprise. Lord North, the prime minister, commented that “it was impossible for him to foretell the Americans would resist at being able to drink their tea at 9d. in the pound cheaper.” Tea had long been a symbol of foreign luxury and extravagance, described as a poisonous weed, or accursed trash, or, for Thomas Jefferson, an “obnoxious commodity,” that was believed to bring dependency, selfishness, and a loss of virtue. British politicians failed to understand that tea had come to represent the political corruption of the new global empire, and the powerlessness of individuals in distant provinces. The tea was said to have been poisoned by the English Ministry, with political and perhaps also with physical corruption. The “herb sent o’er the sea,” or the “outlandish tea” with its “noxious effluvia,” was said, in a popular song published in New Hampshire, to be “tinctured with a filth/of carcases embalmed.”

The tea was evidence, or so it seemed, of the corruption of remote politicians and of their disdain for the individuals who were affected by their policies. British naval and customs officers were chastised as “pimping tide-waiters and colony officers of the customs,” by Benjamin Franklin, or “customs house locusts, catterpillars, flies and lice,” according to one Rhode Island newspaper. The connection of the tea with the empire of global commerce was particularly disturbing. The fact that the tea had come from China, and was the property of the East India Company, was invoked countless times. Philadelphia lawyer John Dickinson compared the oppression of the East India Company in America to being “devoured by Rats.” The watchmen on their rounds, he said, should be instructed to “call out every night, past Twelve o’Clock, beware of the East-India Company.” The Company had corrupted Britain and had wreaked “the most unparalleled Barbarities, Extortions and Monopolies” in Bengal, he wrote, and now they “cast their Eyes on America, as a new Theatre, whereon to exercise their Talents of Rapine, Oppression and Cruelty.” The Boston Tea Party set Britain and its colonies on a collision course. Parliament passed legislation to punish Boston and recoup the value of the lost tea, which prompted unified resistance from the thirteen colonies and ultimately led to independence.

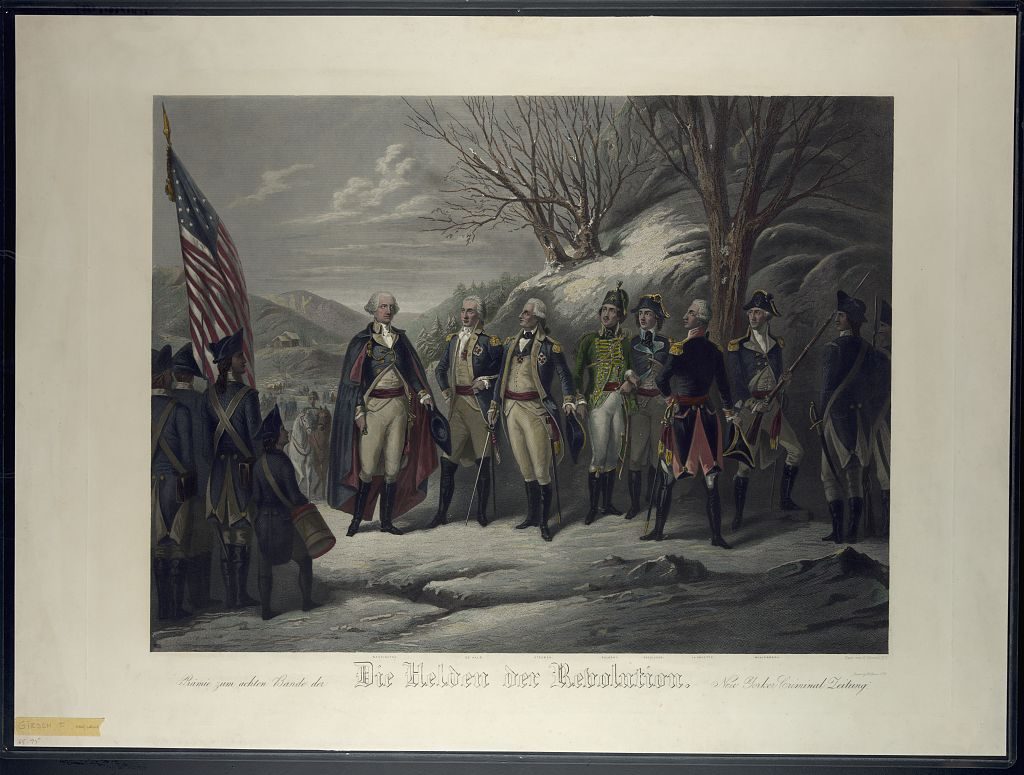

The rejection of the politics of global commerce and credit was a crucial political discourse in the revolutionary movement in the American colonies. The Declaration of Independence explicitly referenced the politics of global commerce among their grievances: the depredations of the British king included “cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World,” and “Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence.” The British Empire was increasingly seen to be corrupted by its association with the East India Company, its commercial interests at odds with the security and prosperity of the American colonies. Similar sentiments have been attributed to Britain’s rejection of the EU in 2016. Voters believed that they did not benefit from the current system, and that the free movement of goods, labor, and capital only benefited a privileged few. They believed that the establishment worked in the interests of corporations, not them. It remains to be seen whether Brexit will offer any solutions to these issues. Nonetheless, by drawing on an anti-globalist discourse with a rich trans-Atlantic history, Farage was perhaps right to liken 2016 to 1776.

Jonathan Chandler is the Fulbright Robertson Visiting Professor of British History at Westminster College, Missouri for 2016-17. His book, War, Patriotism, and Identity in Revolutionary North America is forthcoming with Boydell & Brewer Press.