John Quincy Adams’ oral argument in the Amistad case is notable for its explicit appeal to the authority of the Declaration of Independence and to the practical political relevance of “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.”

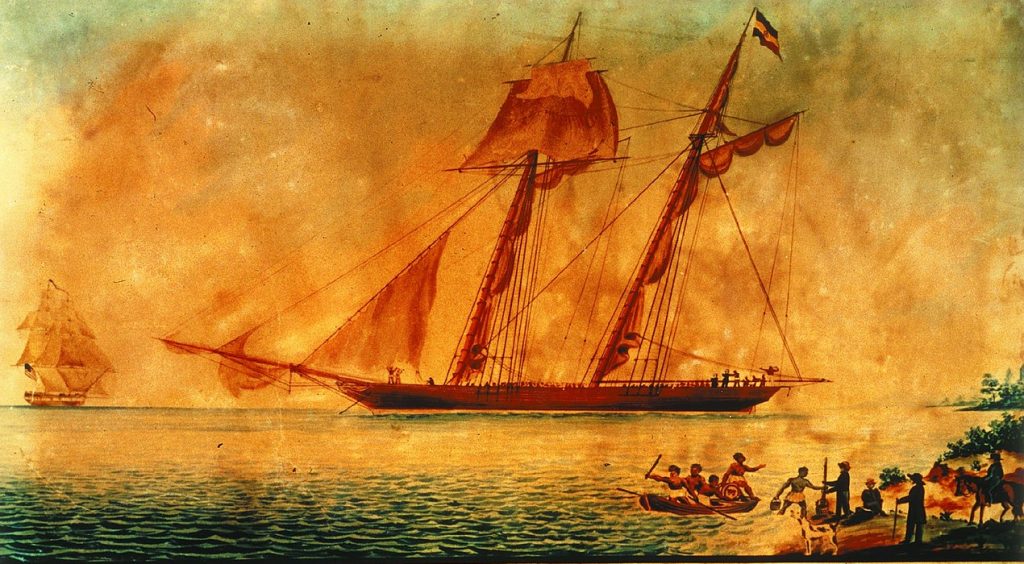

John Quincy Adams – son of the Revolution, former president, and sitting Massachusetts congressman – appeared at the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1841 to plead the case of three dozen Africans who had been found off the coast of New York in command of the Spanish vessel La Amistad. Some two months prior, Spanish slave traders had held the Africans on a short voyage from Havana to Puerto Príncipe; soon the captives overtook the ship, killed the captain, and held two members of the crew hostage. When a U.S. brig intercepted La Amistad off the coast of Long Island, authorities in the courts of admiralty released the Spanish crew members, and took the Africans into U.S. custody.

Spain’s government immediately demanded that the U.S. hand over the Africans—men, women, and children originally from the Mende region of Sierra Leone—en masse, as legitimate property held under a 1795 treaty between the United States and the Kingdom of Spain. The relevant section of the treaty provided for the return of “ships and merchandise” that are “rescued out of the hands of any Pirates or Robbers on the high seas.” Spain’s claim, of course, begged the question: can human beings really at once be considered pirates and merchandise, as robbers accused of stealing . . . themselves? To do so would be to treat them at one moment as morally responsible persons capable of engaging in piracy, and the next moment as mere species of merchandise liable to be returned as the property of another. In their capacity as moral persons, were they owed, at least, separate hearings to determine, on an individual basis, whether they were in fact lawfully enslaved under the applicable positive laws? And as individual persons, could the case be adjudicated, in justice, by treating them in the aggregate as though they were fungible goods and chattel?

Martin Van Buren, as head of the executive branch of the United States government, was initially willing to meet Spain’s demands, a position that prompted Adams to declare before the Court that the president was either ignorant of the “self-evident principles of human rights” appealed to in the Declaration of Independence, or was engaging in “willful and corrupt perjury to his official presidential oath.” Adams deliberately connected the Presidential Oath to the Declaration of Independence, a kind of foreshadowing of Lincoln’s political rhetoric just two decades later in the crisis of the Union. Adams’ oral argument – which stretches over 135 pages in its published form – is indeed notable for its explicit appeal to the authority of the Declaration of Independence and to the practical political relevance of “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” It provides a window into nineteenth-century American political thought, and offers at least one answer to the question of how we should understand the relationship between natural law and natural rights.

NATURAL RIGHTS AND DUTIES ARE IN HARMONY, AND DECIDING WHAT JUSTICE REQUIRES IN ANY PARTICULAR CASE DEMANDS INDIVIDUAL JUDGMENT.

Adams begins by appealing to a classical definition of justice offered by the sixth century Byzantine Emperor Justinian in his Institutes – that justice is the constant and perpetual will to secure to everyone his own right. Several things follow from this definition. Justice, like all virtues in the classical tradition, is a habit that leads to good actions. To be just is to have a constant and perpetual will to do just acts, to render to others what is rightfully their own. As an act guided by will, it is rational and voluntary, rather than sub-rational and involuntary. Justice, then, is rationally scrutable, and it is a virtue unique to rational beings.

Animals, Aristotle reminds us, can emit noises to communicate pain and pleasure, but human beings reason with each other about what is just or unjust. All justice is, in an important sense, social justice. The way we do acts of justice is by rendering to others what is owed to them, what is their own right. Justice, then, entails a relationship between individual duties and individual rights. The objective duty and the subjective right are therefore two sides of the same coin, and the same word can be used to describe both; it is right for me to render to another what is his right. There is no conflict between rights and duties. Adams thus does not take the modern path, cut by Hobbes and others, that begins with individual rights unbounded by morality, leads quickly to a war of all against all, and then prompts men to construct minimal duties designed to maintain peace. Rights, in this sense, are not rights at all, and duties are not duties at all. The theory, Adams insisted, is at its root “utterly incompatible with any theory of human rights, and especially the rights which the Declaration of Independence proclaims as self-evident truths.”

One implication of this otherwise academic discussion is that natural rights and duties are in harmony, and deciding what justice requires in any particular case demands individual judgment. It is a profound miscarriage of justice to subsume individuals into a group when adjudicating individual claims of right. “The Court, therefore, I trust, in deciding this case,” Adams admonished the justices early in his argument, “will form no lumping judgment on these thirty-six individuals, but will act on the consideration that the life and the liberty of every one of them must be determined by his decision for himself alone.” This seems basic enough, but the claim of Spain and the Van Buren Administration (which, Adams insisted, had willfully taken the side of “utter injustice”) was precisely that each individual should not have his day in court. What made this position even more troubling, and tragic, was the outcome of The Antelope, a case decided some fifteen years prior. With a factual record remarkably similar to La Amistad before him, no less a jurist than John Marshall had approved a U.S. circuit court’s decision to treat enslaved Africans as fungible goods to be either freed or divvied up among claimants by a simple lottery system.

IT IS THE DUTY OF A STATESMAN TO BRING SENTIMENT MORE IN LINE WITH JUSTICE, BUT DOING SO REQUIRES THAT ONE PRUDENTIALLY WORKS WITHIN THE PARAMETERS OF PUBLIC OPINION.

Adams’ rhetorical strategy in La Amistad began by drawing out the underlying racial assumptions in the case by juxtaposing the dual claims of reason and sentiment. The actions of the executive branch of the U.S. government, Adams noted, had been motivated from the beginning by sentiment – sympathy with the white, and antipathy toward the black. Justice, however, is rational, a voluntary will to do right by individuals irrespective of sentiment. Yet Adams also recognized that reason needs sentiment as its aid; sympathy and antipathy must be redirected to rightful ends. That sentiments might be malformed and directed to unjust ends points to the possibility of a natural—that is, rational—standard of justice by which we can distinguish between well- and ill-formed sentiment.

It is the duty of a statesman to bring sentiment more in line with justice, but doing so requires that one prudentially works within the parameters of public opinion. For these reasons, Adams appeals explicitly to the Declaration of Independence, a document that teaches well the first principles of justice and is also revered by members of the Court. Pointing to two copies of the Declaration on the wall of the Court’s chambers, “which are ever before” the justices’ eyes, Adams declared: ‘I know of no other law that reaches the case of my clients, but the law of Nature and of Nature’s God on which our fathers placed our own national existence.” The natural law provided the “foundation of all obligatory human laws,” and it was, according to Adams, in fundamental harmony with the principles underlying Anglo-American constitutionalism.

In his concluding remarks, Adams invoked an untranslated verse from Virgil’s Aeneid: “hic caestrus artemque repono.” The line comes from the old boxer Entellus’s post-fight oration, after defeating a young and brazen challenger, and it is translated: “In this place I, the victor, put down my gloves and my training.” Adams, however, edited out the word victor. He did not know if victory lay on the horizon, but he did view himself as an old fighter confronting a new challenge – the positive defense of slavery as something good to be preserved rather than a tragic evil to be lamented, the cornerstone of American democracy rather than the rock upon which it must break. When the dust settled, the case did find its resolution in favor of Adams’ clients, and Joseph Story appealed in his decision both to positive international law and to the “eternal principles of justice.” Adams was, in this sense, the victor, but ultimate victory – if it was to come at all – entailed a fight over principles of natural justice that would extend deep into subsequent generations.

Justin Dyer is the Director of the Kinder Institute and Professor of Political Science at the University of Missouri. He is the co-author (with Micah Watson) of C.S. Lewis on Politics and the Natural Law.