Henry Clay attempted to render compromise a political virtue. In a time of weak parties, sectional strife, and agitation from abroad, Clay understood that the Speaker of The House needed to appeal to Republicans and Federalists alike if he wished to unify coalitions and pass substantive policy to affirm American independence, facilitate self-government, and urge economic progress.

In an 1830 letter, Henry Clay advised his son that, while he should be civil to all men, “there is no incompatibility between the practice of the greatest urbanity and the most steadfast adherence to our principles.” To Clay, leading compromise was a form of conquest whereby he could win over adversaries and attempt to bind together the sectional wounds of the nation. Through Clay’s leadership in the Missouri Compromise, he would attempt to bridge the gap between the sectional parties that would soon develop and threaten to break up the union.

CLAY’S WORK AS COMPROMISER PROMPTS IMPORTANT QUESTIONS ABOUT THE ROLE OF THE AMERICAN STATESMAN, THE SPIRIT OF THE CONSTITUTION, AND REPRESENTATIVE SELF-GOVERNMENT.

In Clay’s time, as in our own, compromise comes with criticism. How can one be considered a serious statesman if he is willing to forgo his principles to placate political friends and adversaries alike?

What are we to say of the man who departs from principle to grope for resolution in the face of a crisis? Clay’s Constitutional interpretation, and his political legacy, is often questioned in such a manner.

One historian remarked that Clay “moved from broad to narrow to various in between interpretations of [the Constitution] with the ease of changing his vest.” Indeed, Clay saw no inconsistency in, for example, vigorously supporting Missouri’s exclusive jurisdiction over slavery in March of 1820, while weeks later championing a protective tariff that would meddle with the states’ freedom to determine their own trade policies.

Clay saw no inconsistency between economic nationalism and a robust defense of states’ rights because he viewed the two as essential to constitutional unionism. Clay understood what Madison observed in Federalist 39—that the union was “partly federal and partly national.” He understood that union necessitated the exercise of certain federal powers to bind the states together, while also affording the several states freedom to determine certain legislation for which the federal government had no constitutional precedent to determine..

The endeavor to safeguard the union obligated Clay to observe the limits of Congress’ power in certain instances where states would pursue their own interests, while allowing him to pass policies that would bring the endeavors of the several states into consonance under the principles of the Declaration. As for Missouri’s jurisdiction over slavery within its own territory, Clay understood that Congress had yet to affirm the power of the federal government to limit a territory’s decision regarding slave “property” that existed at the time of its application for statehood. Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi had all entered the union as slave states with little debate. Although the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 established the federal government’s authority to limit the expansion of slavery, no such act had been passed since the ratification of the Constitution.

THE QUESTION FOR CLAY WAS HOW TO GRANT CONGRESS THE LEGITIMACY TO LIMIT THE EXPANSION OF SLAVERY WITHOUT PROMPTING A CIVIL WAR IN THE PROCESS.

Clay remarked that he regarded the existence of slavery as evil. He regretted it and wished that there was not a single slave in the United States. “But it is an evil which, while it affects the States only,

or principally, where it abounds, each State within which it is situated is the exclusive judge of what is best to be done with it, and no other State has a right to interfere in it.” Although Clay abhorred slavery, he understood that in order to avoid the dissolution of the union, he would have to establish precedent that allowed the federal government to legislate toward the “eventual and ultimate extinction of slavery” without extinguishing the union.

The Missouri Compromise was Clay’s attempt to quell threats of secession, but also afford Congress the power to restrict the institution of slavery to the states within which it existed, and eventually strangle it there. In his Peoria Address, Lincoln charged Stephen Douglas with the unconstitutional repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Lincoln was so opposed to Douglas’ “repeal” because he understood that once the precedent set by Clay in the Missouri Compromise was overturned, the federal government would have no authority to restrict slavery, and that with no restrictions on slavery it would become “lawful and just in all territories.” Lincoln understood that the Missouri Compromise not only established the spirit of compromise, but also that it declared that the federal government had the authority to determine the legality of slavery in certain territories of the Union.

JUST AS MADISON HAD DISTINGUISHED FEDERAL AND NATIONAL, CLAY WOULD DISTINGUISH UNION AND NATION.

Clay understood that the nation existed before the Constitution and the Union. The nation, he argued, consisted of a diverse people with “great and powerful principles of cohesion.” The nation, by chance and circumstance alone, provided commonality through origin, language, law, history, and love of liberty. Although the nation provided commonality, it did not bind citizens together through mutual affections, national fraternity, or civic duty—only a latent compact, such as the Constitution, could establish an enduring bond.

But by 1818, the sentiments of nation and place were beginning to run contrary to the dictates of union. Rather than identify as citizens of the United States of America with a vested interest in promoting the general welfare, the states warred for sectional majority in Congress to determine the legitimacy of slavery within territories that hoped to become states.

Through the Missouri Compromise, the tension would come to a head as representatives would settle questions over what tools would safeguard the principles of liberty: would it be popular sovereignty, or did the federal government possess the power to reject the proposed constitutions of territories based upon the question of slavery?

Throughout Clay’s Speakership, his answer to sectional arguments was peaceful constitutional majorities. He understood that representative government through deliberation and choice was only possible through such majorities and through rules that allowed those majorities to debate and determine policy. In fact, Clay was first elected Speaker because it was believed that he could display the leadership needed to foster such debate. In October 1810, upon election to the House, Clay arrived early in Washington, presumably believing that some important action would occur before his first session. When he arrived, he must have been struck that his colleagues were young, many having been born after the signing of the Declaration, but also that they were calling for a caucus to discuss the organization of the House.

They first deliberated about who should hold the speakership. Macon seemed the alternative to Clay, but he was a Republican of the old guard, wary of foreign entanglements, and dedicated to states’ rights—many also believed that he was too friendly with John Randolph, a representative from Virginia who “ran roughshod” over the proceedings of the House. It was eventually decided that Clay was the proper candidate because he possessed the willingness “to meet John Randolph on the floor or on the field, and the Speaker might have to do both.”

Another member of the caucus claimed that John Randolph had to be “bridled, for he disregards all rules.” Before Clay had attended a single session, he was elected Speaker on the first ballot. It turned out that he lived up to his promise to bridle Randolph; one of his first orders of business would be to pass a rule that Randolph could no longer bring his hunting dogs into the chamber during regular business. The two would maintain a candid disdain for one another that later culminated in a duel.

CLAY WOULD SERVE AS SPEAKER FOR THE NEXT TEN YEARS, BUT OVER TIME HIS VISION FOR PEACEFUL MAJORITIES TO UNIFY THE NATION PROVED INADEQUATE AS PARTY COHESION WANED DURING THE WAR OF 1812.

In February 1819, the House took up the question of admitting Alabama and Missouri to the Union. Alabama’s admission came without difficulty, but Missouri’s application almost dissolved the Union. Missouri, if admitted, would be the first slave state completely west of the Mississippi. Moreover, it would upset the balance between free and slave states in Congress.

On February 13th, Representative James Tallmadge of New York offered an amendment to the act that would prohibit further introduction of slaves into Missouri and mandate the emancipation of all slaves subsequently born upon their reaching the age of 25. Tallmadge’s amendment marked the first instance of Congress attempting to outlaw slavery in the territories, and such authority was hotly disputed in the chamber.

Thomas Cobb of Georgia threatened, “If you persist… the Union will be dissolved. You have kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish,” to which Tallmadge responded “Let it come.” Congress adjourned on March 3rd, 1819 without fully settling the Missouri question; throughout the summer months, several petitions were

generated demanding that Congress outlaw slavery in Missouri.

When the 15th Congress convened, northern and southern representatives understood the fragility of the situation, but none understood more than Clay himself. He remarked that “the words, civil war, and disunion, are uttered almost without emotion,” and he told John Quincy Adams that he “had not a doubt that within five years from this time the Union would be divided into three distinct confederacies.” But some hope emerged when Maine separately applied for statehood.

On February 16th 1820, the Senate united the two bills of admission into one and Senator Jesse Thomas of Illinois offered an amendment that prohibited the extension of slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of 36*30’ with the exception of Missouri itself. The House subsequently rejected the Senate compromise, so Clay appointed a joint committee consisting of members of both houses. It was decided that the three bills would be separated and Clay would attempt to pass each individually within the House.

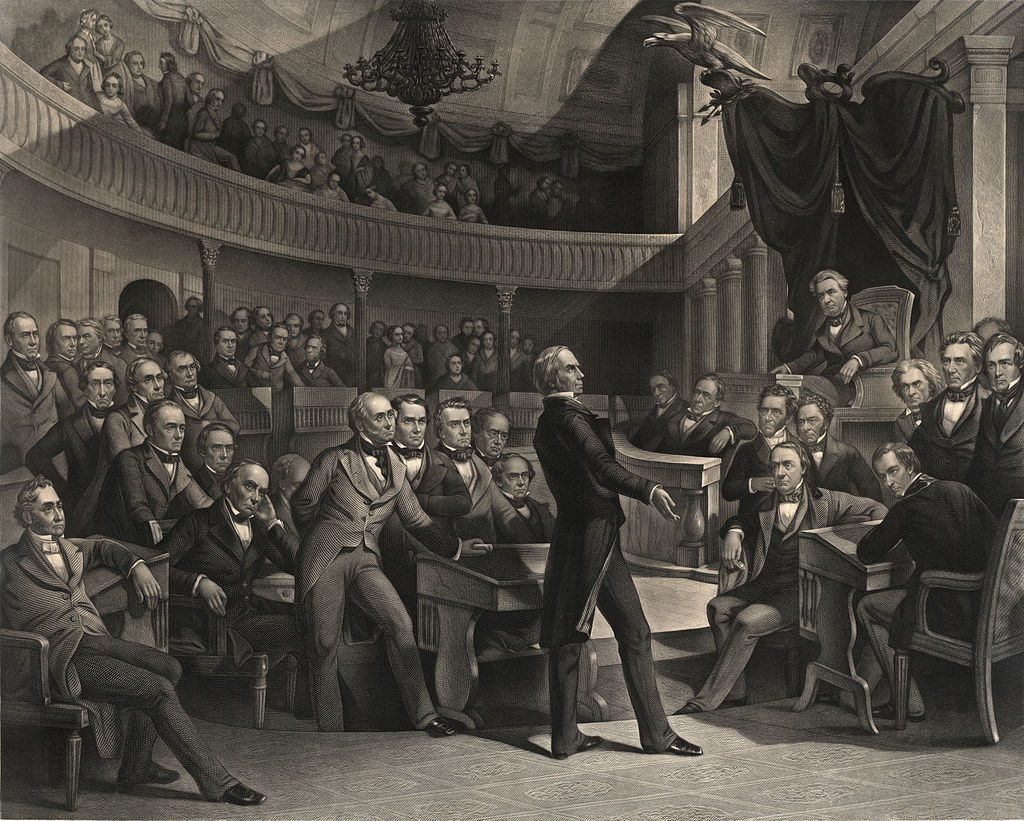

On February 8th, 1820, Clay gave a speech that lasted over four hours attempting to persuade the Northern abolitionists to pass the compromise in order to quell Southern threats of secession. In anticipation of his speech, the House was packed and the Senate adjourned to listen. Although the speech went unrecorded, one account claims that Clay brought his audience to tears as he pleaded for compromise with Pennsylvania’s representatives. Deliberation upon the three bills lasted the entire month of February and on March 2nd, each bill was passed individually.

Clay’s work, however, was not yet done. After the vote, Randolph rose in the House and asked that the vote be reconsidered. Clay announced that it was late and that the motion would be postponed until the following day. The next day Randolph again rose to have the vote reconsidered. Clay ruled him out of order until the routine business had concluded. Meanwhile, Clay signed the Missouri Bill and had the clerk deliver it to the Senate for a vote. When Randolph rose once more, Clay announced that the bill could not be retrieved—the vote was final. On March 6th, President Monroe signed the Missouri bill into law.

Although the Union had been threatened, it was not the commander in chief who played the role of savior: that burden was solely borne by Henry Clay. Not only did his work establish Congressional authority during a time of weak executive rule, but Clay’s role in the passage of the Missouri bill demonstrates an important principle of representative self-government: the principle of majority rule and the Speaker’s role in ensuring that the majority cannot be undermined by the actions of a single representative or a faction.

But most importantly, the limitation of slavery in the Louisiana Territory constitutionalized the Northwest Ordinance and granted the federal government the authority to block the expansion of slavery to all territories in later years.

Samuel Postell is a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Dallas.